An Imperfect Reflection Of Our Modern Society

Fred Fyles takes a glance at the new MIRRORCITY exhibition

To say that J. G. Ballard was only a writer is to do him a disservice. The late British modernist, whose oeuvre included novels, essays, and short fiction, was more of a prophet than an author: seemingly predicting the brutal modernisation that would descend upon the UK during the second half of the 20th Century, as well as the accompanying social stagnation it would bring. Ballard has the honor of having his name as an adjective: Ballardian, which Collins English Dictionary describes as “dystopian modernity, bleak man-made landscapes, and the psychological effects of technological progress”.

You could easily be forgiven if you think this sounds familiar. With the advent of social media, online communication, and mass media, society has moved into an unprecedented age: post-post-modern and more futuristic than the future, the world we now inhabit has been cleft in half: we have the ‘true reality’, and the virtual ‘mirrorworld’. At least, this is what the Hayward Gallery hopes to prove with the opening of its latest exhibition MIRRORCITY. Taking on innumerable big themes – reality, narrative, physical spaces, illusions, social mobility, capitalism, and more – MIRRORCITY is an exhibition that aims high, but never quite delivers such lofty heights, creating an experience that is beguiling, sometimes uplifting, but ultimately frustrating.

Upon entering the bleak cement exhibition space, we are confronted with the vast upturned hull of a ship. Its figurehead lies, pathetic, on the floor: a young woman whose face is shrouded, entangled in the arms of a sea monster. This is the work of Lindsay Seers, whose installation confronts the disconnect between myth and reality. Drawing on the personal story of her great-great-uncle – a sailor – Seers uses film and sound to subtly make the viewer question the world around them.

This theme of artifice is further expounded upon by Turner Prize winner Laure Prouvost, whose work The Artist comprises of a pre-arranged ‘studio’, purportedly that of her conceptual artist grandfather. Squeezing into this cramped space under the beady eye of a security guard, one is immediately assaulted, both visually and audibly: every nook and cranny of the room is filled up with clutter, tools, and ephemera, through which Provost reconstructs the legend of her grandfather. Video installations play throughout the room, while looped soundtracks filter in and out of the space. Urging you to ‘Look here!’ and ‘Look over there!’, they combine to create an unsettling experience.

Another narrative is constructed by Ursula Mayer: taking inspiration from Euripides’ Greek tragedy Medea, she casts LGBT activist JD Samson as both Medea and Jason, creating a ‘post-gender speculation’. A vision of a future where social structures have been broken down, it is at once both inspiring and dystopian. Set predominantly among valleys and deserts, the collage of text, sound, and film is like a Middle Eastern version of Derek Jarman’s The Last of England.

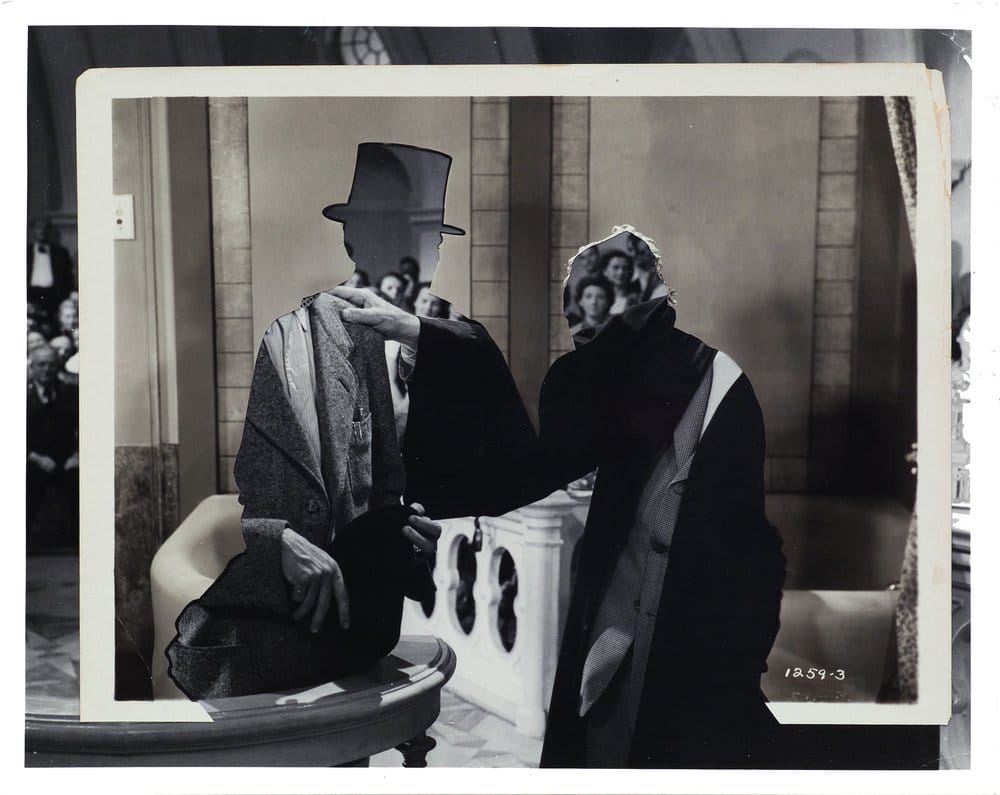

Elsewhere, artists explore the meaning of different media and materials. John Stezaker’s work is excellent as usual, with his repurposed film stills, clipped and pasted together, creating a new visual language. Less effective are Daniel Sinsel’s canvases: aiming to deconstruct the relationship between materials and the feelings they evoke, Sinsel uses extreme juxtaposition to bring out their qualities, but ultimately lacks emotional force.

The exhibtion is beguiling, uplifting, but ultimately frustrating

Helen Marten attempts to do something similar with her rag-tag collection of curios, assembled as if by a magpie. Sadly, randomly throwing together disparate objects does not effective art make – perhaps she should leave it to the actual birds.

The promised exploration of capitalism is fulfilled by Tim Etchells; his fantasy headlines, printed on large sheets, satirise the news of today. Dryer than a gin martini, and packing twice the punch, they take on all manner of topics, from CCTV to gang culture (Sample headline: Tonight’s Presentation: Black Hole – No Intermission). In terms of understanding modern culture, Etchells is way above any other artists in the exhibition; if _Private Eye _is looking for a new contributor, perhaps they should give him a call.

Pil & Galia Kollektiv continue in this vein, with their sculpture _Concrete Gown for Immaterial Flows _taking its name from a Zionist paean to cement. Inspired by capitalism, it is a stage constructed out of concrete blocks which form bar graphs and pie charts, while behind a red arrow crashes towards the earth. The work subverts the argument that capitalism is a natural extension of evolution, instead revealing it as something artificial, manmade, and callous. While the work is quite clever, some of the points the artists are trying to make can at times feel like a bit of a stretch – you’re more likely to see this piece on Top of the Pops than at an Occupy rally.

A highlight of the exhibition is Katrina Palmer, whose emotive soundscape Reality Flickers is housed in an empty locker, a space that “contains nothing but its own absence”. A voiceover that describes the story of Miss Ficker, a naive collector of tossed objects, defined by the fact that they are ‘lost rather than found’, who meets the Heart Beast. Underscored by a subtle, melancholic piano score & unintelligible voices which mutter and stutter, Palmer has created an oasis of solitude and isolation within the middle of the gallery.

John Stezaker's work is excellent, creating a new visual language

The remainder of the exhibition – and trust me, it is extensive – is by and large uninspiring. There’s Anne Mardy, whose constructed spaces are as bland as the cement blocks inhabiting them; Michael Dean’s sculptures, which are dull both in form and name; and Mohammed Qasim Ashfaq, whose work simultaneously demands ‘viewer engagement’ (his words, not mine) and manages to be monumentally insipid. Some work comes from a clear germ of inspiration, such as Susan Hiller’s collage of space sounds and frequencies, but ultimately fails to say anything of importance.

We have seen in the past few years that the Hayward Gallery is able to put on first class exhibitions which take on a wide range of themes. However, MIRRORCITY is a step too far; by trying to cover all the bases it stretches itself too thin, until you can see through the veneer of the majority of the works to find the unimaginative premise underneath. Like many visions of the future, it promises wealth and riches, but at best delivers malaise and ennui; in that respect, at least, Ballard would be proud.

14th Oct 2014 to 4th Jan 2015

Hayward Gallery

Student tickets from £8