Do we need electoral reform?

Joshua Renken considers the pros and cons of changing our voting system

The election is finally over. It was a tightly contested campaign but in the end, the Tories carried the day. The final tally put the Conservatives on a slim majority, and sent Labour back to the opposition benches for another five years. The country has moved further to the right, which ironically would bring us closer to Europe, and Miliband will not take the top spot in UK politics.

This election saw the rise of three insurgent parties – the SNP, UKIP and the Green Party. The Scottish Nationalists swept the board in Scotland, winning 56 out of a possible 59 seats and 50% of all the votes north of the border.

But is it fair that half the votes translate to virtually all the representatives? Whatever your thoughts on UKIP, it’s hard to suggest that they only deserve one solitary MP after receiving 3.8 million votes (an eighth of all the ballots cast in the UK). The Green Party also has just one elected Member of Parliament, despite receiving 1.1 million votes.

Two MPs for almost 5 million votes? Is that really fair?

When you look at the average number of votes it took each party to win an MP, you see that the largest parties do well from our current electoral system. The SNP received on average 26,000 votes for each of the seats they won on 7th May. The Conservatives received 34,000. Labour received 40,000 per MP elected, and the Liberal Democrats charted up 291,000 votes per MP. The Greens snagged more than 1,100,000 votes despite only having one MP and UKIP took a staggering 3,800,000 votes, just for Douglas Carswell. Clearly, the disparities are massive. Ever since we found out the results in the small hours of 8th May, people have been debating the merits of a more proportional voting system.

In fact, electoral reform is one of those rare subjects that UKIP and the Greens can agree on. Natalie Bennett and Nigel Farage both agree that first-past-the-post (FPTP) has had its day and is no longer democratic in this new age of multi-party, more continental style politics. The current FPTP system undoubtedly has its flaws, the chief amongst them being that it is not ‘perfectly democratic’, in this case since the number of seats a party wins in the House of Commons is not directly proportional to the number of people that support them. But in reality no system of government can be perfectly democratic.

One of FPTP’s supposed benefits is that it is more likely than other systems to deliver majority governments. For a long time this statement was, broadly speaking, true. It meant that parties with far less than 50% of the total vote could form stable administrations. This is because the amount of power has is not directly dependent on the share of the vote your party wins, but rather by the number of seats where your party can win the most votes.

FPTP works quite well in a two-party system, and has produced a century of alternating Labour and Conservative governments. FPTP also allows constituencies to have a representative that has that area’s best interests in mind.

However, due to the different socio-economic circumstances in each area, many people around the country find themselves voting in very ‘safe’ seats, where one party has a disproportionately large amount of support in the area compared to the rest of the UK. Having safe seats can, and sometimes does, lead to poor constituency MPs that take their seat for granted and do not work hard to serve their constituents. But as we move to this new multi- party political landscape, people are beginning to question its merits.

Parties with a sizeable chunk of the popular vote but a disproportionately small amount of parliamentary representation – such as the Lib Dems, the Greens and UKIP – have a vested interest in changing the electoral system, so that the number of seats each party wins is more closely aligned with the number of people voting for them.

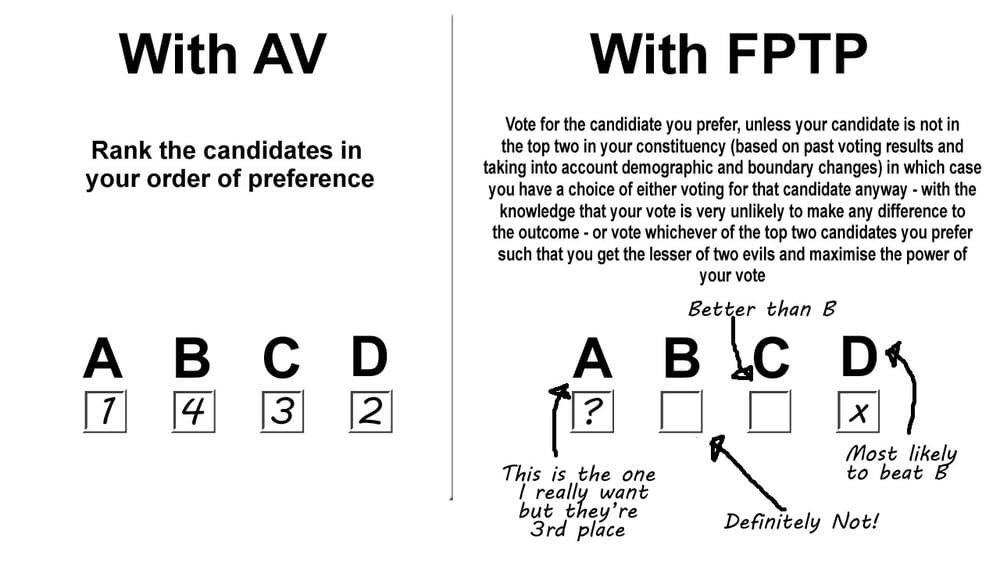

FPTP makes a lot of people feel that their vote is wasted, and many feel that they should vote tactically in order to get the lesser of two evils.

So, what are the alternatives?

Well, in the UK we actually had a referendum on electoral reform just four years ago in 2011.

As part of the 2010 coalition agreement between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats, Nick Clegg negotiated for an Alternative Vote (AV) referendum. In the AV system, voters can rank the candidates in order of preference instead of only putting an X next to one candidate.

Ballots are initially distributed based on each elector’s first preference. If none of the candidates manages to secure more than half of votes cast, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated.

Ballots assigned to the eliminated candidate are recounted and added to the totals of the remaining candidates based on who is ranked next on each ballot. This process continues until one candidate wins by obtaining more than half the votes.

One of the benefits of FPTP is its sheer simplicity. You can explain it in one sentence. “The candidate with the most votes wins the constituency.”

However, the AV system would ensure that the most agreeable candidate wins, by taking into account which of the candidates a voter would prefer to see representing them after their first choice.

The Conservatives and DUP took the official position for a No vote, while Labour had no official party position. Every other minority party was in favour of the change. FPTP benefits the two largest parties the most, so there is a large incentive for all the other parties to campaign for electoral reform.

In the recent election, the Conservatives won 51% of the seats in the House of Commons, but secured only 37% of the popular vote. Labour have 36% of the UK’s MPs with just over 30% of the vote. However, turnout was low (just 42% of registered voters) and the “alternative vote” system was rejected with only 32% in favour of change.

AV is not the same as a full-fat proportional representation “PR” system, which would aim to give each party the same proportion of the power in Westminster as indicated by their percentage of the popular vote across the country.

If the parties’ power were determined solely by their national share of the vote, the Tories would have 240 MPs, Labour 200, UKIP more than 80, Lib Dems 50, SNP 30, and Greens 25.

One of the biggest problems here is that, under this system, parliamentary representatives would not have the constituency allegiances that they currently do under FPTP. It would also make single party majority governments a thing of the past, as we are very unlikely to see a party win more than half of all the votes any time soon.

The UK would be governed under endless coalitions, such as the one we had in 2010-2015. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but it does lead to inevitable compromises and disagreements that typically make the administration quite unstable.

However, the last five years of a Conservative led coalition with the Lib Dems has broadly been a success. The coalition was stable and an economic crisis was averted.

Generally speaking, single party majorities give the government the opportunity to execute their manifestos with conviction, while coalitions can make the public uneasy about backroom negotiations and an unclear mandate.

Personally, I would like to see a single transferable alternative voting system with constituency MPs remaining as our representatives, as this seems to be a reasonable compromise between two of the possible three options. The best of both worlds.

With the increased support for minority parties the debate about electoral reform is likely to raise its head again, and it is likely that there is far more of an appetite for change now than in 2011. If we ever made the decision as a country to move to a PR system, such as the one in Germany, we would be ending our nation’s history of single party majorities.

But these changes would make many who currently feel that their vote is wasted in safe seats more likely to participate in our democracy, as any sensible, repsonsible citizen should. And that, in my view, can only be a good thing.