Curiosity celebrates one year of Martian exploration

Marion Ferrat takes a look at Curiosity’s first year on the Red Planet

Just over a year ago, on 6 August 2012 (5 August Eastern Standard Time), a little something called Curiosity made its final descent towards the Martian surface. Curiosity had spent over seven months making the journey from Cape Canaveral in Florida to the outer atmosphere of Mars. After a series of perfectly executed moves, and an excruciating wait for the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) team at NASA, the rover landed safely in Gale crater, near the Martian equator.

A short history of Mars exploration

Curiosity is not the first rover NASA has sent to the red planet. Two Viking robots landed in 1976 and Mars Pathfinder safely delivered the solar-panelled Sojourner rover in 1997, which explored Mars for 83 Martian days (just under three months here on Earth). Curiosity’s cousins Spirit and Opportunity arrived on Mars in 2004 in search of clues that water had once flowed at its surface. The two rovers have provided NASA and the world with some amazing insights into the Martian environment. They captured striking images of geological structures and revealed the presence of minerals such as hematite and goethite, which on Earth are associated with water-rich environments. Spirit and Opportunity didn’t just focus on what was under their wheels. They also looked up and carefully monitored changes in the Martian atmosphere, measuring variations in temperature and capturing images of dust devils and clouds.

What is Curiosity looking for?

The question at the centre of the Curiosity mission is this one: Did Mars ever have the right environment to support microbial life? To try and find answers, the rover has been looking at the geological, physical and chemical characteristics of the planet’s surface.

But Mars is a big place... so where to start? The MSL scientists had to think very carefully about which location would give them the best chance of revealing the true past environment of Mars and its ability to host microbial life forms.

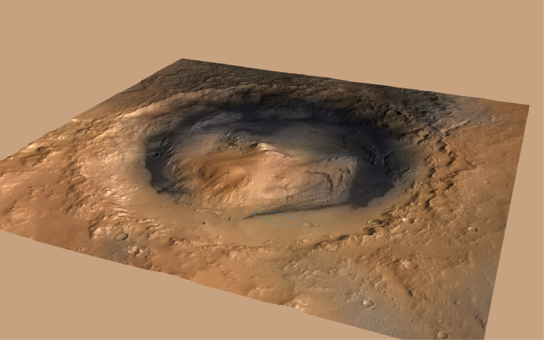

The team chose Gale crater. 154 km in diameter, the crater is the remnant of a very old impact that occurred over 3 billion years ago, towards the end of tumultuous chapter in the history of the solar system called the Late Heavy Bombardment, when stray asteroids and comets were pummelling the inner solar system.

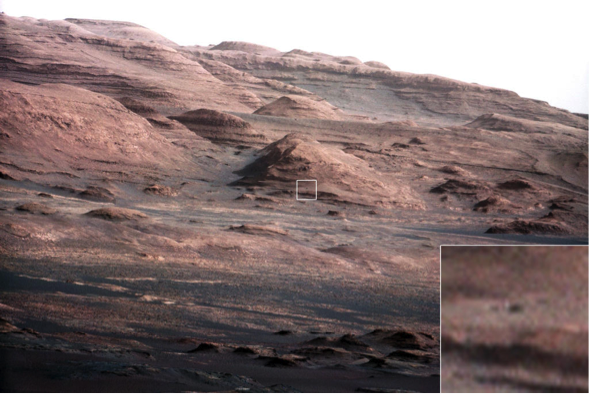

Gale crater was chosen because of its unique structure. From its centre soars Aeolis Mons, or Mount Sharp, a 3 mile-high mountain. Between the mountain and the rims of the crater lie a series of relatively flat plains. One of these, Aeolis Palus, is where Curiosity touched base.

Mt. Sharp is fascinating because it contains the thickest pile of sediments yet identified on Mars. The base of the mountain is of particular interest as it records a very long history of erosion and deposition from the rocks on this towering mountain. Sediments on Mars, as on Earth, accumulate over time from small particles of rock eroded and displaced from the top of mountains by physical or chemical processes linked to climatic conditions. The thick sediments of Mt Sharp therefore represent a direct view into the processes that have occurred on Mars over a huge amount of time.

So what is it about Curiosity that makes it so special?

Curiosity is no common rover. It is one thousand times heavier than Sojourner and is equipped with the most advanced tools available for drilling and analysing rocky Martian samples. Curiosity can drill holes, collect rock powders and analyse them in its very own in-built laboratory. This personal laboratory contains 10 state-of-the art instruments capable of looking at the mineralogy and chemical composition of the drilled samples, the composition of the atmosphere, background radiation and other aspects of Mars’ environment, which are crucial for understanding the planet and preparing for future unmanned and manned missions. Not only are scientists receiving images of rocks that could represent an ancient water-rich environment, they are able to test these hypotheses directly in the field.

What has kept Curiosity busy in its first year?

The rover has driven over one kilometre from its landing site in Aeolis Palus, slowly and carefully investigating its surroundings along the way.

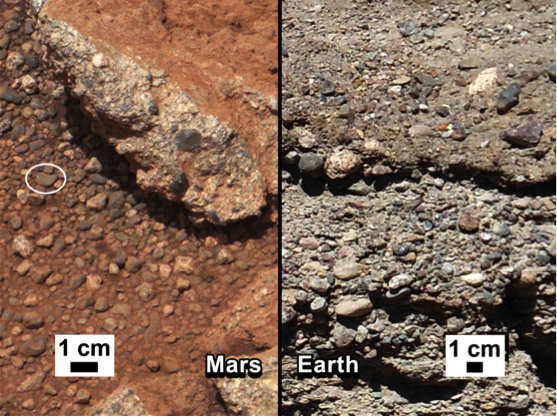

Curiosity immediately identified some exciting rocks. On Earth, rocks that form in water-rich environments such as rivers or lakes have very particular features that are instantly recognisable to geologists. Rivers, for example, can transport relatively big pebbles over large distances. As the rocks are displaced by the flowing water, they collide and little by little, chip off each other’s sharp edges, rounding them off until they acquire their smooth pebble shape. The pebbles eventually slow down and settle in the surrounding sediment, forming a particular type of rock that geologists call a conglomerate.

These types of conglomerates are exactly what Curiosity found within the first few weeks of its mission. The rocks are striking for their resemblance to our own terrestrial riverbeds. They are the first to show that the water that once flowed here must have been ankle deep, and quite vigorous.

Curiosity then carried out its first drilling operation in an area called Yellowknife Bay. The formations the scientists could spot there showed promising signs of ancient habitable environments, so Curiosity was sent off to investigate.

The first drill was a striking success. As the rover recovered the powder samples, Mars’ soil turned from red to grey. Colour can provide important information in geology, as the colour of a rock is often linked to the chemical state of its constituents, and therefore its environment. Iron, an element very common in all rocks on Earth, changes colour depending on the surrounding environment. A common example of this is iron rusting and changing from grey to red in the presence of oxygen.

Curiosity showed just that. The iron in Mars’ rocks went from rusty red to pale grey as the rover dug under the surface. The grey colour represents a form of iron that is important for microbial metabolism; a second clue to a habitable Martian environment. The analyses of these powders also revealed key chemical ingredients important for life, as well as the presence of clay minerals, more indications of a past water-rich environment.

All of these results point to one conclusion: the possibility of an ancient habitable environment on Mars. Prof. Sanjeev Gupta from the department of Earth Sciences and Engineering, Imperial College London, is one of the Curiosity science team members. He has explained that the morphology, mineralogy and chemistry of the rocks found by Curiosity don’t just indicate that there was water, they also show that this was sweet water, neither too salty nor too acidic, just right for life to thrive in. If life ever existed on the surface of Mars, these are exactly the types of environments in which we might find it.

Curiosity is now back on the road to Mount Sharp. Along the way, the rover will keep looking for signs of Mars’ past environment, taking photographs of its surroundings, drilling samples, analysing them to determine their mineral and chemical compositions and studying the base of the Martian atmosphere. It will also set the scene for the work of Curiosity’s airborne sibling, MAVEN, who is due to leave Earth in November 2013 on its very own journey to the red planet. MAVEN will study Mars from the top down, trying to understand what caused its atmosphere to have been lost to space. Let’s wish these incredible adventurers, and the hundreds of scientist and engineers behind them, the best of luck. Who knows what they may find on their way, and what they could reveal about our universe?