Shifting attitudes towards MDMA

Lauren Ratcliffe reports on the medical side of the popular clubbing drug

MDMA, or for you chemists out there 3,4-methylenedioxmethamphetamne, more recognisably referred to as ecstasy is a prevalent and well-known drug. It’s no state secret that a majority of people who are reading this have encountered it - whether that be through occasional to regular recreational use or simply knowing someone who has taken it.

In the 2013 Felix drug survey, MDMA was revealed as the second most regularly used illegal drug amongst students at Imperial, closely following Cannabis. Furthermore, according to a recent drug survey by The Guardian, 31% of the UK population aged between 16-24 have taken illegal drugs and 25%of this subsample admitted to having taken MDMA at least once in their lives. It is therefore safe to say it is a promiscuous drug, whose usage has been shown to span across all ages and social classes. Regarded amongst scientists as an ‘empathogen’ encouraging social interaction and openness. But better known by clubbers for its ability to make you feel like you’ve just eaten a golden mushroom in Super Mario. Making your heart race, booty shake and sweat pour as it fuels an all-night dance workout of the like you would never see at Ethos.

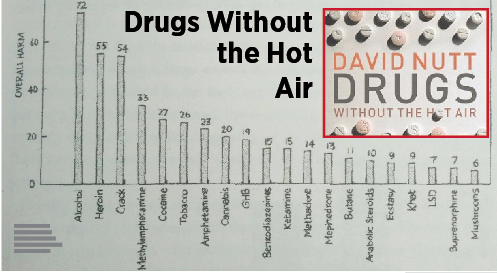

Researchers at Imperial are taking a different perspective of MDMA and shifting attitudes away from its widely renown clubbing reputation and moving them towards its medical potential. Dr Robin Carhart-Harris (you may have read my article a few weeks ago about his research with LSD), alongside other researchers at Imperial College and University College London, including the infamous Prof David Nutt, are utilising MDMA’s empathy-inducing and positive emotion-enhancing qualities with the potential for use amongst patients during therapy to help sufferers of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This team of scientists screened nineteen volunteers on fMRI scanners after taking small doses of the drug (100mg MDMA-HCl) to detect changes in cerebral blood flow (which has been causally linked to neurological activity). They also conducted memory cues describing participants’ favourite and worst autobiographic memories to see their reaction on MDMA compared with controls.

Volunteers rated their favourite memories as significantly more vivid, emotionally intense and positive after MDMA than placebo and experienced worst autobiographical memories as significantly less negative, alongside a reported reduced fear-response. One participant of the study described their experience: “When I reached back for the bad memories [under MDMA] they did not seem as bad; In fact, I saw them as fatalistic necessities for the occurrence of later good events.” With a marked positive shift in emotional perception of both favourite and worst autobiographical memories the results of this particular study indicate that MDMA holds potential for use in conjunction with psychotherapy. After looking over scans of the volunteers’ brains, they also saw that in participants that had taken MDMA there was increased blood flow to an area of the brain known to be involved in processing complex visual stimuli, such as faces. They therefore hypothesised that this increased activity related to the reports of heightened vividness of memory recollection while on the drug.

Exposure therapy is the current treatment for PTSD and is very effective. It requires patients to remember traumatic memories in order to re-engage and overcome them (similar to treatments for phobias). One theory for using MDMA alongside exposure therapy is that it could allow the patient to more easily engage with traumatic memories, making psychotherapy more effective and also shorten the costly treatment procedure.

As with almost everything in science, the results from this study should be taken with a pinch of salt and with the limitations of the methodology in mind. Despite an improved sample size compared with previous research, it is still small and there is always room for expansion with these studies, which is partly the reason why they are carried out in the first place. Dr Robin Carhart-Harris also stressed the need for more research into further understanding of exactly how MDMA has such a potent and influential effects on emotional processing.

Last week I held an interview with Dr Robin Carhart-Harris about his career and research into LSD. A charming man and interesting speaker, don’t miss you - keep your eyes pealed for his feature article in a future Felix edition.

Doi:10.1017/S1461145713001405