Will the Labour-Conservative duopoly break?

Samuel Bodansky discusses the theory behing political economic modelling

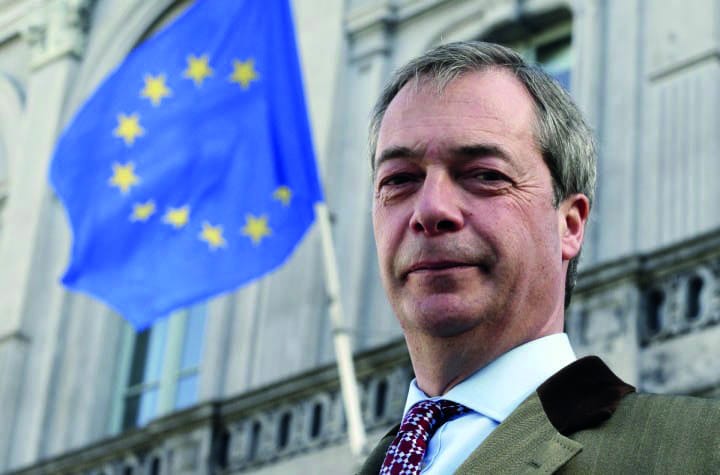

One of the most common complaints in politics is that all political parties seem the same. Douglas Carswell has profited from the rise of UKIP by switching alliances from the Conservatives, claiming that the far-right political party supports “fundamental change” in British politics. However, the fact is that extreme political parties have not fared too well in Britain.

Surely, if UKIP and other parties of the far-Right could really succeed in the UK, then similar parties would have made also made it into government. Nonetheless, since 1945 there have been only two parties in Downing Street, with only Conservative and Labour (apart from other parties within coalitions) holding the majority. Both of these parties are moderate, with the Conservatives on the Right and Labour on the Left. One possible way of answering this question is through the tool of political economic theory and modelling.

In order to model in economics, it is often necessary to make assumptions. For example, an economist might assume that all individuals have perfect knowledge of the market. Assumptions help economists to model real-world systems by simplifying a problem until it can be analysed mathematically.

A useful model was invented by Duncan Black of the University of Glasgow in 1948, known as the Median Voter Theorem. This theorem states that the elected party will have a political view most similar to the view of the median voter; that is, the median individual in terms of political views in the electorate.

The first assumption in the model is that all the parties running in the election can be placed along a single spectrum from extreme Left to extreme Right. This assumption is not always true, as parties have various policies that overlap in terms of political alignment. In the case of the Liberal Democrats, no one really has any idea at all.

Another assumption is single-peaked political preferences. This means that a voter will choose the political party that is closest to their view on the political spectrum. This assumption is also prone to issues; we have seen the far-Right UKIP taking away votes from Labour and Conservative voters in the 2014 European elections.

Sometimes, one particular policy will cause voters to move from the centre to the wings. Voters also tend to get disillusioned with one party and want change; voters can be fickle and swing their votes.

The median voter theorem has important implications: when voter turnout increased in lower-income classes in 1960s USA, the Democrat party-who are supportive of wealth redistribution-performed more strongly in elections. Perhaps a “Yes” vote in the Scottish Referendum would have changed the position of the hypothetical “Median Voter”, taking Labour votes and increasing the power of UKIP, despite their relatively extreme standpoint.

Currently the results of the 2015 General Election are uncertain; it could be the first time that the traditional Labour-Conservative duopoly is broken. Whatever the result, economic models remain a useful predictor of voting behaviour.