Breakthrough in HIV gene therapy

Philippa Skett on the new gene-editing technique that gives HIV resistance

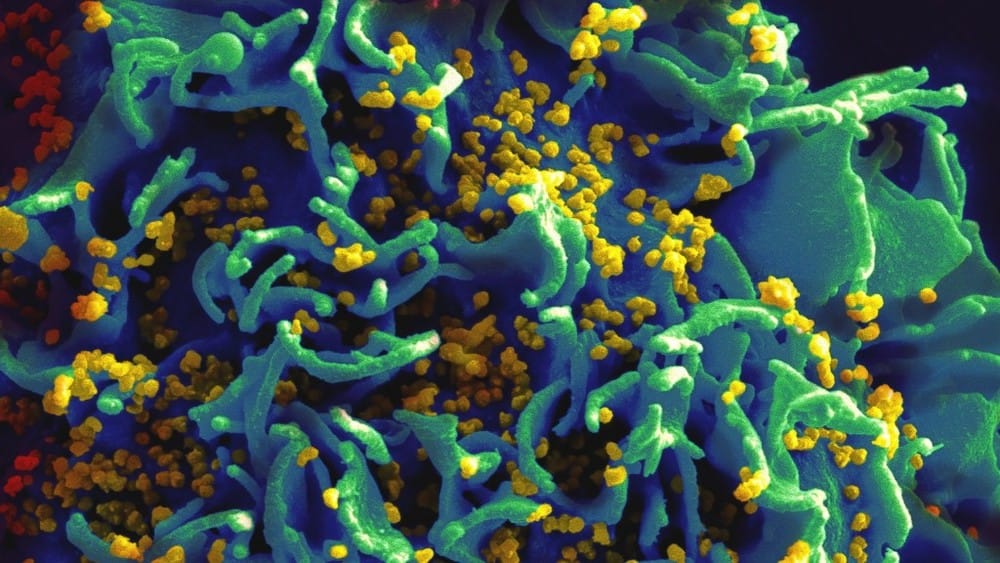

For the first time ever, researchers have succeeded in making enzymes target and alter the genes of immune cells that are susceptible to HIV infection. A clinical trial tested the enzymes, known as ‘zinc-finger nucleases’ and found that they were able to disrupt the gene CCR5, which codes a protein essential for HIV entry into T cells.

Although the clinical trial was only based on around 12 volunteers, it is a promising advancement in developing suitable HIV treatment. Results showed that disruptions in the CCR5 gene allowed for a significant elevation of T cells in the volunteers’ blood, indicating a decrease in the rate of successful HIV infection. Furthermore, upon half of the volunteers halting their antiretroviral drug therapy, their HIV levels increased more slowly than expected.

With the presence of HIV, the T cells containing the modified gene proliferated more rapidly – it seems HIV actually contributed to its own downfall. Those who carry a mutation in the gene naturally are already resistant to HIV infection; in 2008 it was reported that patient Timothy Ray Brown was free from HIV after receiving donor bone-marrow stem cells that already boasted the disrupted versions of the gene. Unfortunately the provision of donor bone-marrow stem cells is not an option for many people who are infected with HIV, as the body is very likely to attack the donor cells. Unfortunately the HIV soon reappeared in Brown, delivering a sobering blow to the research community at the time. However, with this “gene-editing” technique, it seems that things are looking up again.

One participant in the study was lucky enough not to have the virus return at all during the entirety of the 12-week period during which the anti-viral therapy was paused.

Upon genome analysis, it was revealed that this participant actually already had one of the CCR5 mutations. Once the genes were modified, over half of the T cells in his body were resistant to HIV. “Nature had done half of the job,” says Pablo Tebas, one of the immunologists leading the team at the University of Pennsylvania, where the study took place.

The next stage is to wean people off antiviral drugs altogether when undergoing the gene disruption treatment, and it seems that this could be a possibility. Other research groups are using the same group of enzymes to alter gene sequences in haematopoietic stem cells, which could potentially allow patients to make their own HIV resistant cells indefinitely.

Not only that, newer enzymes may actually be able to replace DNA as opposed to disrupting it, and these could be used to help treat a multiple of aliments from sickle cell anaemia through to cancer. Could enzymes truly be the ultimate editors? Only time – and a lot of research – will tell. DOI: 10.1038/nature.2014.14813