The National Theatre gets its groove back with Amadeus

Amadeus is on at the National Theatre until 1st February

The National’s new revival of its 1979 triumph is one tinged with sadness, doubly so on the evening of its opening. The playwright behind Amadeus, Peter Shaffer, sadly passed away earlier this year, and on the day of the opening the director Howard Davies, responsible for 30 shows at the National over the past few decades, also left us. There is a pre-show appearance by Rufus Norris and Nick Hytner (present and previous artistic directors of the National) to pay tribute to the two men, and there is an undeniable air of melancholy hanging over the building.

It’s an air that lends itself well to Amadeus. This is the story of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart told through the eyes of composer Antoni Salieri, Mozart’s self-proclaimed assassin. From his deathbed, Salieri gives a warped recollection, crying out to the dead Amadeus, begging for forgiveness, pleading for mercy.

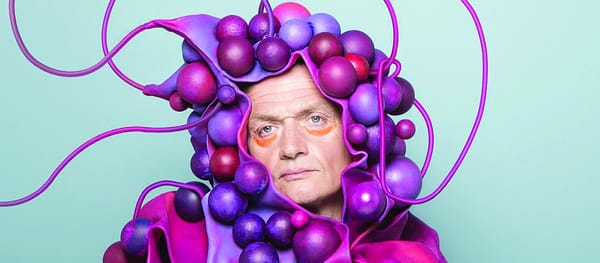

Adam Gillen, playing Mozart, occasionally threatens to overegg it early on. The part as written is an infuriating, childish brat of a young man, so it’s an inherently fine line to walk between hitting the right notes,and just putting everyone off. Early on the performance threatens to become overwhelming; Gillen is a ball of frenetic energy, limbs flying everywhere, his body contorting itself throughout his hyperactive vocal delivery. If maintained for the entire run time, it’s a performance that would rapidly get tiresome. However, as the play goes on, and Mozart crumbles before us, Gillen emphatically lands the pathos of a broken man. It’s heartbreaking to watch; the pain manages to fill the enormous Olivier Theatre – a feat of no small amount of showmanship.

By contrast, Lucian Msamati as Salieri is a model of restraint. The role is less overtly theatrical but nonetheless grabs the audience’s attention. Msamati gives a towering performance. Salieri’s fear of mediocrity, and the intolerable torment he feels as he hears the music of God coming from the pen of a petulant child is made visceral in Msamati’s work. He effortlessly nails Shaffer’s mixture of comedy and tragedy; by turns attracting, and repulsing the audiences, he subtly steals the show without anyone noticing. It’s only in the play’s final moments, with Mozart out of the way, that you realise what’s been in front of you all along. Gillen makes a valiant attempt, but this is Msamati’s show.

The performances are aided wonderfully by Chloe Lamford’s stage design, and Jon Clark’s unobtrusive lighting which mesh beautifully with the play’s themes. It’s all inescapably theatrical; the lighting rigs over stage are clearly visible, many of the sets are simply frameworks for what they represent; curtains attached to bars are neatly tucked away just so to frame the action behind them. The staging underscores the show’s discussion of art and artifice, while also neatly complementing this retelling of events by an unreliable narrator; the dying Salieri.

Vast, and bombastic in every conceivable way (it has a full orchestra in it!), Amadeus still manages to be deeply connecting, and painfully human. It is at once a celebration and a revitalising of Shaffer’s masterpiece; by turning to a past success, the National seems to have re-discovered just what they can achieve. Critically, It’s been a rocky road for Rufus Norris’ tenure thus far (perhaps undeservedly so), but any memories of the underwhelming wonder.land or the lifeless The Plough and the Stars are wiped away by Amadeus. Mediocre no more, the National is back.