New antibodies could treat dengue fever

Utsav Radia on Imperial research that could lead to the first vaccine

Researchers from the Department of Medicine at Imperial have identified a new class of antibodies that is effective against the virus that causes dengue fever.

Dengue is a mosquito-borne viral infection found primarily in tropical and sub-tropical regions around the world. However, in recent years, transmission has increased predominantly in urban and semi-urban areas leading it to become a major international public health concern with an estimated 400 million infections occurring annually.

Over 2.5 billion people (over 40% of the world’s population) are now at risk from dengue and the World health Organisation (WHO) estimates there may be 50-100 million infections worldwide every year.

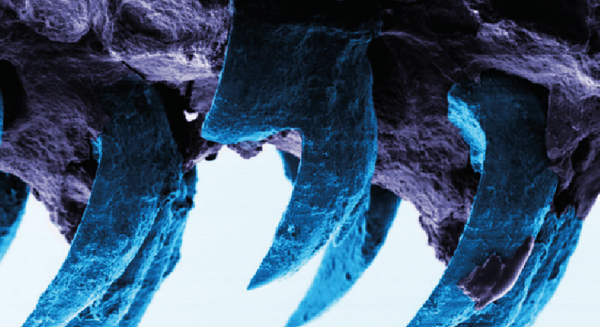

The primary vector of dengue is the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which lives in urban habitats and breeds mostly in man-made containers. Unlike other mosquitoes, Ae. aegypti is a daytime feeder, with the females biting multiple people during each feeding period. Initially, the virus is transmitted from infected humans to uninfected mosquitoes, the virus subsequently incubates for 4-10 days in the mosquito, after which the infected mosquito is capable of transmitting the virus for the rest of its life.

Patients who are already infected with the dengue virus can transmit the infection for usually 4-5 days (max. 12) via Aedes mosquitoes after the onset of symptoms; the virus cannot be transmitted from person to person.

Dengue fever is a severe, flu-like illness that can affect people of all ages, but seldom causes death. It is suspected when patients have a high fever accompanied by two of the following symptoms: severe headache, pain behind the eyes, muscle and joint pains, nausea, vomiting, swollen glands or rash. Symptoms usually persist for around one to two weeks.

Occasionally, dengue fever can develop into a more aggressive form called severe dengue (also known as dengue haemorrhagic fever) which is a fatal complication as it can lead to shock (a sudden drop in blood pressure), bleeding and organ failure. As there is no vaccine as yet for the dengue virus, the best way to prevent infection is using common sense precautions – such as hand washing, wearing protective clothing and using mosquito repellent – whilst travelling to high-risk areas.

The dengue virus has four differnt strains, called serotypes, which are distinguished from each other by their surface antigens. Recovering from infection by one provides lifelong immunity against that particular serotype; however, if an individual were to be infected by another serotype, cross-recognition by the immune system of the other one may only be partial and temporary, increasing the risk of developing severe dengue.

Fortunately, researchers from the Department of Medicine at Imperial, in collaboration with scientists from the Institut Pasteur in Paris, have identified a new class of antibodies that is effective against all four serotypes of the dengue virus. Antibodies are proteins produced by immune cells (B-lymphocytes) that can recognise and selectively bind to specific parts (called epitopes) of foreign objects called antigens.

The binding of the antibodies to antigens on microorganisms such as bacteria and viruses are what help our immune system recognise them as being foreign, so it can attack them and neutralise their harmful effects on our body.

In the study, published in the journal Nature Immunology, the scientists analysed blood samples of infected patients in Southeast Asia to examine the antibodies produced by their immune systems. In the process, the scientists identified a previously unknown epitope, referred to as the “envelope dimer epitope” (EDE) which ‘bridges’ protein subunits on mature virions (the infective form of the virus, as inside the body) and is common to all four strains. Monoclonal antibodies, characterized in the study, to the EDE showed a strong response across all four strains of the dengue virus.

These antibodies could potentially be used either directly in the prevention and treatment of dengue infections or in the development of subunit vaccines that could be used to stimulate the immune system to produce antibodies to the EDE.

In a second paper, published in Nature, the researchers analysed the structure of the antibodies, which forms the basis of developing a vaccine.

Professor Screaton, lead of the study, expressed that “current vaccine trials [for dengue] have shown some promise but do not fully protect from infection…this new class of antibodies points the way for a new approach to a dengue vaccine design which we are pursuing”.

Up till now, there was no specifically directed treatment for dengue apart from paracetamol, replenished fluid intake and resting; this new antibody approach has opened many further treatment avenues for exploration. So it seems like we may not be far off from being able to greatly enhance our armoury in tackling the rising incidences of dengue virus infections and complications in the near future.

DOI: 10.1038/ni.3058;

10.1038/nature14130