Slash and Burn: The Future of British Arts under the Tories

Indira Mallik guides us through the proposed changes to funding for culture under the Conservative majority

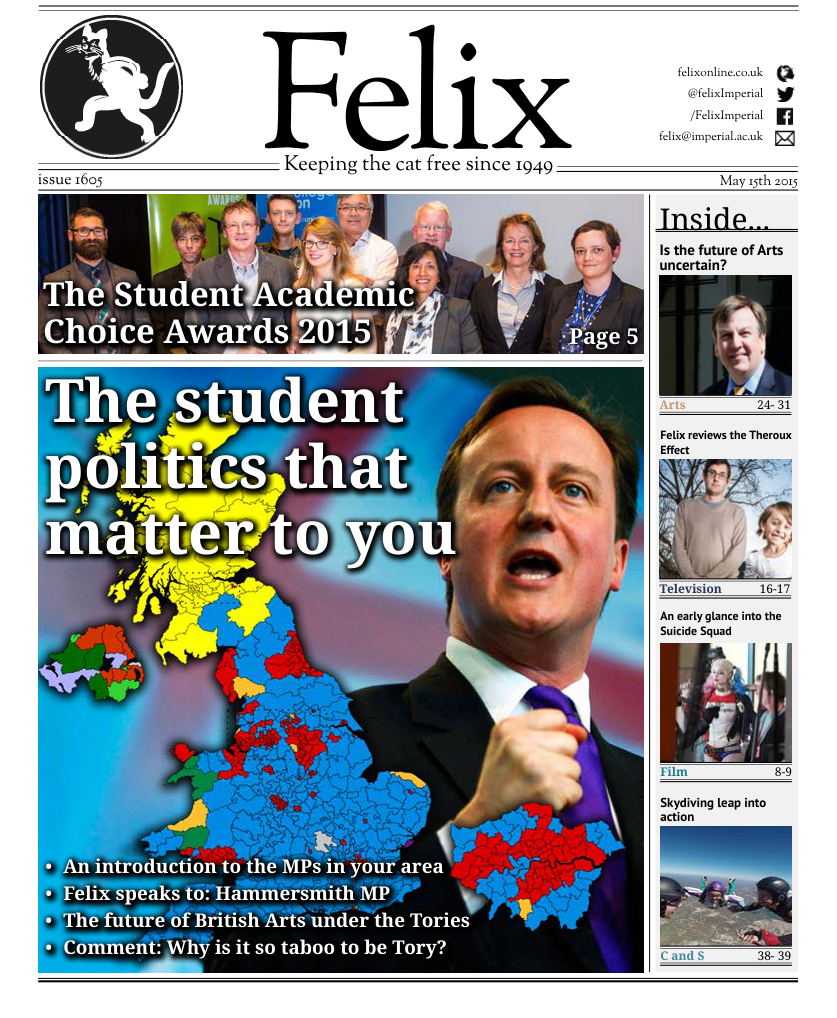

Last Friday, Britain woke up to an entirely changed political landscape. Instead of days of coalition talks, or discussing the constitutional ins and outs of a minority government, we were faced with a Conservative majority. Within the space of hours, the commentators went from discussing the probability of the vote share to the probability of who would end up in the cabinet. On Monday we found out that David Cameron had appointed John Whittingdale as Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport. Already the tabloids have claimed this as “declaring war on the BBC”. Whittingdale has a history of being notoriously anti-licence fee, proclaiming it as “worse than the poll tax”. Despite no doubt ruffling a few feathers at Broadcasting House, the choice of John Whittingdale, who was Shadow Culture secretary and later Chairman of the Media Select Committee, certainly seems to makes more sense than his predecessor Sajid Javid, who by all accounts struggled to convince journalists and the art world alike that we was interested in the performances it was his job to attend.

The Conservatives have pledged to deliver their manifesto in full now they are unhindered by coalition partners, but what does this mean for the arts? Throughout the election campaign, the arts barely got a look in, as the discourse was dominated by immigration and the economy. Likewise, the arts feature in a fraction of the Conservative manifesto, in which the Tories promise to “keep our major national museums and galleries free to enter, support school sport, support our creative industries and defend a free media”. So far, so vague.

The details of this pledge pertain mostly to investing in a “Great Exhibition in the North”, particularly the building of the The Factory, a new theatre in Manchester to which Chancellor George Osborne has already promised £78m. Whilst this is a welcome step towards addressing the long standing bias towards funding London-based projects at the expense of the rest of the country, it worryingly suggests that the The Factory is being pushed as the face of investment into the arts whilst savage cuts are made into the overall arts budget as part of reducing the deficit. In the last government, £168.5m in real terms was cut from the English arts as a whole since 2010, representing 36% of the total arts budget. The funding cuts have forced the main arts funding body in England – Arts Council England – to rely completely on Lottery funds from April 2015 to fund some of its core portfolio. National Campaign for the Arts (NCA) say in their _Arts Index _– the ‘health check’ on arts in England – that over-reliance on Lottery fund will “leave the sector vulnerable [because] lottery income can vary hugely depending on the mood of the people”.

In order to fulfil their pledge of cutting a further £12bn from departmental budgets, the Treasury would have to commit to cuts at the same scale for the next 5 years. In all likelihood, this will lead to the closing of local museums and libraries, cutting off the grass roots level investment that is so vital in allowing the arts to sustain themselves in the future. In November last year, protesters took to the street when the local council in Liverpool announced plans to close 11 out of its 19 libraries. Newcastle-upon-Tyne published a draft three-year budget in 2012, which projected a cut to funding for arts organisations of 100% effective from April 2015. Soon, other councils may follow suit with similarly drastic proposals.

The arts in England are on the cusp of “serious and irreversible damage” caused by cuts to funding, the findings of the 2015 Arts Index have revealed. It further reports that in order to sustain themselves, arts institutions have been forced to raise prices to raise the earned income generated. The NCA says that income raised in this way is soon to saturate “the amount people are prepared to pay for a ticket is limited, and so is the number of seats”, and that higher ticket prices are creating a barrier to access to the arts; a recent study found that though engagement in the arts was higher in the 2013/2014 period, those participating were from higher socioeconomic backgrounds. Reducing access to lower socioeconomic groups creates a barrier towards ethnic diversity too, and in light of the recent proposals to cut funding to arts organisations that fail to increase diversity in their programmes and audiences, the funding shortage risks driving a vicious cycle of exclusion and financial shortfall.

David Cameron proposes to plug this funding hole by asking private parties to step up to the plate. The ‘Big Society’ pledges come directly after the arts pledges in the manifesto, suggesting a growing reliance on private philanthropy and privatisation to sustain the arts in the face of falling government subsidy. This has been the party line for some time now. Back in 2010, the then Culture Secretary Jeremy Hunt said “if you said to me what is the one thing I could do […] that would make a real difference to the arts, I would say it would be to help foster an American-style culture of philanthropy to the arts and culture here in the UK.” Critics of this policy point out that the tax system in the UK does not encourage philanthropy in the same way as the US, where a culture donating to the arts has been built up over decades. Placing all of the funding power in the hands of private philanthropists instead of centralising to some degree such as to Arts Council England poses the risk of supporting only a narrow range of artists, stifling creativity that currently thrives despite being on the peripheries of mainstream culture. Silencing this group of new artists still finding their voice would further reinforce a chronic lack of diversity that has already taken root in this country’s artistic landscape.

More and more, young artists may find themselves relying on charities such as Arts Emergency which seeks to provide opportunities for young people in the arts via inclusion in the ‘Alternative Old Boy’s Network’. Privatisation, on the other hand, has already led to chaos at the National Gallery. When management chose to outsource two thirds of its gallery staff to a private security firm earlier this year, the union representing them, PCS, organised two 5-day strikes. A third is planned if a new pay cannot be negotiated.

These strikes have meant closing off gallery spaces housing some of the most important art in the country – including Vincent Van Gough’s Sunflowers – behind huge black doors; school trips were cancelled, tourists were left disappointed. Citing this example as a possible harbinger of worse to come, Jonathan Jones, art critic for The Guardian, wrote this week that “five more years of Cameron will reduce the arts to a national joke”.

Not everyone is so pessimistic. Newly appointed chief executive of Arts Council England Darren Henley claimed that Conservatives understand the value of the arts, telling The Stage that the Tories had been more supportive of the arts in the previous parliament than they were of many other sectors. Certainly, Labour’s plan for the arts didn’t seem to differ much from their opponents’: when a Tory dossier emerged earlier this year claiming that Labour would reverse £83m of spending cuts to the arts, the Labour press team took to Twitter to simply say “we won’t”.

Although under fire from all sides, the country’s cultural capital is perhaps one of the strongest exports we have. The creative industries generate £76.9bn annually – that equates to £8.8m per hour and accounts for over 5% of UK jobs. Last year, as productivity fell, the creative sector actually grew by 1%. Speaking to The Guardian John Kampfner, CEO of Creative Industries Federation, says “[success in the arts] has not come by accident or in isolation, but is the result of several decades of smart investment and policy-making. To make any further cuts in arts and arts education budgets at a time when we have irrefutable evidence of their economic value (let alone their social value) would be to bite the hand that feeds us.” Jane Webb, director of studies at Manchester Metropolitan University adds “art and design is about changing the world, not just producing more images, objects, or working within jobs that already exist.” The July 2013 report Humanities Graduates and the British Economy: The Hidden Impact conducted by the University of Oxford has found that 80% of all Oxford humanities graduates go on to be employed by key economic growth sectors such as finance, law, media, and education. This is a trend that has been replicated across universities.

The arts are often referred to a ‘soft subject’, which to politicians can too often mean code for ‘easy target’, but the new government must look to the long term when deciding where the cuts should fall. Being too short sighted and caving to the pressure to cut the arts budget in order to protect others may do more harm than good all round according to David Pountney, the chief executive and artistic director of Welsh National Opera, who wrote last month “well-being is not something that can be segmented into physical health alone. A lively mind stimulated and nurtured by cultural experience is one very important kind of health – a kind of health that can inspire and energise a new generation.” He added that unless the government could recognise this fact, the “new generation [could become] the lost generation”.

In a typically eloquent address in the Arts Council England (ACE) Annual Report for 2013-14 published last month, Sir Peter Bazalgette, the Chair of ACE, wrote “we do hear the question asked, “Can we afford to fund the arts?” The answer is simple: “We can’t afford not to”. And the tougher things get the more important our cultural life becomes.” He goes on to cite a 1945 radio address made by John Maynard Keynes, who established public funding of the arts in Britain: “[arts funding is] to replace what the war had taken away”. The case for survival of the arts is has never made more clearly than by Donbass Opera in Donetsk, Ukraine, which remained open to give performances even as tanks rolled down the streets. Deputy Director Natalia de Kovalyova said “tickets were free and there were hundreds of people queuing, we crammed in as many as we could. Two old ladies were in tears, on their knees and kissing his hands in gratitude that he had opened the season”.

Nothing so dramatic is likely to happen here, but there is still something to be said for escaping into art when life seems hard. We should be encouraging people to come together and enjoy and participate in the arts, not starving it of oxygen. Ultimately, the new government has a choice to make; they could view the arts in a purely economic sense in the short term and cut further into the arts budget, or see the arts as an opportunity to invest in the creativity and the talent of its citizens and reap the rewards in the long run. I know which one I would choose.