Fracking Versus Science Communication

The word ‘fracking’ has become aligned with unconditional taboo in the United Kingdom in a two year interval. Strong public scepticism has been fuelled by the parade of paraphernalia arriving from the USA...

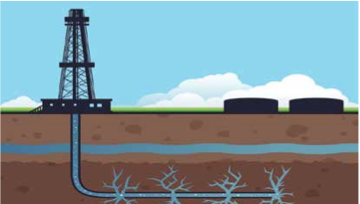

The word ‘fracking’ has become aligned with unconditional taboo in the United Kingdom in a two year interval. Strong public scepticism has been fuelled by the parade of paraphernalia arriving from the USA. Images ranging from flaming taps right through to ominous ‘frack pads’ litter the internet. In the summer of 2013 protestors took to the streets at the G8 Summit in Fermanagh. Balcombe became the focal point in the notorious Cuadrilla row, exhibiting some of the most vitriolic resistance. While there may be fundamental ethical and environmental questions to be addressed in context of the wider fracking debate the sporadic sensationalism of many individuals and parties ought to be condemned. Credence must also be conceded to empirical analyses and research into the practice. It must be highlighted that the process of hydraulic fracturing has been carried out on a number of occasions prior to the 2011 Blackpool ‘Earthquake’. Nodding donkeys (remnant equipment from fracking processes) pepper the fields surrounding the Gainsborough and Beckenham communities. Fracking has been carried out as far back as 1969. It must be noted that controversial ‘shale’ fracking did not take place in this instance. In spite of this, the case study highlights the dangers associated with the selective implementation of statistics employed by certain media outlets. This creates an exploitative smokescreen, especially on internet search engines, thus masking the truth by crowding it in skewed hysteria. Public opinion is confined to a fabricated status quo and the problem becomes a self-exciting perpetuity. The UK debate can be realigned through the clarified efforts of science communication. A 2013 BBC documentary entitled ‘Fracking: The New Energy Rush’ and presented by Professor Iain Stewart of the University of Plymouth demonstrated that the fracking debate, despite the schism in public opinion, contains many other dimensions that could shift the balance of debate to the underlying science. The documentary drew inferences from the USA. States like North Dakota typify exponential growth in the fracking industry. It has provided the country with an unprecedented sense of ‘energy security’ through a liberal supply of domestic gas. It has boosted exports of American coal. The other side of the phenomenon is the myriad of construction, deforestation, increased emissions and noise pollution. The crux of American opposition centres on civilian health within areas of industrial development. Many also question the consequences for the water table, the integrity of agriculture and biodiversity. It is clear that the priorities of the American fracking industry cluster around the economics (Many middle men and landowners have accumulated small fortunes) . The industry has developed without sufficient regulation. One might infer that the physical process of hydraulic fracturing is misconstrued as the evil entity. In actuality it is the supporting framework of policy, business and commercialism that generates the imperfection. The UK could learn from these mistakes. First and foremost, the process of fracking requires exceptionally high pressures to fracture rock. By its very nature it demands diligence, focus and time. A mediated, reduced rate of production from shale fracking could minimise unnecessary damage to surrounding bedrock and reduce the (still vague) environmental hazards. It could unify the disparity between pragmatism and economics by encouraging a more relaxed and (crucially) localised energy market. Secondly, this could engender an ethos of openness surrounding the practice. In the United States many companies champion injunctions, concealing the composition of their fracking fluids. While this is favourable for business in context of an aggressively competitive energy market, it detracts from the integrity of science and health policy. The UK could learn from this. The composition of fracking fluids would need to be disclosed, in line with that of Government expenses and the already established ethos of free information. To conclude, science communication may prove to be the crucial and restorative link in the chain of the future UK energy market. It can serve to show that fracking, while a chief focus, must be considered within a cohesive approach to science, economics and ethics. This may prove to be easier said than done.