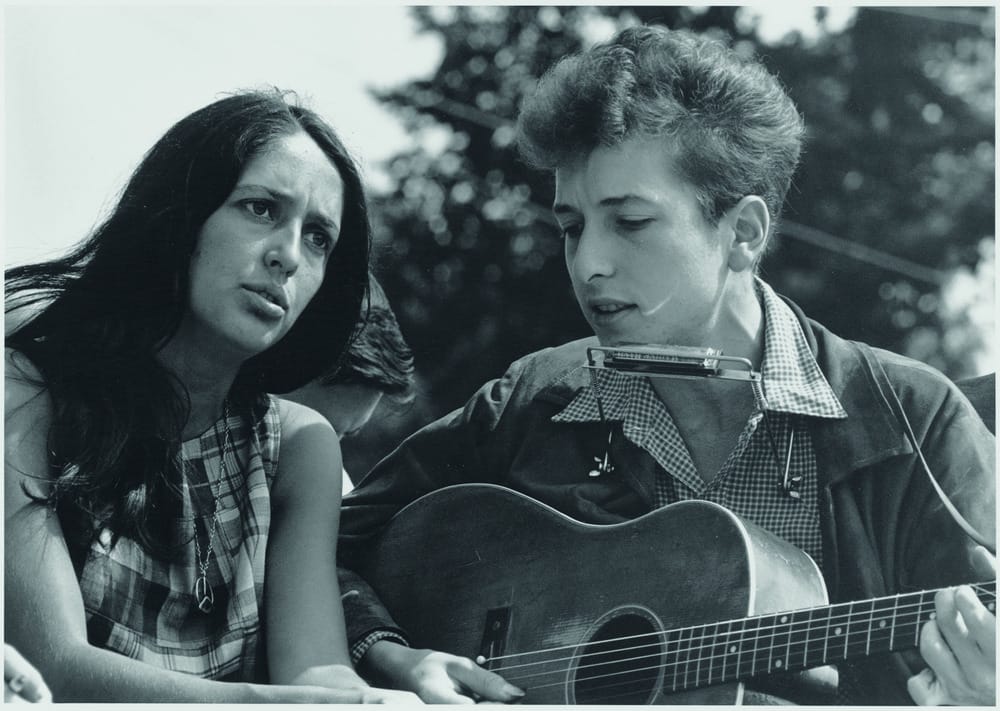

Bob Dylan first musician to win Nobel Prize

Dylan won the Nobel Prize for Literature last week, the first musician to win. Adam Gellatly writes why Dylan deserves to win, and the impact that the songwriter has had on him.

Bob Dylan has never not been a part of my life; his songs were played constantly in my parents’ car and home throughout my childhood. Despite his reputation as a lyricist, it was the sound, not the content of his songs, that I first fell in love with. Positively 4th Street, a single never to appear on an LP, stands out amongst my early Dylan listening. With a plodding piano melody and Al Kooper’s unmistakeable organ playing leading into his voice, it sums up the sound that Dylan was recording in 1965. It was a sound that marked the end of Bob the folk singer and the start of Dylan the rock star, a sound so beautiful that as a 7-year-old you don’t fully appreciate that the song is a rather vicious attack on a former friend. In a similar way to Like a Rolling Stone, there’s an immense amount of anger in his words, but not his voice; for Dylan, the subject matter does not stand in the way of a great song. Once you start to listen to the lyrics, though, my god do the songs take on a new life.

Before Dylan (and the Beatles), the idea that a chart topping musician would sing their own songs was unthinkable

I did so, inadvertently, while doing homework on a winter night in my early teens. I decided to put on the album Bringing It All Back Home; I did this a lot, but normally didn’t get past the first three tracks: Subterranean Home Sick Blues, She Belongs to Me, and Maggie’s Farm. I loved these songs so much by this point that I would always skip back to the start of the album once the third had ended so I could hear them all again. I guess I was distracted by my work and so forgot to do so that particular evening. The album ran. By the time the penultimate track came on I’d finished the homework and started to listen to each and every word. It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding) is, to this day, perhaps the single greatest example of song writing I’ve had the pleasure of encountering. No backing band this time, just the folk singer, accompanied by a harmonica and an eerily quiet guitar, whose simple chord progression changes little over the song’s seven and a half minute run time.

I listened to those seven and a half minutes on loop for the rest of the evening and I’ve been listening to them regularly ever since. Each and every line written and sung by the then 24-year-old stands out. “Darkness at the break of noon”, “Advertising signs that con you into thinking you’re the one, that can do what’s never been done”, “For them that must obey authority…...Do what they do just to be nothing more than something they invest in”, “Money doesn’t talk, it swears”; most lyricists would be prepping a Grammy acceptance speech for having penned just one. Bob Dylan wrote 15 verses of them (oh, and choruses). Bob Dylan isn’t most musicians, he’s a Nobel Laureate.

Dylan’s songs are as great a work of literature as a collection of novels, as much poetry to read as they are songs to listen to

“For having created new poetic expressions, within the great American song tradition” read Prof. Sara Danius, Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy, on the announcement of Dylan’s Nobel Prize in Literature win last week. Right she is, but not only that: he performed those expressions. Pre-Dylan (and pre-Beatles), the idea that a chart topping musician would sing their own songs was unthinkable. Hits were written in office blocks by men in suits and handed to the likes of Elvis Presley for recording. It is fitting then, that Dylan, with 37 studio albums to his name and having reinvented himself constantly over the last 54 years (from acoustic to electric and back to acoustic, from rock to country, from a secular voice to that of a man who has just found Jesus), becomes the first musician to win the prize in its 115-year history.

Much has been said over the past week as to whether the award should be presented a singer at all. Tarantula, a prose poetry book and the first volume of his autobiography, are all Dylan has written in terms of original literature. On top of that his music has been critically acknowledged his entire career (13 Grammy wins and an Academy Award to name but a few), so is there any need to be lavishing him with a prize intended for those who occupy the world of written expression only? Others, however, have argued that his lyrics themselves, published several times, are as great a work of literature as any author’s collection of novels and that they are as much poetry to read as they are songs to listen to. Dylan has not yet spoken publically about his Nobel Prize, despite playing a gig in Las Vegas hours after it was announced. A quote from the man himself, given during a press conference in San Francisco in December 1965, in response to whether his music or his lyrics are more important, is perhaps the best argument one could give for the greatest songwriter of the 20th Century winning writing’s most coveted award: “The words are just as important as the music. There’d be no music without the words”.