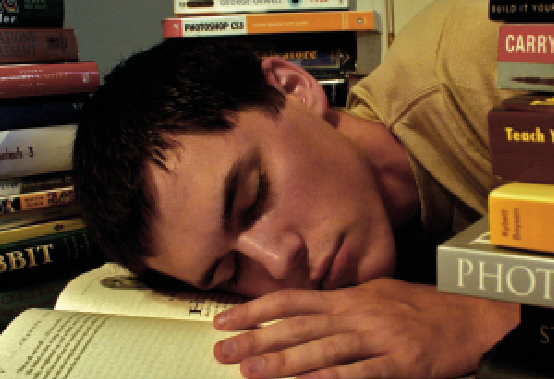

All-nighters might not be such a good idea

Another good reason not to sleep in the library

It’s coming up to that time of year again where a lot of us start to panic and furiously try to catch up with all the lectures we’ve been procrastinating in since last October. However, is pulling all-nighters for the last few weeks leading up to exams really worth our while?

Researchers from Brandeis University in the United States have recently illustrated a new perspective on our understanding of the relationship between sleep and memory consolidation, arguing for a significant role of inhibitory neurotransmission in regulating these processes.

Sleep, which is defined behaviourally by the normal suspension of consciousness and electrophysiologically by specific brain wave criteria, consumes a whopping third of our lives! So is it any wonder that we’ve known for a long time now that sleep, memory and learning are deeply connected?

Previous studies have shown that when animals such as mice – and even humans! – are sleep deprived, they tend to experience a lapse in their memory.

More recent research has shed light on the fact that sleep is critical in converting short-term memories to long-term memories, a process known as memory consolidation. However, we are as yet unsure of the details of how this works.

Are memories reinforced because during sleep, our brain has more time to ‘replay’ all the events of the day and filter out the unwanted memories from the wanted ones, or are ‘memory neurons’ in the brain the reason why we feel sleepy in the first place?

Paula Haynes and Bethany Christmann, of Brandeis University, led a project that studied well-known memory consolidator neurones in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, called dorsal paired medial (DPM) neurons and examined how these interacted with wakefulness-promoting neurones, called mushroom body (MB) neurons. The mushroom body is a section in the Drosophila brain where memories are stored.

Interestingly, they found that when the DPM neurons were activated, they released an inhibitory neurotransmitter called GABA which decreased the activity of the MB neurons, making the flies sleep more. When this system was deactivated by downregulating two of the MB neurons’ receptor subtypes (the GABAA and GABAB R3), there was increased loss of sleep in the flies.

This intimate regulation of sleep by neurons necessary for memory consolidation suggests that these brain processes may be functionally interrelated through their shared anatomy. These memory consolidation neurons inhibited the drive for wakefulness as the conversion of short-term to long-term memory commenced.

Bethany Christmann, co-author of the study which was published in the journal eLife, explained that “It’s almost as if that section of the mushroom body were [initially] saying ‘hey, stay awake and learn this’ ... then, after a while, the DPM neurons start signalling to suppress that section, as if to say ‘you’re going to need sleep if you want to remember this later’”.

These findings have important implications for understanding the relationship between sleep and memory consolidation, by supporting the role played by inhibitory neurotransmission in the regulation of these processes. Further development of our understanding of the relationship between sleep and memory in a simple system such as the fruit fly may hopefully take us a step closer to unravelling the complex mechanisms behind sleep and memory in the human brain. Christmann also mentioned how this research could “help us figure out how sleep or memory is affected when things go wrong, as in the case of insomnia or memory disorders”.

In the meantime, if you want to ace that paper tomorrow, put down that can of Red Bull and hit the sack!

DOI: 10.7554/eLife.03868.001