You can’t teach an old virus new tricks

James Bezer on the giant virus that is still infectious despite its age

After spending 30,000 years lurking deep within the Siberian permafrost, an enormous virus has escaped its icy lair. Even after all those years encased in ice, it’s still deadly. But this isn’t the plot of a low-budget horror film. This is real science.

If you’re feeling worried, don’t panic. Fortunately for most of our readers, this particular virus is only deadly if you happen to be an amoeba. But even so, the fact that a microbe could still be infectious after such a long time in ‘hibernation’ raises a worrying thought. Could human diseases like smallpox, that we have managed to subdue, be released into the environment by melting permafrost?

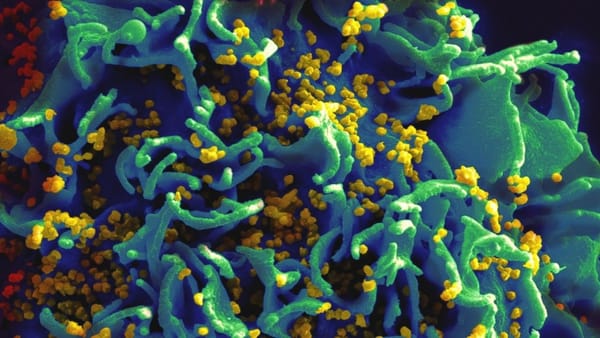

Researchers at Aix-Marseille University discovered the virus in an ice core taken 30m underground in the far northeast of Russia. Once they had defrosted it, they discovered that it could still invade an amoeba, hijacking the cell’s apparatus to make copies of itself. This is the first time that a virus this old has been shown to still be infectious. With rising global temperatures, this may suggest the possibility of more dangerous ancient viruses emerging from the ice.

The team’s investigations, published in the journal PNAS, show the virus in question is remarkable for more reasons than just longevity. At 1.5 micrometres in length, Pithovirussibericum is the largest virus ever discovered, and is similar in size to many bacteria. It’s more than ten times the size of an average flu virus (usually around 50-100 nanometres), and is so big that it can even be seen through a regular light microscope. It contains over 500 genes – 50 times the number found in a typical flu virus.

Pithovirus is one of a number of giant viruses to have been discovered in recent years. In 1992, scientists in Bradford identified what they thought was a new type of bacterium, but it was only in 2003 that it was shown to actually be a huge virus. Just last year, another, named Pandoravirus, was discovered in a sample from the coast of Chile. Under the microscope, they have a fairly broad range of sizes, although their shapes and structures appear alike.

But surprisingly, despite their external similarities, there are significant biological differences between them. Pandoravirus has about 5 times as many genes (about 2,500) as Pithovirus, and the two share only a handful of proteins. They also attack other cells in different ways: Pandoravirus uses the cell nucleus to replicate, whereas Pithovirus only requires structures in the cytoplasm.

Their evolutionary relationships, though, remain a mystery. The unique features of these viruses have led to speculation that they may constitute a fourth domain of life, alongside eukaryotes (such as plants and animals), bacteria and archaea. Whatever their true origin, the discovery of these giant viruses, and the huge variation between them, has been a vivid demonstration of the extreme diversity of microbial life.