A Pacifist’s Guide to the War on Cancer

The Pacifist’s Guide to the War on Cancer is on at the National Theatre until 29 November.

Bryony Kimmings’ latest project might be her most ambitious. A Pacifist’s Guide to the War on Cancer is a poignant portrayal of life alongside cancer, experienced through the naïve eyes of a mother whose baby boy is diagnosed. This sombre premise is transformed with all Kimmings’ charm and idiosyncrasy into a musical, ablaze with physical theatre, acerbic dialogue, and songs such as Even Cunts get Cancer, Fuck This, and MRI RnB. The impressive part of this production is it manages to do all this without becoming crass or disrespectful. In fact, throughout the pantomime a serious point is being raised: cancer is shit and those that suffer shouldn’t be expected to become paragons of positivity – they are as human as everyone else. The best those of us who still live in ‘the kingdom of the well’ can do is to recognise this.

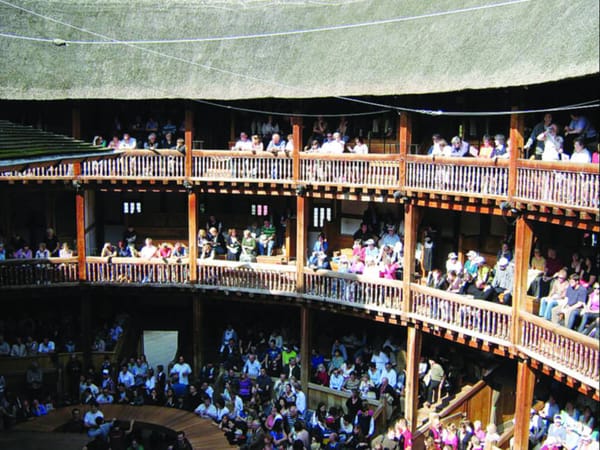

The final scene is intimate and bold, calling forth both actors and audience to share their experiences with cancer

This production is successful precisely because it makes this humanity relevant. The final scene is intimate and bold, calling forth both actors and audience to share their experiences with cancer. Kimmings wrote the play, in part, because of her own experience with a seriously ill son; the characters are all based on real figures Kimmings encountered in her experience in hospitals and with cancer patients. At its most emotive, the actors intersperse dialogue with real recordings of the cancer sufferers they are representing. The research is immaculate and the performances deeply evocative.

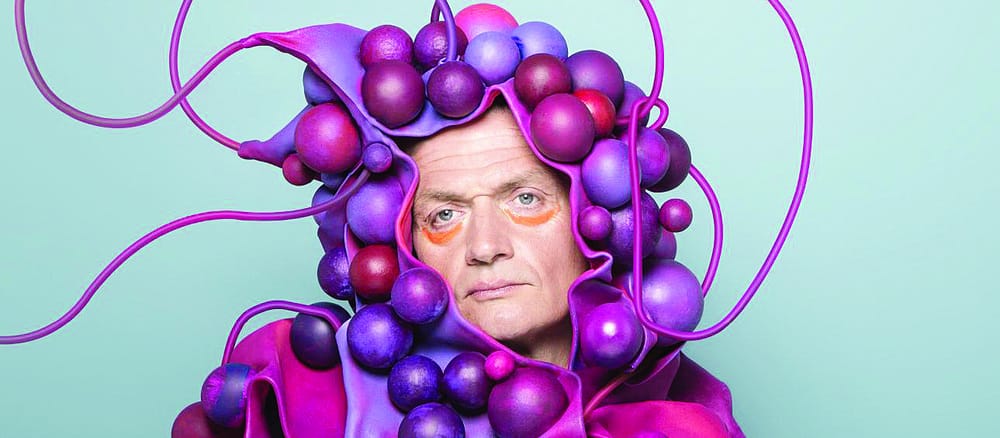

But I don’t love this piece, and I came out of the theatre frustrated by a terrific idea executed sloppily. This is not to say the production isn’t good – far from it. The set design is eerie and atmospheric: a hospital ward with seven exits. The choreography is slick and the band flawlessly moves through an eclectic range of styles. The casting is well done, and on stage the actors form a motley crew of patients and doctors that is visually pleasing, helped by superb costume design throughout. I was especially impressed by the colourful tumour costumes that are surprisingly beautiful (and, to my limited knowledge of cancer biology, surprisingly accurate).

The songs themselves are the play’s undoing: for the most part they are tawdry and forgettable

The songs themselves are the play’s undoing: for the most part they are tawdry and forgettable. This is particularly true in the dull melody of Fingers Crossed, which returns as a motif throughout the play. Perhaps this wouldn’t be as much of a problem if the singing was good, but unfortunately some of the cast were continually sharp and their voices were halting and unassured. I considered leaving this criticism out – after all am I not missing the point slightly? The actors are playing real people, and their voices are accordingly sincere and human. Perhaps, but the arrangements were entirely wrong for this sort of singing; they required trained and powerful voices, the kind that only actress Naana Agyei-Ampdau possessed.

Another issue is the narration Kimmings provides. I understand the need for a narrator in this play, especially after the denouement where the fourth wall is entirely broken and no one seems to know how to continue. Kimmings doesn’t do a bad job either; the narration paces the play well and I liked the dialogue between characters and narrator. At the same time, I have no empathy for Kimmings as she narrates. She researched the play, yes, and undoubtedly has been affected by cancer as almost all of us have, but hers is the voice of a proud writer and it does nothing to elicit an emotional response. It would have been far more powerful if one of the cancer patients upon whom the characters are based had recorded the voice over.

Finally as the older critic sat next to me remarked, the play is heavily focused on millennials. “We don’t talk enough talk about cancer” the narration begins. My neighbour scoffed – given how many people she knew with the disease I’m sure this felt entirely misplaced.

A Pacifist’s Guide to the War on Cancer achieves what it sets out to do: it makes cancer human and it makes it intimate. It’s just a shame that the powerful aspects of this piece clash against its theatricality. Given a re-draft and a change to the song list, this could easily be a five star performance.