What A Testament

Fred Fyles is blown away at the Barbican

Who was Mary? From biblical sources we know that she was the mother of Jesus; from them on it gets a little fuzzy, depending on which line of Christianity you’re following.

But who was Mary really? Was she a saint, who ascended to heaven during the Assumption? Or was she just an ordinary woman, who happened to raise one of the most influential men in history? It is this question that Irish writer Colm Toibin is attempting to answer with The Testament of Mary, a radical reinterpretation of Mary’s life that veers away from the accepted dogma. Nominated for the Booker Prize in 2013, _Testament _has since been adapted for the stage by Toibin himself, who cuts down his slim novella, which comes in at under 100 pages, to an even more slimline monologue, delivered over the course of 80 minutes by fellow countrywoman Fiona Shaw.

Shaw’s Mary rejects the accepted view of Christ as saviour; holed up in a small house in Ephesus, she is regularly visited by followers of her son, who want to write up her story, but she isn’t telling them what they want to hear. In a voice laced with cynicism, she decries her son and his apostles as “a bunch of misfits”. Picking up his story from childhood, through to his crucifixion, Mary makes it clear that she has no time for her son’s so-called ‘miracles’. Preferring to live in ‘the cold light of day’, she explains how stories of his healings were passed along like Chinese whispers, how Lazarus’ miraculous resurrection was anything but, and how even his turning water into wine – an event she was there to witness – was unconvincing. Overall, this is a stark rejection of the accepted Christian dogma, and it is perhaps no surprise that the play met with protests when it opening in America last year.

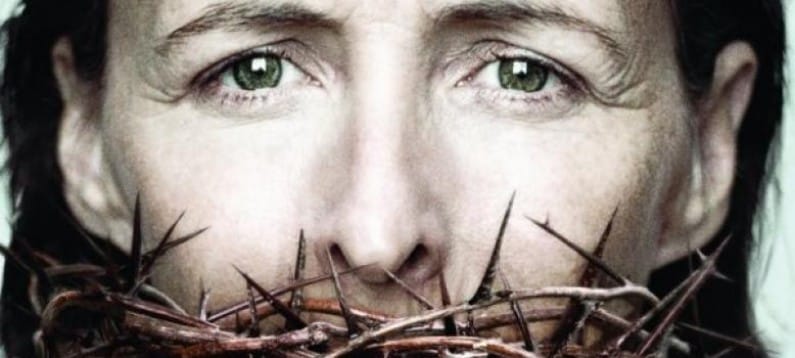

Shaw pulls no punches in her portrayal of Mary, and brings an intense physicality to the stage, which she stalks like a caged animal, pacing up and down. In a clear, strong voice, which has at its core a sense of anguish, she recounts how her only son grew away from her, and was eventually murdered in front of her eyes. This Mary is not heroic. She is a deeply scarred woman, who fled the crucifixion for fear of her life, and now harbours an anger at the outside world, and an even deeper anger at herself. “Nothing escapes me” Shaw intones, her voice heavy with world-weariness, “except sleep”.

While Shaw’s performance is electrifying, and captures our attention to such an extent that the minutes slip by like seconds, the emotional core of the piece seems somewhat lacking. While the script progresses through the life of her son, there never seems to be an emotional climax, and the peak that is reached as Shaw describes the crucifixion is somewhat tempered by the intrusive sound design. At the end of the play there is no catharsis for Mary, and none for the audience either; all we have is a tired old woman, exhausted, and at the end of her rope. However, while keeping in mind that this lack of release may be intentional, it is nigh-on impossible to criticise Shaw’s performance, which I am sure will be remembered for years to come as one of her best.

When exploring the question of Mary’s identity, it is necessary to look at how she has been portrayed in the visual arts. A recurring motif throughout Western art, depictions of Mary can be found in nearly every European culture over the last millennium; but director Deborah Warner gives little concession to these images, donning her Mary in stark black peasant garbs, emphasising her normality. However, Warner does bookend the production with two classic depictions of Mary: for twenty or so minutes before the play begins, the audience is invited to come up onto a stage littered with props, the most popular of which is an enormous live vulture, which is instagrammed passionately by the crowd. But the most striking feature is a glass tank, in which Shaw sits, surrounded by candles. Dressed in sumptuous robes of red and blue, she bears an uncanny resemblance to a Renaissance _Madonna of Humility. _Similarly, towards the end of the play, she picks up a bundle of robes, and assumes the classic image of the _Pieta, _in which Mary is shown cradling the body of her dead son.

While both of these images are striking, what gives them more impact is the fact that neither pose includes the figure of Jesus, making us acutely more aware of what Mary is missing. There is a gaping hole at the centre of her life, a child who died before his mother, which no amount of time can fix.

Aside from these two moments, the play seems to take its cues much more from 20th century art; Tom Pye’s stage design includes a massive, Richard-Serra-esque sheet of metal at one end, and the shifting light that forms the horizon is reminiscent of a desert dreamscape by Dali. In fact, the entire production has the air of a dream about it, with Pye’s Ephesus seeming to be removed from both time and space. This raises issues about the veracity of the literature we are presented; how accurate is the Biblical story? And for that matter, how accurate is Mary’s telling?

The answer to both questions in unknowable, and Warner makes these points with a lightness of touch. In our modern, image-obsessed world, the only testament that matters is what people can capture with their iPhones and place a retro filter over (#testamentofmary).

Once the production finishes, and the house lights go up however, one thing is certain: Shaw has given a performance of a lifetime, and this groundbreaking production, which owes innumerable amounts to Warner and Pye, deserves to go down in the artistic canon, as one of the most brilliant portrayals of the Virgin Mary ever told.