Eye eye, what have we here?

Eyes in the back of your head? More likely than you think explains Alexandra Easter

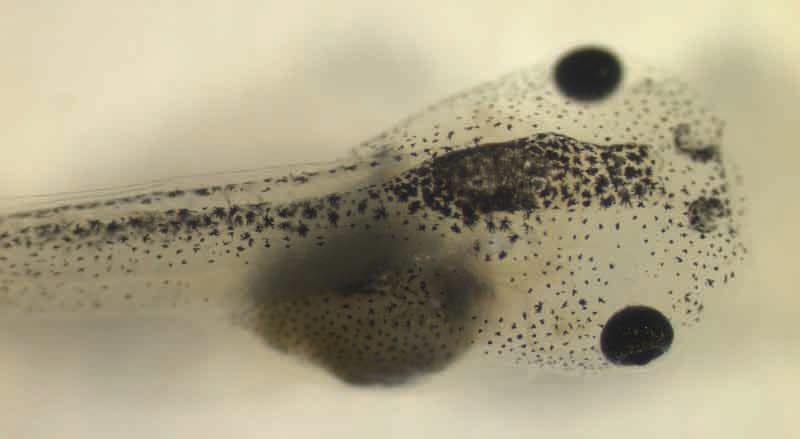

You might think that having eyes in the back of one’s head was a quality reserved only for mothers and teachers, but research published in The Journal of Experimental Biology has shown that it is also possible in tadpoles.

Biologists at Tufts University, Massachusetts, have created tadpoles with ectopic eyes along the length of their bodies by transplantation during early embryonic stages. Importantly, these eyes were shown to be functional in 19% of cases (a small but statistically significant result). Surprisingly, these functional ectopic eyes did not send their information directly to the brain (as the optic nerve does in normal vision) but sent nerves to the spinal cord instead.

Post-transplant tadpoles that made the connection from their new eyes to their spinal cord were able to fulfil a simple light-based learning task. When allowed to swim freely between areas bathed in either blue or red light, and given a small electric shock when they entered the red zone, the tadpoles learnt to avoid the red zone to the same extent as their normal-eyed counterparts.

It is clear that these new insights into the connections between the vertebrate brain and body could propel new research in fields from artificial limbs and regenerative medicine to engineering, computing and beyond.

These results have potential significance in more fields than you might think, from regenerative medicine to engineering and robotics.

The authors have demonstrated a high level of brain plasticity, particularly important in their tadpoles, whose brains must cope with dramatic morphological changes during their lifetimes. The vertebrate brain cannot only interpret visual information no matter what part of the body it comes from and without a direct connection, but co-ordinate behaviour accordingly. From an evolutionary perspective the authors propose that plasticity of the brain, rather than hardwiring, allowed the animal to become more complex without compromising its own fitness.

A more abstract parallel is drawn with robotics and computing: could this research be relevant to the development of networks that can adapt to change or damage? Or alternatively, can we learn from current methods in data processing to figure out just how electrical signals coming from the body of an animal can still confer visual information? For example, when a signal is sent, it contains a ‘header’, which indicates where it came from and what type of information it encodes.

It is clear that these new insights into the connections between the vertebrate brain and body could propel new research in fields from artificial limbs and regenerative medicine to engineering, computing and beyond.

DOI: 10.1242/jeb.074963