The Great Cover Up

Rhian Jones discusses the depiction of the male nude in Western art

Back in February,Felix ran an article on the history of the female nude in art. But what of the male? The female nude is omnipresent and openly celebrated in Western art; she adorns the walls of today’s galleries, magisterially inviting our appreciation. By contrast, her male counterpart is overwhelmingly underrepresented. Pendulous phalluses are few and far between.

Historically, this was not always the case. Until the 19th century, nudes in Western art were predominantly male. Over the centuries our society has developed a double standard in our attitude towards nudity – whilst female nudity has become increasingly accepted, that of the male has become somewhat taboo. However, current censorship of men’s bodies is a sad reflection of the male nude’s illustrious history in art.

The male nude was central to early classical art; as a paragon of beauty and embodiment of philosophical ideals. Nudes such as Myron’s _Discobolus _450-460BC (a marble copy of which can be seen at the British Museum) represent a Greek aesthetic ideal. Poised mid-throw, the athlete has the kind of physique many gym-goers today dream of attaining, his muscular thighs and gleaming buttocks symbols of his masculinity. To some extent, such sculptures are imitations, a reflection of everyday life in Ancient Greece, where athletes traditionally competed naked. However, to depict a subject nude was also to venerate him - sculptures of mythological heroes and Gods stand naked alongside athletes. As a society open to male sexuality and homoeroticism, the Greeks saw no shame in male nudity. By contrast, until Praxiteles’ nude Aphrodite, female deities in art were typically robed.

The introduction of Christianity in Europe saw a decline in both male and female nudes in art of the Middle Ages, and perhaps set a precedent for censorship of the male body. Nude studies were only deemed acceptable where necessary in religious representations, marking an end to the Greek and Roman exaltation of the male form.

The Renaissance heralded his return, as an idealised form to study “mankind” in anatomical drawings, and with the resurgence of neoclassicism. However, with prevailing religious ideals, depiction of the classical nude had become problematic. Renaissance Europe’s reverence for Greek ideology and philosophy did not extend to acceptance of male nudity and homoeroticism. Nudes are not asexual – the art historian Kenneth Clark said “no nude…should fail to arouse in the spectator some vestige of erotic feeling… if it does not do so it is bad art”. But the majority of Renaissance artists were male, and homosexual acts were punishable by death.

Paradoxically, the threat of religious censorship appeared to liberate Renaissance artists in their representation of the male nude. Many religious paintings of the period are at once erotically charged and violent in their punishment of the male nude for the sinful feelings he evoked in the viewer; the rippling torso of Boticelli and Mantenega’s St. Sebastian is studded with arrows. Such works associated the male nude with a new vulnerability absent from the heroic nudes of classical art.

Elsewhere, sensuality began to creep into male nude artworks, providing an outlet for homoerotic feelings prohibited by society. Donatello’s _David _sculpture, one of the first examples of a classical male subject studied from life, is overtly seductive. Hand on hips, his come-hither stance and curvaceous contours also break from traditional depictions of the male nude. Threatened by the emerging eroticism in male nude artworks, the church continued to censor them. Fra Bartolomeo’s painting of St.Sebastian was removed from a Florentine church after female parishioners confessed to lusting after him, and the Vatican famously painted drapery over any offending male genitalia in Michaelangelo’s Last Judgement in the Sistene chapel following the artist’s death.

Although Renaissance art saw a rise in popularity of the female nude, it was not until the 19th century that she really began to eclipse the male. Mastering the male form remained a key part of an artist’s formal training, and prestigious art prizes continued to honour male nudes. However, the salons became inundated with female nudes, reflecting an emerging preference for the “softer” feminine aesthetic ideal. Male nudes came to be associated with obsolete and stuffy academic teaching. The art historian Solomon-Godeau suggests that post-Renaissance, masculine identity was in crisis, with artists torn between virility and vulnerability. Through transferring the latter characteristic to female nudes, the issue could be avoided.

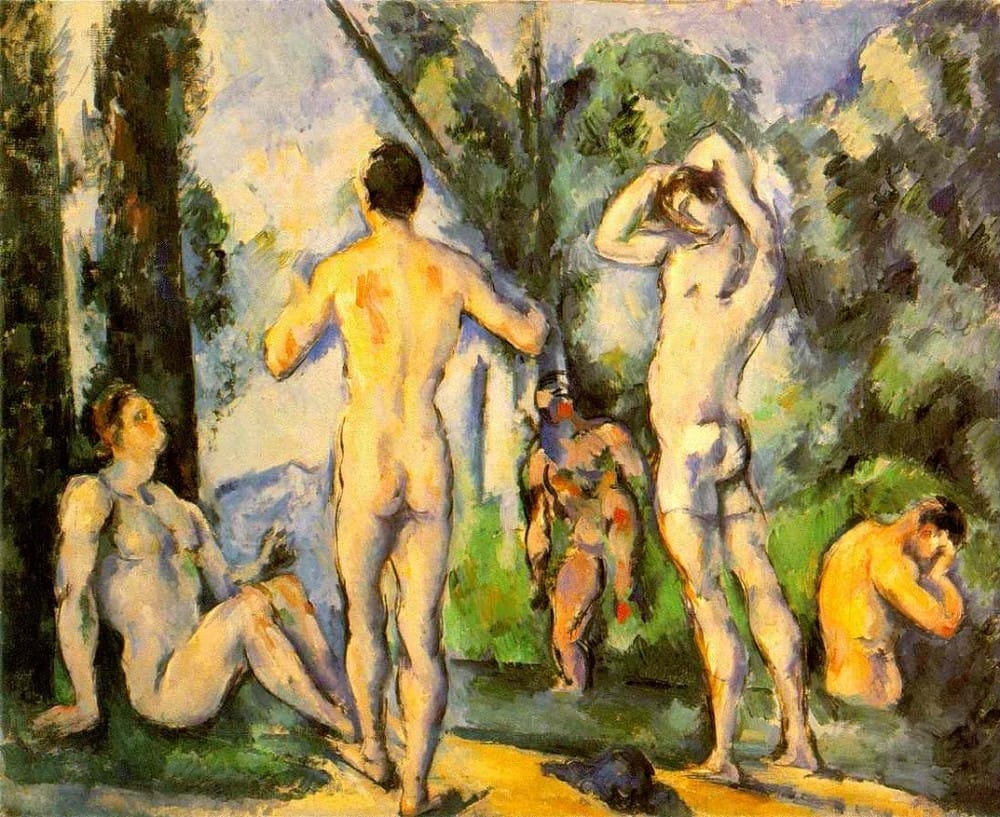

Despite its decline in popularity, the 19th and 20th century saw greater freedom in our attitude towards the male nude. Whilst the Impressionists’ female nudes are well known today, artists such as Cezanne painted men frolicking nude (Baigneurs, 1890) and Caillebotte’s paintings of men undressing have the same voyeuristic qualities as Degas’ female nudes. The arrival of the realist aesthetic also led to the representation of different body types in art, further challenging traditional concepts of masculinity. Egon Schiele’s gaunt self-portraits are a far cry from the classical nudes of old. Meanwhile, female and homosexual artists have provided important perspectives that deviate from the typical “male gaze”- artists such as Alice Neel paint men in reclining poses typically associated with female nudes, focussing on her subjects’ vulnerability. Andy Warhol’s and Jean Cocteau’s sketches of male lovers are both unashamedly erotic and lovingly tender.

So with today’s freedom of expression in art, why are we still so uncomfortable with the male nude? An obvious answer is that the art industry is still predominantly controlled by heterosexual men, who may prefer to ogle females than self-scrutinize. It has also been argued that viewing a male nude places us in the uncomfortable role of the “male gazer”. In a study where psychologist Beth A. Eck’s assessed people’s responses to male and female nudity, male nudes sparked feelings of “lust mixed with guilt or shame” in women, whilst many men admitted to feeling uncomfortable. Why does the female nude not incite similar feelings? Many have suggested that as the male sexual organs are external, they are more of an affront to the senses; symbols of sexual aggression. By contrast the female nude is “neater”. Yet art demonstrates that this is not so - the male nude can be beautifully tender.

The art world is at last beginning to re-acknowledge the beauty of the male nude- recently the Leopold museum in Germany and the Musee d’Orsay in France held exhibitions dedicated to artistic portrayals of the male form (Naked Man and Masculin/Masculin). However, somewhat ironically for a museum seeking to open our minds to male nudity, the Leopold museum was asked to censor many of its’ advertisement posters. In a society obsessed with female nudity, it is high time that the male reclaimed equal status in art.