The race to find a cure for ebola

What still needs to be overcome to find a cure?

The Ebola outbreak has claimed about 4,900 lives to date mostly in the poverty-stricken countries in West Africa — Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea. As the death toll and number of cases rise exponentially, scientists are scrambling to develop treatments that would stop this epidemic, which Oxfam describes as a “humanitarian disaster”. Until there are vaccines approved by the FDA, standard public health containment measures will be used to control the situation.

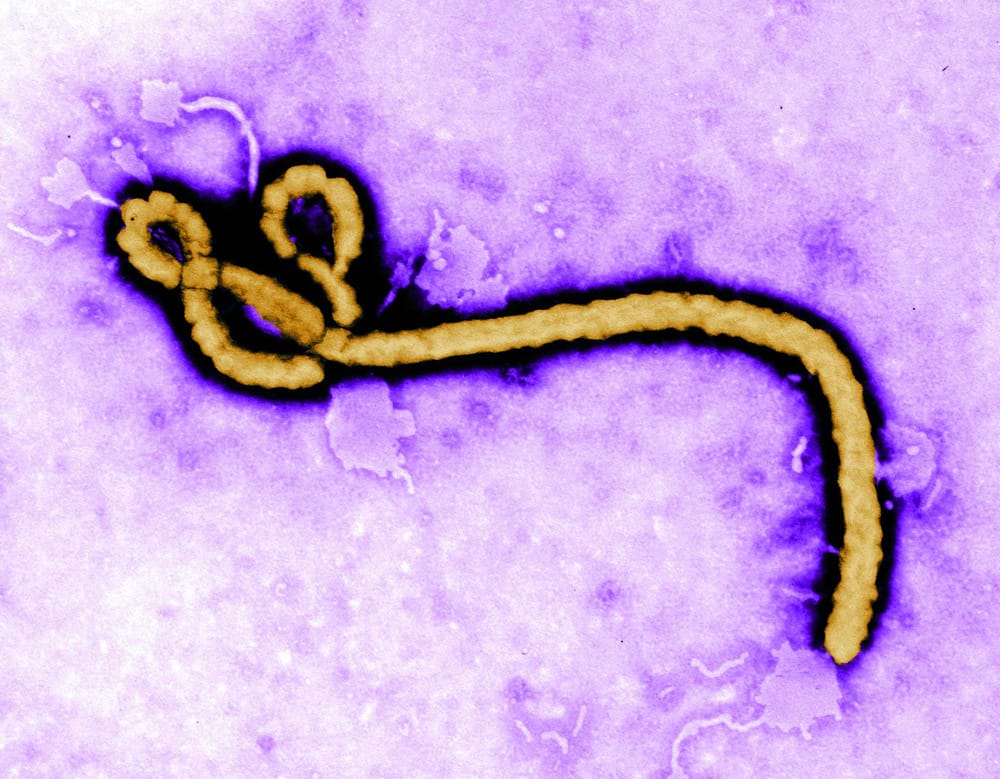

The ebolavirus is particularly adept at evading our immune system, and among the proteins which play a role in it are VP35 and VP24. The first assembles into a dimer and then coats the RNA backbone of the virus to prevent detection by the immune system. The second blocks the cellular production of interferons, molecules which signal the presence of the virus. The receptor site of the virus remain hidden beneath its glycoprotein branches, also to avoid recognition, until the branches attach to the host cell and allow the virus’ penetration and entry. Another characteristic in its favour is the filament-like structure of ebolavirus particles which gives it a large surface area to attack many cells.

The virus starts by infecting the leukocytes, then nearly all other cell types, which leads to death less than 16 days after the onset of the disease. The first symptoms include fever and headache, followed by severe stomach pains, sore throats and bloody diarrhoea as the virus multiplies. The infected cells then attach to the vessels and arteries, weakening them and resulting in haemorrhage.

In hopes of sparing more Africans from this unbearable pain, a massive research effort has begun to discover ways to defeat the ebolavirus. A vaccine known as ChAd3 is a chimpanzee cold virus vector incorporated with ebolavirus gene segments. Along with another vaccine called VSV, it was observed to give durable immunity and both vaccines are currently undergoing clinical trials.

Recently, the Wyss Institute of Harvard University announced their ongoing work on a biospleen device which may (or may not) obviate the need for vaccines. The device acts rather like a spleen, filtering viruses from the blood using a magnet. This has brought hope for the treatment of Ebola, but its development and testing would take months or years.

There is also the possibility of the ebolavirus mutating to become more virulent or infective, in which case it would outrace the current efforts of targeting the current virus strain.

Now we can only hope that treatments will be available soon, and that the ebolavirus will not become too prolific until the situation gets out of control. All this shows us the paradoxical nature of viruses, which are such simple organisms yet so difficult to control.