Her Naked Skin & the Legacy of Women Writers

Fred Fyles asks the theatre industry where the women playwrights are

In 1613, Elizabeth Tanfield Cary published The Tragedy of Mariam, the Fair Queen of Jewry. Taking its cue from Roman drama, it is a classic example of a Jacobean revenge drama, a tale of love, betrayal and murder. The play centres around Mariam, second wife of Herod the Great; at the beginning of the piece, Mariam believes her husband is dead, killed at the hand of Octavian. However, Herod returns, and his sister, Salome, manages to convince him that Mariam has been unfaithful in his absence. As punishment, Mariam is executed. What makes The Tragedy of Mariam special, unique even, is that it was the first play written by a woman.

This week, more than 400 years after Mariam was published, sees the opening of a new production of Rebecca Lenkiewicz’s play Her Naked Skin at Guildhall School of Music & Drama. The play, which was written in 2008, is set in the years preceding WWI, and describes the campaign for equal voting rights by the WSPU – more commonly known as the Suffragettes. Both of the plays use the past as a way of questioning the societal values of today, particularly those relating to women: Cary uses the idea of the Greek chorus to represent the patriarchal values of the day, allowing her to question their value; Lenkiewicz presents the lessons learned from the Suffragettes in a dramatic manner, thereby highlighting how things have changed since then. But how have times changed? Surely today, more than four centuries after Cary first set out to defy convention, things have improved for women in the theatre?

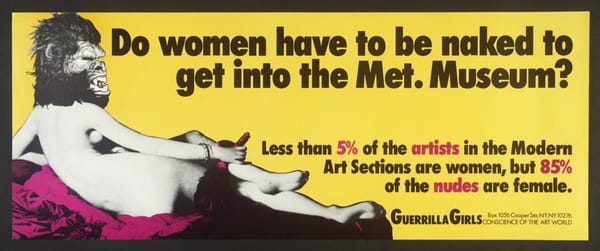

Sadly, they appear to have not. Lenkiewicz’ play, although very well received on its original run in 2008, it achieved more publicity for being the first original play written by a woman to be staged on the main stage at The National Theatre. That’s right. 2008. The National Theatre, held by many to be the finest tribute to theatre in Britain, if not the world, did not put on an original production written by a woman until a little over 5 years ago. This fact in itself is, for me, shocking, but if we expand our gaze, looking out further afield and back in time, the picture we paint for women in the theatre is grim indeed.

Let’s start with the National Theatre, which recently celebrated its 50th anniversary, and is perhaps the best-known theatre in the country. Surely, if British women playwrights are to have a place to call home, it would be here? Unfortunately not: in the first ten years of director Nicholas Hytner’s tenure - from April 2003 to April 2013 - the NT put on 206 full scale productions, of which a paltry 20 were written by women, less than 10%. Other theatres fare much better, with the Almeida, Hampstead, Soho, and Bush Theatres averaging 30% of their output being written by women, but this is far from ideal. In fact, the only theatre that comes close to reaching a balance is The Royal Court, whose output is 41% written by women, although perhaps this is to be expected, since the company champion new and eclectic writing. Recent estimates suggest that on the whole, only around 17% of produced plays have been written by women.

So why is there this disparity? Some blame the Western Canon, the collection of works regarded as ‘The Best’, from whose vaulted halls many women throughout history have been denied entry. While there is an argument – a strong one – to be made that the Canon marginalises any writers who aren’t white men, the world of theatre’s reliance on such work would almost certainly distort the types of plays being put on. With a rich history of Ibsen, Strindberg, and Chekhov to choose from, there is little incentive for theatres to attempt to take a chance on newer works. But recent productions have shown that introducing more women onto the boards can have wide reaching benefits for the whole cultural landscape: Phyllida Lloyd’s all-women production of Henry IV recently finished its run at the Donmar Warehouse to rave reviews, while the Royal Shakespeare Company – which would have perhaps the most legitimate excuse for ignoring women out of all theatre companies - is making active steps to bring a more balanced view to their output, adapting two of Booker Prize winner Hilary Mantel’s works for the stage. In this respect, the National Theatre in particular is dragging its feet: only 18% of their new plays were written by women.

But perhaps those plays written by women are just not as good as those by men? Such an argument, which seems to revel in the idea of the solitary male genius, simply does not hold water. One only has to look at the current state of theatreland to realise that a majority of the best plays in the last few years have been written by women: Lucy Prebble’s Enron, which fused music and high drama to tell the tale of the corrupt US energy giant, ran for nearly a year in the West End, picking up gushing critical reviews with ease; Laura Wade’s Posh, which premiered at The Royal Court, has recently been made into a film, The Riot Club, for which Wade wrote the screenplay; and Chimerica, written by Lucy Kirkwood, was perhaps judges as the play of 2013, garnering multiple award nominations during its West End run.

And it’s not just in the UK: Harvard economist Emily Glassberg Sands researched gender disparity on Broadway, and found that works written by women were on average 18% more profitable, and yet ran for the same amount of time as those written by men, adding weight to the idea that women simply have to be better in order to achieve the same as men. Sands also sent out identical scripts to multiple theatre companies, giving half a women author and half a male author; she found that the work written by ‘women’ was judged to be of lesser quality, and likely to make less money.

Times certainly may have changed since the days of Mariam, but the British world of theatre remains hostile to women: they can tread their boards, they can even direct their plays, but they cannot write their scripts. The UK in particular has a rich tradition of women writers, from Jane Lumley, who in the 16th Century became the first person to translate Euripides, to modern writers such as Abi Morgan and Caryl Churchill, and it therefore is so tragic for their work to remain unrecognised. History is, as they say, written by the victors, but for most of our history women have been banished from the paper, they have been robbed of the pen.

Her Naked Skin ran at Guildhall School of Music & Drama last week.