House: A Post-Mortem

Joshua Renken offers a final retrospective on this long-running medical drama

If you have never watched House, I envy you. It is one of the most nuanced and intelligent shows ever created, and there are 177 episodes for you to enjoy for the first time. In the eight years that House ran (2004-2012) it was distributed to over 60 countries and at one point had the highest worldwide viewing figures of any television series. While the idea of a new medical show for Fox network originated with Paul Attanasio, it was David Shore, credited as creator, who conceived the titular character that made the series so captivating.

The series centres on the life of Dr. Gregory House: a misanthrope if ever there were one. House is a drug addict who depends on Vicodin pills to manage the pain caused by an infarction in his quadriceps muscle five years prior. His reputation as something of a medical genius carries weight at Princeton Plainsboro Teaching Hospital, an institution headed by Dr. Lisa Cuddy (Lisa Edelstein). Leading a team of elite diagnosticians at PPTH, House takes on the cases that other doctors have not been able to solve, in an attempt to “diagnose the undiagnosable.”

At the beginning of the show his team consists of Dr. Chase (Jesse Spencer), Dr. Foreman (Omar Epps) and Dr. Cameron (Jennifer Morrison), but the composition of his diagnostic team undergoes several changes. This chopping and changing of characters kept the series fresh in the fifth and sixth series, a point at which many shows begin to think about finales.

House was one of the first series to put an anti-hero as the main protagonist

But really this show is all about House. The team primarily serve to create talking points for our troubled protagonist, who regularly probes into their personal lives in an attempt to understand his employees better; very attentive when it comes to the behaviour of his team, there is rarely something he misses. House expends a huge amount of energy avoiding his responsibilities as a doctor, so he has time spare to mull over the patient’s condition (they work case-by-case), gossip with Wilson about Cuddy and investigate into the private lives of his team. A stubborn and principled man who thrives on conflict, he believes that his employees will work best in a chaotic environment where they are constantly trying to outdo one another. With each batch of employees he quickly creates a competitive environment and under House’s tutelage his fellow physicians learn to distrust what their patients say. He encourages them to stand up for what they believe and fight for their ideas. The team bend the rules if they feel that it is not in the best interests of the patient and often break into the patient’s home without permission. Perhaps unsurprisingly, House’s favourite mantra is “everybody lies”.

Each week there is a new case, which House typically solves after a few erroneous diagnoses, but the team screw up regularly enough to keep you guessing. It is explained in the pilot episode that House is one of the best in the country at finding medical ‘zebras’ when other doctors are looking for ‘horses’. He has a knack for solving obscure medical puzzles that most other doctors could not.

House is a series that regularly deals with contentious issues including rape, abortion, religion, faith, and adultery. The momentum of the show stems from the intriguing cases which provide a bottomless source of ethical dilemmas and thought provoking topics for the characters to debate.

Dr. House frequently reaches an epiphany when in entertaining conversation with his confidant and only friend Dr. James Wilson (Robert Sean Leonard). Wilson is the Head of Oncology at the hospital, and acts as a sounding board for House to bounce ideas off; in many ways he is House’s conscience. House relentlessly mocks Wilson for caring so much about the people he treats, in one episode knocking on Wilson’s door and declaring, “I know you’re in there. I can hear you caring.” It is mentioned that Wilson has a Messiah complex; if true, then in contrast House has the Rubik’s complex. He just wants to solve the puzzle. Highly manipulative in his relationships, House often tests those around him to find their breaking points. He loves to play mind games with Wilson, and the duo often prank one another, often escalating until Cuddy has to intervene.

House is a deeply depressed character with a very cynical outlook on life; for all his existence he has been an antisocial maverick genius who struggles to connect with people. With a penchant for medical puzzles, playing the piano, Vicodin, alcohol, and hookers, House is simultaneously immature yet perceptive in his conclusions about life. He reacts on impulses and is only selectively rational. He strongly believes that people are purely self-interested, that everybody lies, that religion is a joke and that thoughts don’t matter. Only actions. He thinks there is no objective purpose to life and dismisses the lives he saves. It is through his solving of medical puzzles that he attempts to find deeper meaning, but he describes the lives he saves as “just collateral damage.”

This series gets darker as House’s behaviour becomes more extreme. He is always unstable and the people closest to him, Wilson and Cuddy, are in constant fear that he will go off the rails. They try to provide an atmosphere where House is given enough freedom to do his best work as a doctor, but not so much that he kills himself. Forever popping Vicodin pills in his mouth as though they were tic-tacs, in later series House begins to blur the boundary between physical and emotional pain, at one point justifying his substance abuse to Wilson by saying, “the pain doesn’t discriminate and neither do the pills.” His actions become more radical and lead to stints in both a psychiatric hospital and a prison. It would be fair to say that House is more of a meditation on misery or a deep character study of a compromised genius than it is a medical procedural drama.

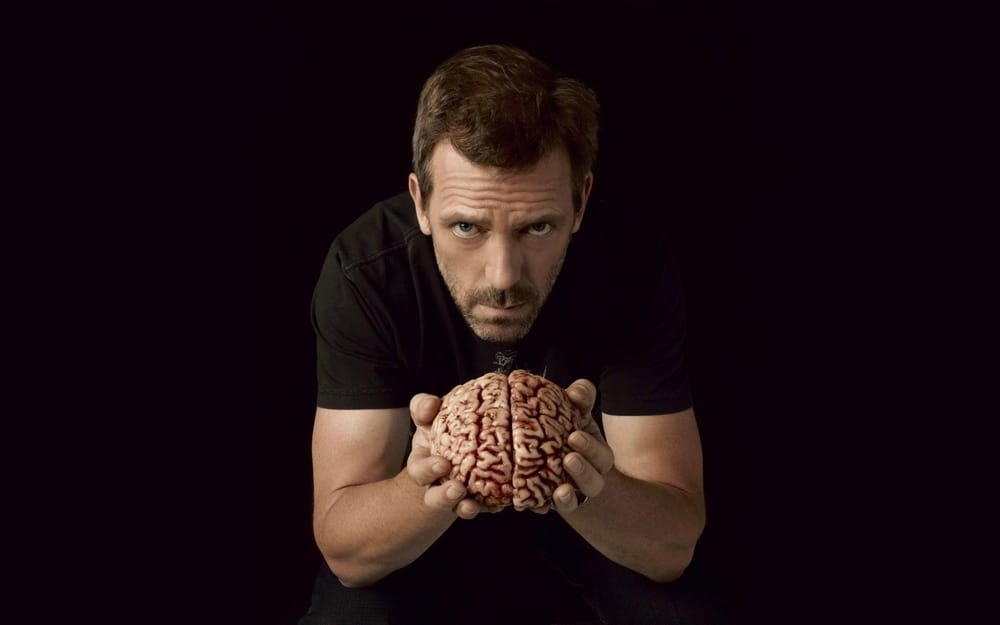

House himself is an enigma. His brain means everything to him and he has recognised that solving obscure medical cases somehow lessens the chronic pain in his leg – as though he were too busy with the puzzle to think about his physical vulnerabilities. While House portrays himself as very lazy, he often goes out of his way to prove a point or be in control; he rarely takes the path of least resistance and is always his own worst enemy. House is reluctant to form relationships because it makes him vulnerable and is constantly evading and deflecting in conversations. He tends to make light of morbid situations and never fully opens up to communicate honestly with those around him. This means that despite his inner demons, House is often very funny.

House is one of the shows that forged the path towards this new era of TV

Forever trying to escape his clinic hours – where he actually has to meet patients face to face – House also generally avoids visiting his non-clinic patients, since he believes that removing emotional biases and keeping objectivity makes him a better doctor, an opinion not disproved on the show. The short clinic scenes, however, provide light relief and make great use of Hugh Laurie’s comedic sensibilities – the series will make you laugh more thank you might think, largely due to the hugely satisfying ‘Houseisms’ that grace the series. In one episode an inspector remarks, “Dr. House, I’ve heard your name.” to which he replies “Most people have, it’s also a noun.” In one confrontation over a colleague, House tells Cuddy “I don’t want to say anything bad about another doctor... especially a useless drunk.”

House has an uncanny ability to ‘read’ people and diagnose their ailments simply by looking at them; this talent is just one of the many similarities between House and the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes. House’s intelligence, deductive reasoning skills, social awkwardness and powers of observation are near identical to Sherlock’s. Furthermore, both House and Sherlock play instruments, take drugs and have one true friend (Wilson/Watson). House even lives in flat 221B, essentially making the series a modern day Sherlock, albeit with a medical degree.

It is often the case that actors do a great job in their roles, and it is easy for the compliments made about their achievements to lose their punch, but it has to be noted that Hugh Laurie puts in a truly mesmerising performance as House. As discussed above, the titular character is one of the most nuanced and demanding parts that has ever been played on the small screen, and Laurie delivers in full.

Hugh Laurie has said that when he first read an early sample of the script he instantly felt that he understood this cranky doctor. Assuming that, due to House’s personality and conversational style that, he was planned to be a “quirky” side member of the cast, it came as a surprise to Laurie that House’s life, work, and opinions were in fact the whole foundation of the show.

David Shore explained that when he and others got hold of Laurie’s five minute audition tape, one of the executive producers said, “See, this is what I want; an American guy.” This is impressive in itself, but even more so when you consider that Hugh is in fact about as quintessentially British as it is possible to be.

The rest of the cast put in a universally top rate performance and the quality of the writing never dropped. The scripts remained as witty and thought provoking as they were at the beginning, an incredible achievement when you consider the sheer number of episodes.

This series was nothing if not bold, being one of the first television series to put an anti-hero as the main protagonist. Before the turn of the century the vast majority of leading men and women were depicted as moral supermen. House wasn’t the first, but it was certainly one of the very best shows to embrace the idea of having a leading role that on paper the audience should dislike, if not actively hate. House’s character was a controversial figure, steadfastly holding views that were not all that popular and often taboo. But the show’s success has led to the mainstream adoption of this new direction for television; we have seen a huge influx of more conflicted, damaged and all round realistic central performances ever since House’s premiere way back in 2004. The quality of television has never been higher than it is now and House is one of the shows that forged the path towards this exciting new era.

When the producers announced that the eighth series was going to be the last, fans were not demanding for the show to continue – instead, many of them were appreciative. Despite adoring the characters and the concept, the audience recognised that it was time for people to move onto new projects. Millions of people were heavily invested in House and wanted closure. Some went as far to say that House should not have continued past the sixth series, as it had lost its freshness and sense of humour. Regardless, the show’s commitment to character development gave House a limited shelf life.

The pilot episode was titled ‘Everybody Lies’, a phrase that is uttered countless times throughout the eight seasons that make up this nuanced medical procedural drama; the final episode was appropriately titled ‘Everybody Dies’.

A hospital whodunit with a twist, House’s enlightened cynicism and addictive tendencies made him an endearing character that you empathise with. This series was amongst the most thought provoking and intelligent pieces of television in recent history and there is over 125 hours of it to experience. All told, House was a hugely successful and influential medical drama that deserves to be watched. Even if its ideas are never executed to the same exceptional standard, House’s television legacy will be felt for a long time to come.

All eight series of House are now available on Netflix.