Crystallography turns 100

James Bezer on the triumphs of one of the most influential scientific techniques

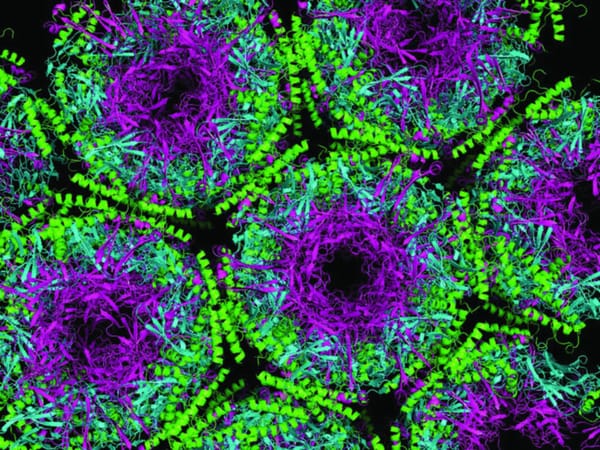

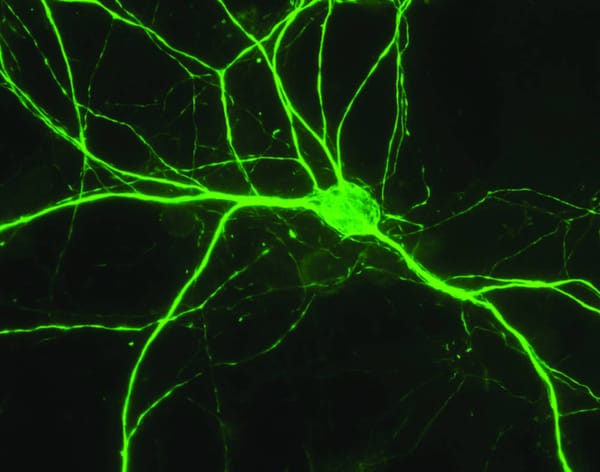

There are few scientific techniques that have had such an enormous influence across so many disciplines as crystallography. In the past 100 years, it has led to no fewer than 28 Nobel Prizes for discoveries from right across the natural sciences, and remains one the best ways we have of determining the nanoscale structure of everything from proteins to microprocessors. In an effort to raise awareness of the technique’s extraordinary achievements, the UN has named 2014 the International Year of Crystallography. The year was selected to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the award of the Nobel Prize in physics to Max von Laue, who first discovered that X-rays could be diffracted by crystals. Just a year later, the prize went to William Henry Bragg and his son William Lawrence for developing this technique to discover crystal structures. By firing X-rays directly at a crystal and observing the pattern they make as they pass through, they could determine the spacing between the layers of the crystal lattice, and its overall structure. The crystal acts a bit like a diffraction grating, with the waves being spread out by the spaces between atoms. For the waves to be diffracted, they need to have a wavelength as close as possible to the atomic spacing (a few hundred picometres), which is why X-rays are ideal. However, other particles, including neutrons and electrons, are also sometimes used. X-ray diffraction crystallography has given us a detailed understanding of much more complex molecules than the simple lattices the Braggs first looked at. Its most famous discovery came in 1953, at King’s College London, as a team led by Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins were trying to analyse DNA using X-rays. One of the biggest problems faced by Franklin and Wilkins was trying to create perfect crystals from DNA samples. Large molecules, like DNA or proteins, have to be extremely pure before they will crystallise, and it often takes weeks or months to get a good enough crystal to form. Eventually, they managed to produce an image of the molecule that allowed Francis Crick and James Watson, working under Lawrence Bragg in Cambridge, to establish the shape of the DNA double helix. Since then, crystallography has been widely used to determine the structures of a huge variety of biological molecules. In the 1950s and 60s, Dorothy Hodgkin became the first to determine the structure of vitamin B12 and penicillin, winning the 1963 Nobel Prize in chemistry for her discoveries. Even today, it’s still one of the best techniques we have of determining the structure of large molecules; one of the main uses of the £300 million Diamond Light Source in Oxfordshire, the UK’s national synchrotron facility, is to generate extremely intense X-rays for use in crystallography. In structural biology, major discoveries can be made about the behaviour of, say, a protein or virus, by getting a very detailed understanding of its shape. Just a few years ago, in 2009, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded for the discovery of the structure of the ribosome, the apparatus in cells that makes proteins, using the technique. But despite this list of achievements, crystallography remains relatively unknown outside scientific circles. Perhaps the International Year of Crystallography will help it be rightfully seen as one of the most important techniques in science.