Do you want brains with that?

Anand Jagatia takes a look at prions, the bad behaving proteins

Prions (rhymes with “neons”) are really interesting proteins. They can also be very dangerous. The name is a derivative of the words “PROtein” and “INfectious”, and as the etymology suggests, they cause a group of infectious illnesses, called “transmissible spongiform encephalopathies” (TSEs).

Encephalopathies are diseases of the brain, and spongiform comes from the fact that over time, tiny holes appear throughout the cortex of the victim – just like you’d see in a sponge.

Prion diseases are degenerative and always fatal. Probably the most famous example is the bovine variant, BSE, or “mad cow disease”. The UK epidemic of the disease, which began in 1986 and led to a ten year ban on the selling of British beef, was the result of feeding cattle the mashed remains of other slaughtered animals (including bones, brains and spinal cords). The feeding practices led to the spread of prions from infected to healthy animals and accelerated transmission of the disease.

Human forms of TSE come in several varieties. In rare cases, mutations of the gene for prion protein may cause disease, but the majority of the time it is exposure to infectious prions is to blame. “Kuru”, a disease endemic to tribal areas of Papua New Guinea, is probably the condition with the most gruesome history – it is believed that the spread of the disease among the Fore tribe was due to the cannabilistic funeral rights practised by its members. The incidence of infection was found to be much higher in women and children, who were generally given the less desirable body parts to eat, including the brain, where most of the prion matter is concentrated.

Misfolded prions are also extremely stable and can’t be destroyed by heat, so cooking meat doesn’t prevent infection. Despite claims of the UK government during the BSE crisis that infected beef was completely safe to eat, there have been 175 reported cases of the human form of the disease in the UK since the ban. Most of these cases are thought to be linked to consumption of beef infected with prions.

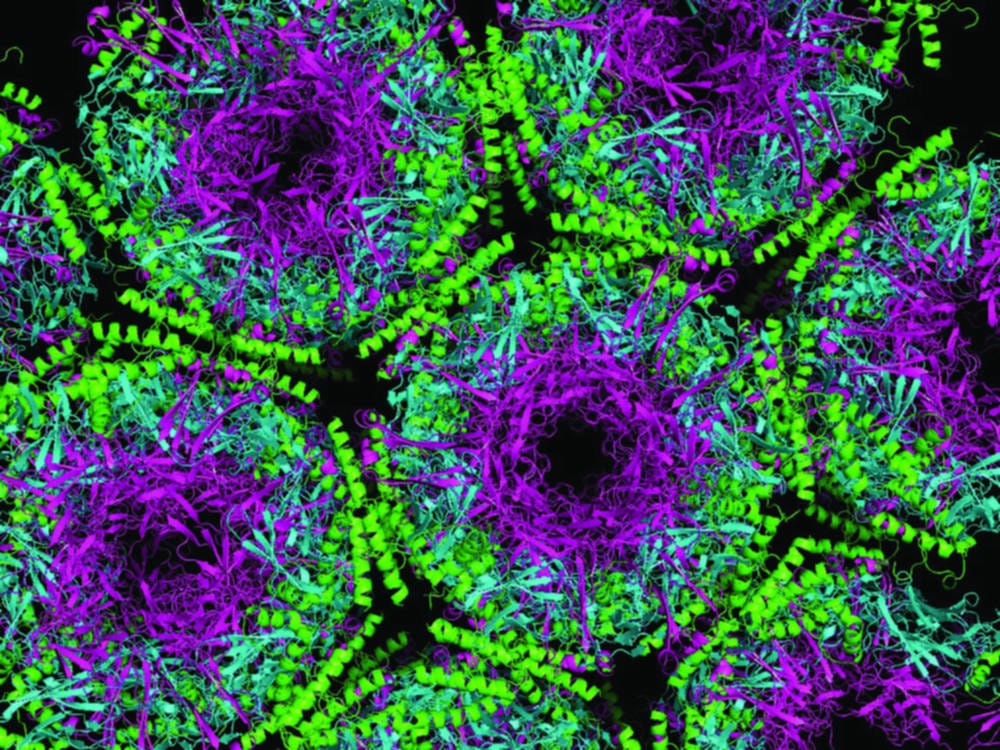

Scientifically, the puzzling thing about prions is the way they replicate. Not all prions are infectious – the normal kind is found in many cells throughout the body, especially the cell membranes of neurons. But prions can also exist in a misfolded state, and this is the kind that leads to disease.

According to the popular scientific view, infectious prions can act as a scaffold for normal prions to misfold themselves, and this chain reaction causes the infection to spread throughout the brain.

Once misfolded prions are formed, they clump together in big chains called amyloid fibres, which are toxic to cells and cause them to die. The prion hypothesis is still controversial, because all other infectious agents, (like viruses) need RNA or DNA to replicate themselves, but it does seem that prions can be infectious without containing any genetic material.

To date, there has been little headway in explaining how all this might happen. Recently though, scientists from the Prion Biology Laboratory in Italy have made promising progress. Last week, the group published a paper in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, outlining how they used small proteins, called nanobodies, to stabilise misfolded prions and then used X-rays to explore their structure.

For the first time, their research sheds some light onto the early stages in the mechanism of prion misfolding, which might be the first steps to understanding how these peculiar proteins are so deadly.