Underground networking

Sarah Byrne explores a potentially useful facet in plant-fungi relationships

You probably think humans invented communication networks. However according to recent research, plants might have got there first, communicating with each other through extensive underground fungal networks.

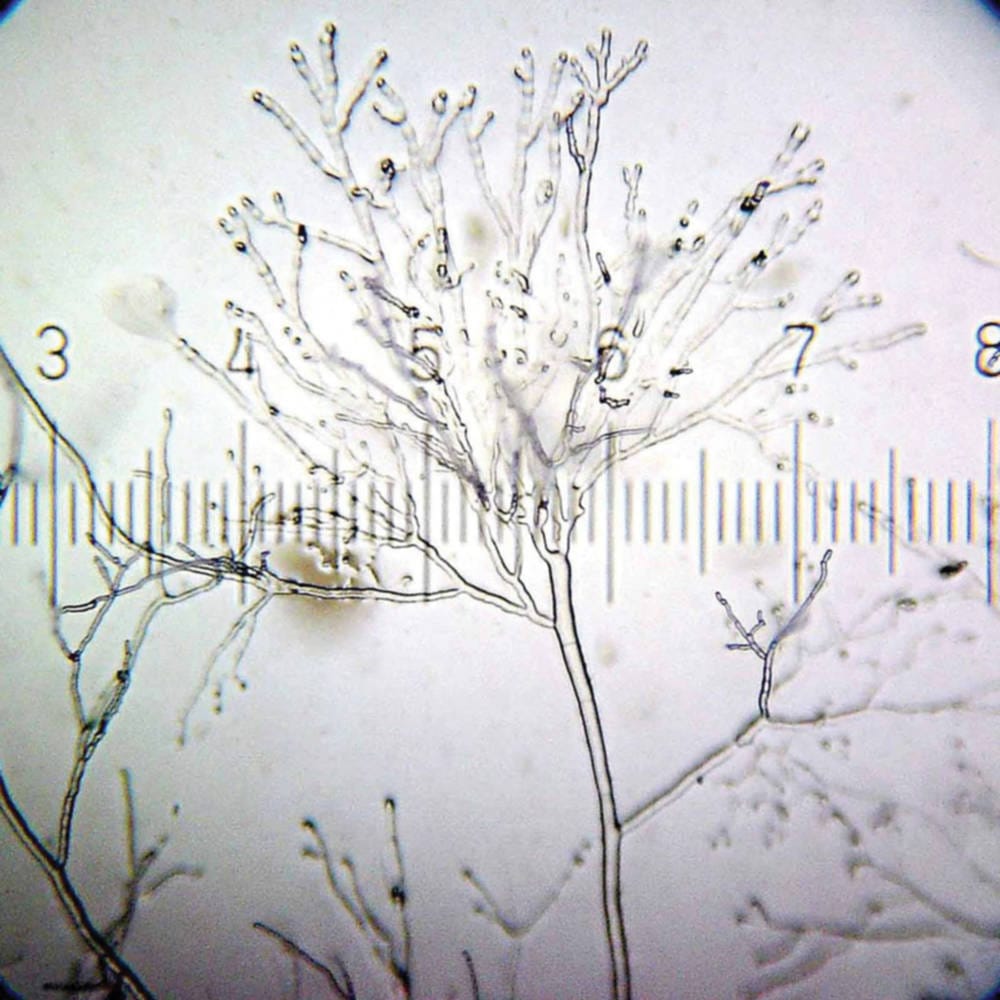

Most soil-based fungi grow as hyphae: long, branching fibres that form spreading network-like structures known as mycelium. In some cases the fungus goes a step further, interacting with the roots of a plant beneath the ground, in a symbiotic or mutualistic relationship. The mycelium is highly efficient at absorbing water and minerals from the soil, and the colonised plant gets the benefit of this, allowing plants to thrive even in drought conditions or mineral-poor soils. In return, the fungus feeds off the energy-rich sugars made and stored by the plant. The mutualistic relationship may also increase the plant’s resistance to disease and toxic metals.

It has been suspected in recent years that fungal connections between plants might play some role in communicating. The recent study, however, provides the first experimental evidence of this mechanism in action.

A new way to protect agricultural crops against pests and disease?

The bean plants used in the study can develop resistance to infestation by aphids when exposed to a sample of the insects. However when two plants were connected by the fungal network, the aphid-exposed ‘donor’ plant was able to transfer signalling molecules through the mycelial network to a ‘receiver’. This gave the receiver plant the information it needed to develop aphid resistance, despite never having encountered the aphids itself. A fine mesh barrier was used to prevent actual root-to-root interactions, and controls using non-connected plants demonstrated that the communication was not simply diffusion through the soil, providing strong evidence that the plants really are chatting to one another over the network.

The researchers suggest that we may be able to manipulate mycelial networks to develop new ways to protect agricultural crops against pests and disease. Either way it is clear that these generally overlooked networks are a huge part of plant ecosystems, maybe as much so as the internet and social networks are a part of our society.

DOI : 10.1111/ele.12115