Concepts at a glance: Gender and Sexuality

Madeline and Vin present a guide to the terminology of sexual and gender identity

When discussing gender, sexuality, and similar topics, there are a lot of terms and concepts that you might come across. This article will provide a brief introduction to these concepts, what they mean, and how to use the words correctly. Let’s start with concepts.

Sexuality

This is an intrinsic part of who we are. Sexuality is very complicated; generally it is considered to be binary, but it is actually infinitely more complex. The next-most-simplified model is a spectrum, but this is also a simplification, as sexuality is more like the combination of several independent spectra. In this article we will focus on two components.

The most obvious component of sexuality is the one that expresses which gender or genders you are attracted to; heterosexual (traditionally meaning “attracted to the opposite gender [from oneself]”, though as we’ll explore later the concept of “the opposite gender” is not as well-defined as you might think) and homosexual (attracted to the same gender) are not the only two orientations or identities.

As you may know, there are many more, including but not limited to bisexual (attracted to both men and women), pansexual (attracted to all genders), polysexual (attracted to lots of different genders) and asexual (attracted to no genders; doesn’t experience sexual attraction at all – see below).

The other biggest part of sexuality is the one that expresses the level of attraction, and how you are attracted to someone. This can be defined by how frequently you feel sexually attracted to someone. It’s not the same thing as your sex drive; this is about how frequently there is a person you find attractive, rather than how often you want to engage in sexual activity with a given person.

This includes people who experience ‘normal’ or average levels of sexual attraction to others, often termed verisexual, allosexual or just plain sexual (there’s not yet a consensus on the appropriate term), demisexuals (who only experience sexual attraction to people with whom they already have a close bond), and asexuals (who do not experience sexual attraction at all).

Romantic attraction

These same components can also apply to romantic attraction. This is frequently explained as desire for all the loving, couple-y parts of a relationship, just without the actual sex. All the elements of sexual orientation have corresponding, but independent romantic components.

While it is most common for a person’s romantic and sexual orientations to align, it is entirely possible for them to differ – one common manifestation of this is to be either asexual or aromantic, but there is no reason one couldn’t be, for example, heterosexual and homoromantic (though it would probably suck).

Gender

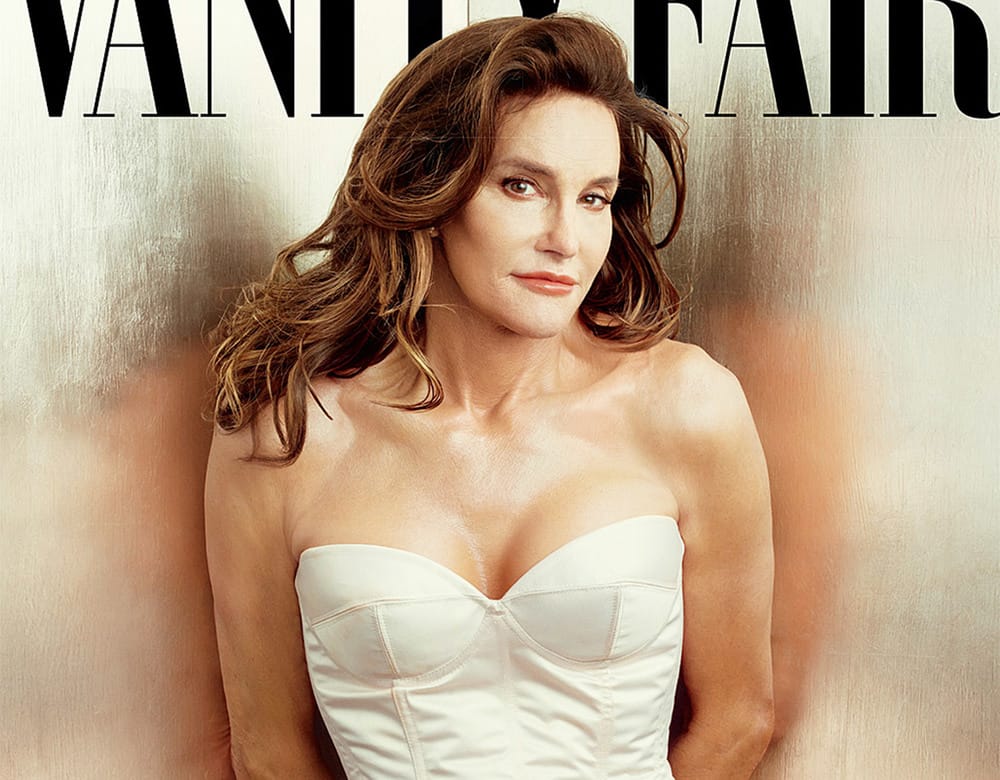

Gender is a nebulous concept which society tends to push as a binary of masculine and feminine, and associated with your sex. However, gender is, to bastardise a quote from the Doctor, more like a great big ball of wibbly-wobbly gendery-bendery... stuff. Gender is expressed in many ways, including hair, clothing and make-up. Gender identity and the gender you are assigned at birth according to your body’s sex do not necessarily match up.

You may be cisgender (you identify with the gender that your body indicates to society), transgender (you identify with a gender other than the one you were assigned at birth), agender (where, similarly to asexuality or aromanticism, gender is a concept to which you feel ambivalence), or any shade inbetween (androgyny is one popular term for the exact middle-ground of the male-female gender spectrum). This is entirely separate from being ‘transexual’ or ‘transgender’ (related but distinct terms; the latter is the more-usually applicable).

‘Transgender’ (always an adjective; please do not use ‘transgender’ as a noun) refers to the situation where the sex and/or gender a person was assigned when they were born doesn’t match their identity. A related term with rather narrower applicability is ‘transexual’ (and while that word has a history as a noun, that history means you should probably avoid using it that way too unless you know exactly what you’re doing), and both are commonly abbreviated to ‘trans’.

These things get more complicated when you consider that intersex people exist. Being “intersex” means their body and reproductive systems do not entirely match either the male or female systems. Up to 1.7% of babies exhibit some degree of sexual ambiguity at birth, and as they grow up these people may end up having any of the above gender identities.

Fluidity

While all these labels are great, if you choose one because it feels right at one point in time, it is perfectly okay (and relatively common) to change it if it doesn’t seem to fit later. A person’s traits can change over time. In recognition of this, some “genderfluid” people exist, meaning that these aspects of their identity are in more constant flux.

Labels

The most important thing about labels is that they’re descriptive, not prescriptive (and certainly not proscriptive). The fact that someone decides that a label applies to them at one point in time doesn’t place a limit on what they can be, but it can be a useful way to convey a set of traits.

The second-most-important thing is that because these things are core aspects of someone’s identity, they have the final say on whether a given label applies. If someone says a sexuality- or gender-related label doesn’t apply to them, it doesn’t apply to them. They know their identity better than you do, after all. Policing someone else’s identity is the height of rudeness.

This is by no means an exhaustive list of concepts or terms, but it is a good place to start. If you’re curious about these concepts, about part of someone’s identity, or are exploring your own, that’s okay, but you need to be respectful in how you ask questions. People don’t have an obligation to tell you things, especially when those things are very complex and intensely personal.

Try to think carefully about your questions and wording, so that you do not offend or upset someone unintentionally. Bear in mind that the people whom you are questioning are first and foremost emotional human beings who have a right to privacy and respect.