Freedom of speech in a civilised society

Should freedom of speech be given when it threatens social peace?

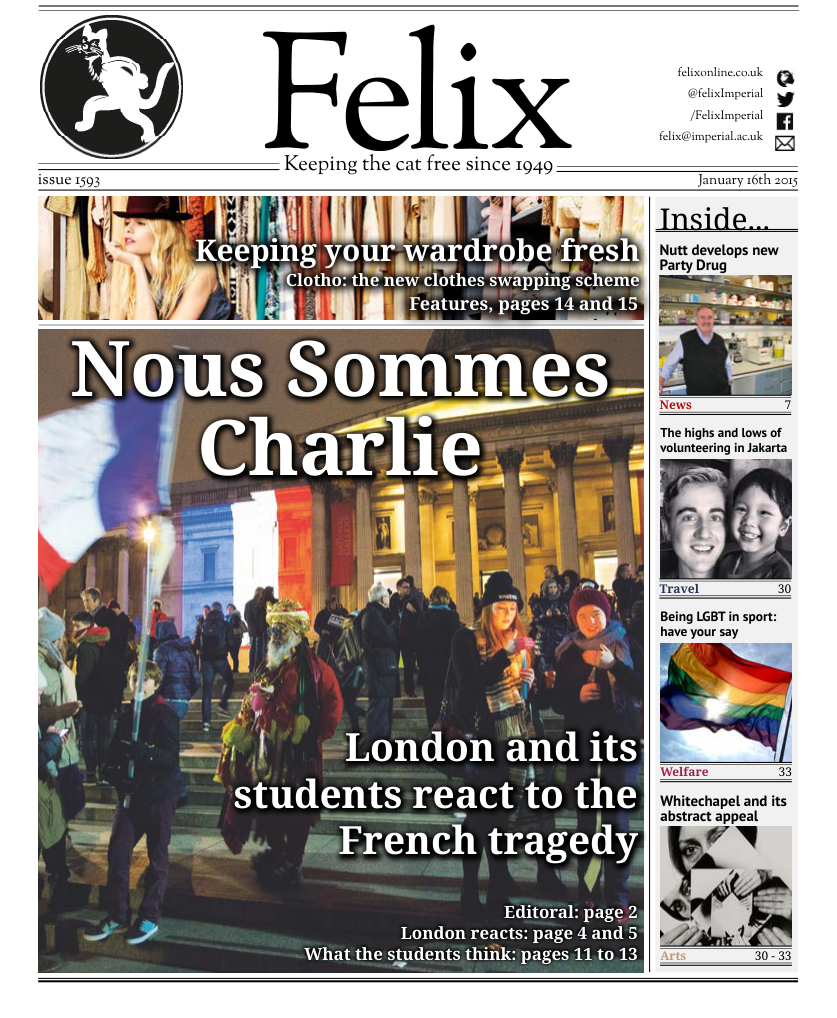

Last week’s heinous attacks on Charlie Hebdo caused an outpouring of grief and support from around the world for the innocents who lost their lives that day, and in the days that followed. The brazen assault was led by two masked gunmen claiming that they were avenging the name of the Prophet Muhammad, whose gross caricatures Charlie Hebdo had published in years gone by. And yet, 2 of the 12 murder victims that day were Muslim – one named Ahmed, the other Mustapha – both names of the Prophet Muhammad, a telling symbol of the character assassination that took place that day. In the coverage that followed, it became clear that the terrorists did more to defame the name of Islam than any cartoon ever could.

It should be absolutely clear that these attacks were the antithesis of Islam’s peaceful teachings. The Qur’an does not allow any act of terrorism, likening the murder of a single innocent to the murder of the whole of mankind (5:32). One wonders then, how many Earths these terrorists would fill with blood. At this point, critics often join hands with extremists in misquoting verses regulating rules of warfare, whilst hiding the proviso that such warfare is explicitly only permitted in defence of innocents who have been attacked first (22:39), who have undergone severe persecution and whose legitimate rights have been ransacked (2:191-193). Freedom of conscience too is enshrined as a fundamental human right in Islam: “There is no compulsion in matters of religion,” it says, effectively rebutting the totality of extremist ideology in just a few words (2:256).

With this said, the attacks have reignited the debate over how civilised society should practice freedom of speech. From the vile film released a few years ago, to the cartoons published by several European outlets, caricatures made of the Prophet Muhammad have repeatedly hurt the sentiments of 1.6 billion Muslims the world over. In the wake of last week’s attacks, western media has wisely refrained from re-publishing any of the concerned cartoons, but there is a strong sense that this was more out of self-protection than responsible editing. “Publish and be damned” was the Independent editor’s initial reaction, only tempered, he said, by a duty towards his staff. Worryingly for Muslims, two thirds of the British public would also support their publication, as a YouGov poll revealed last weekend.

This kind of reactionary abandon is understandable, but misplaced. Free speech itself is a means by which society can exchange productive ideas and become better informed as a whole. However, when such an exchange threatens social peace and unnecessarily vilifies parts of the population, it is always curtailed. For instance, the French Catholic Church successfully blocked an ‘offensive’ advert depicting the Last Supper in 2005. Charlie Hebdo themselves fired one of their cartoonists in 2008 for an anti-Semitic article and cartoon. In general, western society acknowledges that gratuitous insulting, which serves no other purpose but to incite hatred and divide society, should be censored. The art of satire lies in the weak highlighting the inconsistencies of the powerful. Caricaturing the beloved hero of the already beleaguered French Muslim population, whose women cannot even wear headscarves whilst employed in public service, is a gross caricature of satire itself.

This does not mean to say that Muslims hold Islam to be somehow above criticism and debate. Muslims do not seek preferential treatment, but equal treatment to other populations whose sentiments are routinely safeguarded. Horrendous though the attacks were, the British public mustn’t let them knock askew their usual poise on issues like these.

For the time being, as a Muslim, I take the Prophet Muhammad as my role model in dealing with attacks on his character. Not only was he slandered repeatedly in his own lifetime, but several attacks were made on his life. Through it all, he stuck to the teachings of the Qur’an, to ‘bear patiently with what they say’ and turn to prayer for success (20:130); to ‘turn away’ from the slanderers, and ‘keep on preaching’ to those who would listen (51:54-55). Not only this, but he was deeply sensitive to the sentiments of others. On one instance, he rebuked a Muslim for having said to a Jew that the Prophet Muhammad held a station higher than the Prophet Moses. Though this was consistent with Islam’s teachings, he disliked the idea that religious beliefs were being expressed in a way that would unnecessarily hurt the sentiments of others. With rights come responsibilities, he taught, and the commitment to social peace is one we must all fulfil.

This teaching is not just a thing of the past. A contemporary Muslim spiritual leader whom I follow exhorts the very same in this day and age. After the infamous 2012 film caricature of the Prophet Muhammad, Mirza Masroor Ahmad, Caliph of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, counselled all Muslims to respond productively. He said they should defend Islam not with violent demonstrations, but through reforming their characters and by educating people about the true character of the Prophet Muhammad. But he also advised the public at large to use their freedoms responsibly, saying, “Let it not be in the name of freedom of speech that the peace of the entire world is destroyed.”

The tragic attacks last week have given all sections of society much to think about. Condemnation has resounded from all quarters, but we cannot follow up injury with insult. We must defeat the terrorists by showing them that we will not let extremist thinking of any kind dominate our mindset, and that we will continue to safeguard the rights and sentiments of all sections of our society – an idea that is anathema to their twisted ideals. In defiance of them, we would all do well to take the following as a motto in these trying times: “Let not a people’s enmity incite you to act otherwise than with justice. Be always just – that is nearer to righteousness.” (Qur’an: 5:8).