‘Kings’ of the Jungle De-Throned!

Lauren Ratcliffe on the impact of logging in Borneo’s rainforests

New research in Borneo by researchers from Imperial College London suggests that clear cutting rainforests changes which types of species perform vital ecosystem functions. In logged forests, vertebrates instead of invertebrates appear to be contributing a greater amount to key processes such as seed dispersal and predation. This switch in functional dominance renders these systems more vulnerable to future change.

Whether you be trekking through a tropical forest or taking your dog out for a walk, snorkelling with tortoises or dipping your toes in Cornish waters, in any terrestrial, marine or aquatic environment, vertebrates may catch your eye but most of the time you are the visitor of a primarily invertebrate world. Edward O. Wilson has called them “the little things that run the world,” and invertebrates truly are the movers and shakers of tropical ecosystems, vastly outweighing their more charismatic vertebrate companions in abundance and diversity. One could even call them the true kings of the jungle.

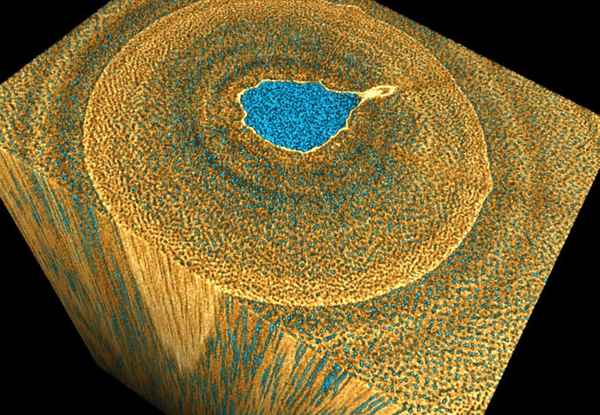

These little critters are the foundations of life across many ecosystems but their importance is most prominent in tropical rainforests. If left untouched by mankind’s chainsaw and caterpillar tractor, beetles and termites, ants and earthworms can go about their business with relative ease and help decompose decaying matter like fallen leaves. Through digestion and egestion, the release of essential nutrients such as nitrates and phosphorous helps fuel the growth of the surrounding fauna. Seeds off trees are carried, munched and dispersed across the forest floor by these little creatures, which helps maintain the vast diversity of tree species. And carnivorous ants and spiders can scuttle about, preying on these insatiable herbivorous invertebrates, thus keeping them in check so they don’t much through all the foliage, dead or alive.

Unfortunately, as a consequence of globalisation and the growing demand from an expanding human population, intense legal and illegal logging currently threatens half of the world’s rainforests. The caterpillar tractors are fired up and chainsaws roar. In particular, the clearing of land for palm oil and timber plantations has rendered Borneo’s rainforest almost unrecognisable, with an area almost the size of Belgium having been cut down between 1985 and 2001 to supply the global timber gluttony. As a consequence of this, these little “movers and shakers” of forest ecosystems have been severely hit, with many species being lost altogether.

So with these integral cogs gone, what happens to the overall functioning of tropical rainforests? Well, surprisingly very little. In fact, new research from Imperial College London’s Department of Life Sciences has indicated that tropical rainforests are actually very resilient to change. What does change, however, are the type of creatures that perform these vital functions. By excluding either invertebrates or vertebrates from patches of both logged and unlogged rainforest in Borneo, the researchers were table to determine their contribution to three ecosystem functions: leaf litter decomposition, leaf-eating invertebrate predation and seed disturbance. The team found that in logged forests, vertebrates played a more dominant functional role and increased in abundance compared to primary (untouched) forest patches.

“Invertebrates are often thought of as the controllers of tropical forests, so it’s surprising that mankind can upset their dominance to this level,” said Dr Robert Ewers, lead author of the study. For example, in pristine primary forests predation on herbivorous invertebrates is almost entirely performed by other invertebrates. However, in logged forests their contribution to this function is cut by 40% and animals such as mice and tree shrews pick up the slack.

Similar trends were seen for seed disturbance rates. However, leaf litter decomposition rates were unaffected by lack of invertebrates and it was not a function taken up by the vertebrates. Instead the team hypothesise that in the altered microclimate in logged forests leading to reduced humidity and increased air temperature as well as altered activities of soil bacteria could have helped decomposition to continue.

Although the ecosystem can continue to function with vertebrates usurping the throne from invertebrates, the rainforests are left more vulnerable to disturbance than before. “The forest will keep maintaining itself, but it will be much more susceptible to further change. Relying on vertebrates is a bad tactic,” Dr Ewers elucidates. “Knocking out one or two invertebrates might not be too bad, as there are many others to take their place, but knocking out one or two vertebrates could now be disastrous.”

Intrinsic susceptibility of vertebrates to a range of human pressures has seen their threat status steadily rise over the last two decades. Increased reliance on them is therefore likely to render these systems more vulnerable to future disturbances. Invertebrates still remain an important actor in logged forests, but as the area of pristine forest shrinks to less than a third of the world’s forest area, their role seems to have switched from true kings of the jungle to jesters of the crown court.