A trip down memory lane

Utsav Radia on why and when you stop remembering your early years

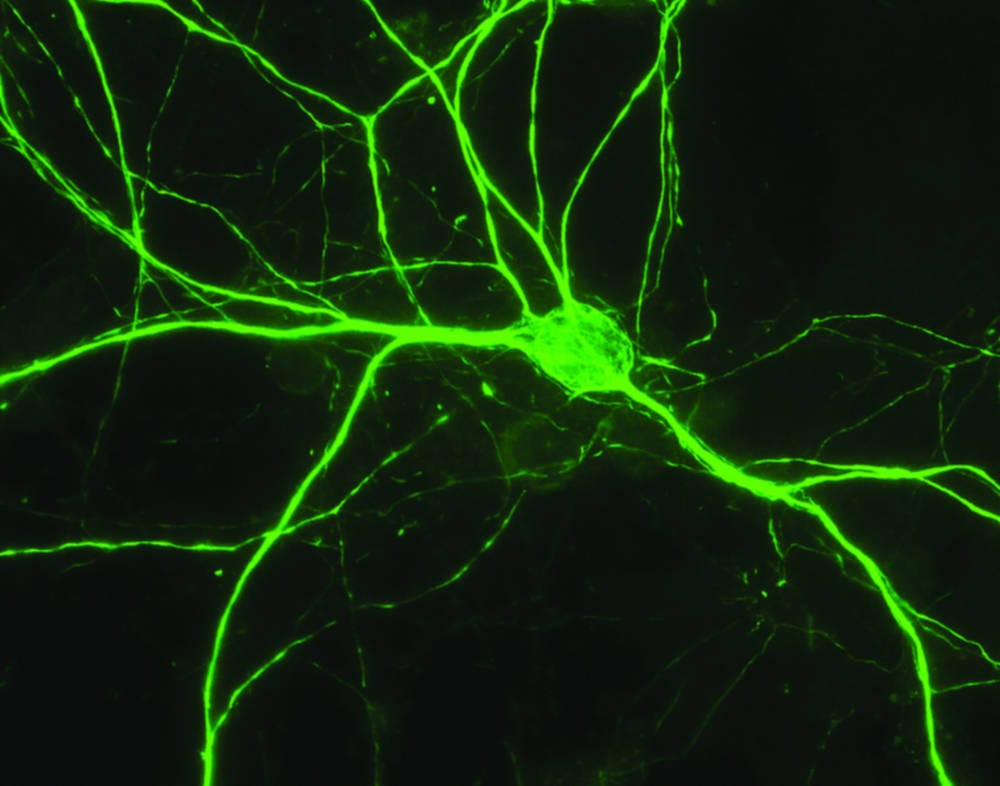

Have you ever wondered why we tend to remember some things more than others? Our nervous system is a highly organised, complex system of neurones (units that communicate via electrical signals), their dendrites (highly branched outgrowths) and support cells called glia (involved in processes such as maintenance and protection). It is estimated that the human brain contains around 86.1 billion neurones, with some capable of having up to 400,000 dendrites.

In the developing embryo, undifferentiated precursor cells develop to form the neurones and glia. What is fascinating about these processes is what follows the differentiation phase: up to 50-70% of neurones can undergo programmed self-destruction – apoptosis. This concept of neurones being remodelled and constantly forming new synaptic connections is known as synaptic plasticity – it is speculated that this occurs to fine-tune the connectivity in the nervous system.

This process is believed to slow down immediately after birth (and then on throughout life) and is supposed to be crucially important for memory development in infants. Children use their memories to learn new information; however, very few adults can recall events that occurred before the age of three. Sigmund Freud coined the term “childhood amnesia” to describe this observed loss of recall of events in the infant years.

An experiment run by a team of psychologists at the Emory University, led by Professor Patricia Bauer, documented early autobiographical memory formation in children (starting at the age of three and then successive years) to determine the age at which these events were forgotten. Their findings, published in the journal Memory, show that children between ages of five and seven could recall more than 60% of early-life events, whereas children who were eight to nine years old remembered less than 40% of early-life events.

Interestingly, they also found that although children aged five to six could remember a greater percentage of early-life events, their narratives were less complete. However, older children – despite remembering fewer events – were able to describe the events they did remember in more detail. Several possible explanations have been put forward to explain this observation, such as improved language skills and reinforcing of synaptic connections with each subsequent recollection of these memories.

The analogy used by Professor Bauer was that of pasta draining in a colander: “Memories are like orzo [rice-sized pasta]... as the water rushes out, so do many of the grains of orzo” whereas adults use a “fine net instead of a colander” to retain many of their memories.

Although we may be closer to knowing the changes that occur between early childhood and adult memories, the precise timing of this change is yet unknown. Professor Bauer ended her interview by saying, “We’d like to know more about when we trade in our colanders for a net.”

DOI: 10.1080/09658211.2013.854806