Artificial Intelligence with a Consciousness

Lauren Ratcliffe on an Imperial professor’s involvement in the film Ex-Machina

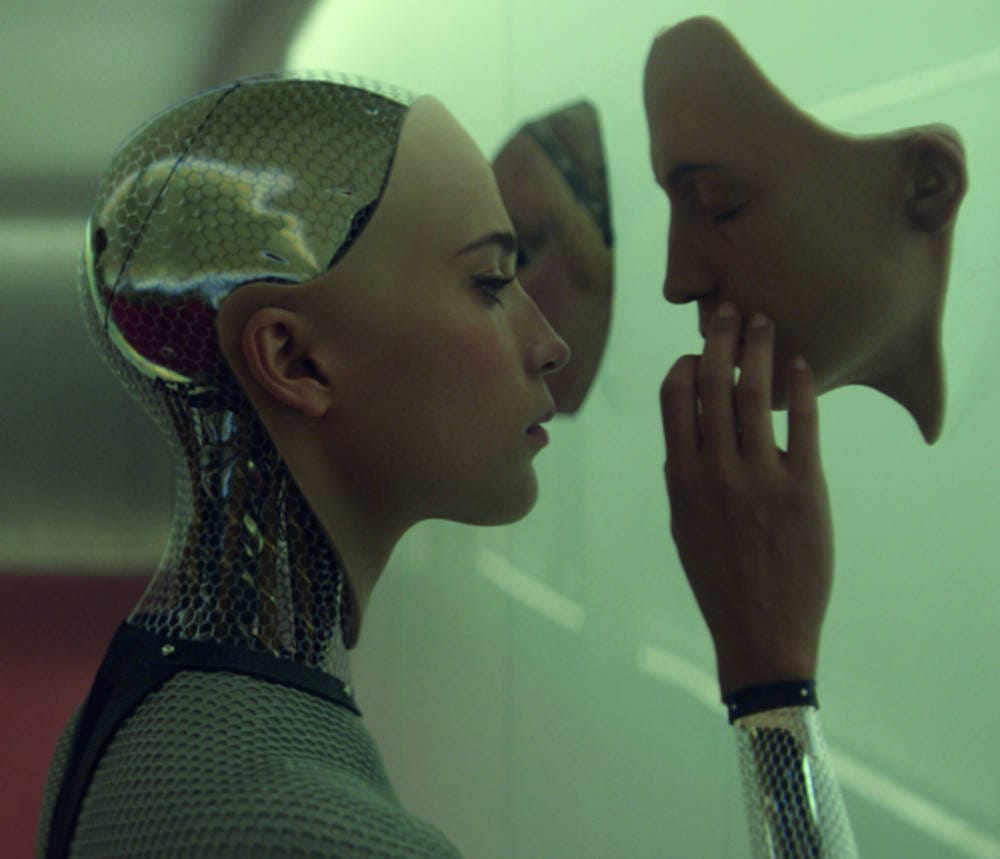

Science fiction film Ex-Machina has recently hit cinemas worldwide, a psychological thriller to tantalise our over-active imaginations of a future where artificial intelligence has a consciousness. But how far are we from any of these ideas becoming reality? In Ex Machina audiences are supposed to believe that the artificially intelligent character, Ava, has a sense of self. Young programmer Caleb is asked to test Ava’s consciousness and reveals that Ava is a bonafide intelligent huminoid capable of feeling emotions. The suffering she later experiences in the film evokes within us a sense of injustice; if she has a consciousness surely she should be entitled to freedom?

Alex Garland, the director of Ex-Machina, was inspired by Imperial Professor Murray Shanahan’s book: “Embodiment and the Inner Life: Cognition and Consciousness in the Space of Plausible Minds”. Shanahan’s research at Imperial looks into how the human brain function could be used in the field of artificial intelligence (AI). “I am interested in trying to understand how cognition is realised in the brain. To do this I build computer models, which are typically simulations of large numbers of neurones organised in a complex network,” he says in an interview at Imperial. After reading the progress in theory of consciousness detailed in Shanahan’s book, Garland contacted the professor for advice on the technical aspects of his film.

Origins of Artificial Intelligence

AI and machine learning algorithms are surprisingly ubiquitous in our everyday lives: Google’s search predictions, mobile phone voice recognition systems such as Apple’s Siri, driverless cars like Tesla Motors’ latest dual-motor Model S and even closer to home – number plate recognition technology used for the London congestion charge. However, we are still a long way off being able to use robots instead of all-nighters to desperately complete our university coursework.

The progression of AI from the pages of Isaac Asimov’s science fiction stories to driverless cars all started in the 1950s with Alan Turing, a British mathematician and infamous WWII codebreaker. It was Turing who first posed the question of whether machines could think, developing the Turing test, which determines how close a machine’s behaviour is to that of a human. It is this that forms the basis for the plot of the film Ex-Machina.

Through the 1960s and 1970s Marvin Minsky, an American cognitive scientist, became a leading thinker in the field and co-founded the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) shortly after Turing died in 1954. Similar to Professor Shanahan, Minsky was scientific advisor to director Stanley Kubrick on the 1968 science fiction film “2001: A Space Odyssey” which brought audiences the AI called HAL9000 aboard spacecraft Discovery One.

After what was termed an “AI winter” between the 1970s and 1990s, when funding was cut short as governments favoured more productive industries, the 21st century saw the advancement of AI technology, albeit in less obvious ways than human lookalike robots. Nowadays, AI research is focused more on behind the scene uses such as logistics, data mining and medical diagnosis. One crazy example is in Japan where an AI has been nominated as a board member in a venture capital firm as it can predict market trends faster than its human associates. AI is also being used in the defence industry, with South Korean forces now using Samsung SGR-1 armed sentry robots to patrol the boarder with North Korea, and in Iraq and Afghanistan.

There have also been advances in robots that can develop and show emotions. Nao, a robot developed by the French robotics company Aldebaran, is being used as a robotic teacher in universities and schools across the UK. The uncannily human-looking robot stands two feet tall and can be programmed to listen, see, speak, touch and react. If you search ‘Nao robot’ on YouTube you can even see troops of them programmed to dance in sync with the pop-hit Gangnam Style. Their abilities extend far beyond the dancefloor however, and they can even form bonds with the people they meet – depending on how they are treated. The longer they interact with someone, the more Nao learns the person’s moods and the stronger the bond becomes.

Growing concerns

The usefulness of these technologies, with their capacity to continually learn from the data they collect, is making it ever harder to imagine a future without AI. Increasing dependence on these machines has sparked some concerns, with even Stephen Hawking warning of the perils of AI, saying in an interview with the Independent: “The development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race ... humans, who are limited by slow biological evolution, couldn’t compete, and would be superseded.” The technological singularity hypothesis represents this view that continued progress in the development of AI will ultimately cause the end of humanity as its power exceeds mankind’s intellectual capacity to control.

If you follow popular culture ss a guide to AI, then we really should be terrified. Most fictitious depictions of a future where humans and robots co-exist picture bleak apocalyptic scenarios, ranging from robotic conspiracies to take over the world in _I-Robot t_o the dystopian Earth depicted in the film _Blade Runner _where robotic ‘replicants’ have spiralled out of human control.

Whatever your stance on the future of AI, its progress since the 1950s has showcased the incredible capacity of humanity’s own intelligence. It has certainly helped advance sectors such as medicine, defence and business. But how long it will take to create robots that have consciousness is still debated. Shanahan comments on the topic saying “the Robotics side of things – Ava’s body – we can get to in 10 or 15 years I think ... but Ava’s consciousness requires a couple of conceptual breakthroughs before we get there”. Therefore despite substantial progress we are still far from making the ideas portrayed in Garland’s film a reality, though it’s certainly not impossible.