Cymbeline

Cymbeline is on at the Barbican Theatre until 17th December

C_ymbeline_ is one of Shakespeare’s lesser known plays. On reading it before going for the production at the Barbican, I could understand why. There is a tangle of plot lines: star-crossed lovers, kidnapped royal babes, attempted seduction, attempted assassination, and topping it all off, a war between Rome and Britain. The inevitable deus ex machina is almost necessary to bring all of them to the happy conclusion.

With this background to work on, it is quite impressive that director, Melly Still, manages to make Cymbeline flow coherently. In the original, Innogen, the only remaining heir of King Cymbeline, marries Posthumus in secret against the wishes of her father, who wants her to marry her stepbrother Cloten. Posthumus is banished to Italy, where he is deceived into believing Innogen has been unfaithful, and orders her murdered. As Innogen flees Britain, a remorseful Posthumus seeks death in the battle against Rome.

Melly Still takes several liberties with the setting, characters and even the lines of the play. She is supported in this by the Royal Shakespeare Company, which certainly lives up to its reputation. I didn’t know Shakespeare had such a sense of humour until I heard the lines brought to life on stage! Bethan Cullinane was especially good as Innogen – her delivery was so natural, it was easy to forget that the lines of dialogue were written in the 17th century.

Much has been made of Cymbeline’s relevance to Brexit and Britain’s slide towards insularity, but for me it wasn’t the major theme of the evening. There certainly was an undercurrent of ‘Britain against the world’ – memorably Cloten’s brash claim; “Britain is / A world by itself; and we will nothing pay / For wearing our own noses.” Meanwhile, Italy is portrayed as a luxurious casino compared to the barren, resource-poor Britain. Just under the surface there is the not-so-subtle question about Britain’s fate; should it decide to cut itself off from the rest of the world?

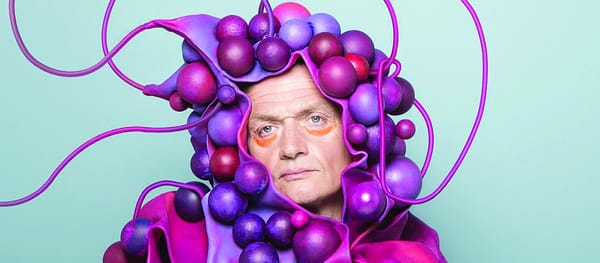

For me, the more interesting facet of the production was its exploration of gender roles; gender-bending is a major feature of Melly Still’s production. This is intriguing in Cymbeline, a play that makes much of the importance of genetics and blood. Shakespeare implies that some qualities are intrinsic – the noble instincts of the long lost Arviragus and Guideria shine through despite their decidedly un-royal upbringing. “How hard it is to hide the sparks of nature!”

What does it mean to be female? Shakespeare is intrigued by this question in the original play. Innogen, though an object of desire for Posthumus, Cloten and Iachimo, must “forget to be a woman” when she cross-dresses as a page boy. In Posthumus’ rant against Innogen, he attributes “all faults that man may name” to women; “Be it lying, note it, / The woman’s; flattering, hers; deceiving, hers; / Lust and rank thoughts, hers, hers…”

In this production, King Cymbeline and his conniving second wife become Queen Cymbeline and a power-hungry duke. Because of our current social norms, a female Cymbeline is perhaps better at portraying the character’s inherent vulnerability as well as Cymbeline’s deep love for her children. Gillian Bevan does an excellent job at balancing this with Cymbeline’s strong side as ruler of a chaotic and divided country. It also made for some amusing lines; in Act III when Cymbeline speaks of Caesar, she declares with a wink: “My youth I spent / Much under him”.

Ultimately though, Cymbeline is a love story, and Melly Still’s production is very much about Innogen and Posthumus rather than the titular character. Bethan Cullinane and Hiran Abeysekera pull off a moving performance of two young people in the first flush of love. When Abeysekera as Posthumus orders Innogen killed in a fit of jealousy, it is the understandable decision of a young man driven mad by passion; the crushing regret and torment he later experiences is palpable.

One does feel at times that the play is trying to do too many things at once, some of which don’t quite work. The Soothsayer, a minor character in the original play, wanders rather gratuitously (and confusingly) in and out of the scenes. Act V provoked a giggling fit in the audience member sitting next to me when little paper men floated down from the ceiling to represent the spirits of Posthumus’ dead family.

This is a playful treatment of Shakespeare’s Cymbeline; an enjoyable production that despite its light-heartedness manages to discuss serious themes of gender and nationalism.