Documentary Corner | James Marsh Special

James Marsh is acclaimed as one of the best documentarians working today. Ben Collier takes a look at two of his most famous works, Man on Wire and Project Nim, to latest if the man can live up to all that hype (spoiler: not really...)

I often hear people sing the praises of director James Marsh and his two supposed classics Project Nim and Man on Wire. Having recently seen both films, I thought it would be interesting to present my reviews this week in tandem. The reason for this is that I noticed a lot of similarities in presentation and subject matter between these two films… I also bloody hated one and quite liked the other.

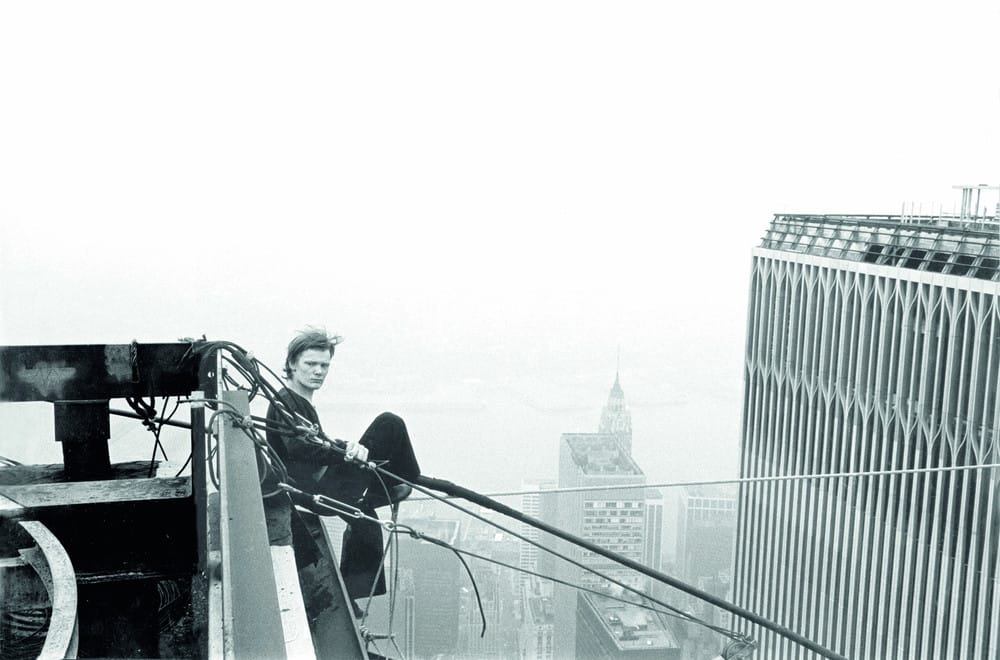

It just so happens that Man on Wire – which fell under the “bloody hated it” banner – was the first of the two I chose to watch. It documents the life of French gymnast Philippe Petit, an eccentric tight-rope walker, most well known for his stunt-walk between the twin towers. Whilst I ultimately see this feat as slightly overhyped, it was undeniably big news in its time and therefore a seemingly good subject for a documentary. Overall, the ‘feel’ of the film is competent enough and the editing is adequate, if lacking a certain energy. The problem with the film is simply its content: unless you like seeing people parroting endless, repetitive praise for two hours, hyping up an event for which there only exists four photographs and is over in five minutes, I wouldn’t recommend it.

The main problem here is Philippe. He comes across as a selfish, self-aggrandising egotist and, unlike in Project Nim, no one featured in the film seems to question what a horrible man he is. For example, at one point Philippe talks about cheating on his long term girlfriend immediately after completing his walk and the story is romantically used to make Philippe seem oh-so passionate and mysterious. Later on, Philippe allows the same girlfriend (along with many friends) to be extradited from the US and cuts contact with them. This act isn’t condemned at all, beyond one of his friends showing a bit of emotion when he talks about quickly forgiving him. With not one dissenting voice in the entire documentary, I am forced to believe that Marsh intended me to root for (maybe even like?) this man.

The recreations of Philippe and his team sneaking their equipment into the towers was initially going to be the one redeeming aspect of this film. However, a quick Google search reveals that almost all of the story was exaggerated or completely made up in an attempt to make Philippe appear more daring and rebellious than he actually was. Whilst I understand the need to dramatize the real world for the sake of an engaging story (The Cove did this well, for example) this part of the film just made me feel lied to. Ultimately, Man on Wire is not the awe-inspiring masterpiece I’ve heard numerous critics describe it as. It’s an overly long, hero-worshipping, and unforgivably boring film about a man who deserves absolutely none of your attention.

I think it’s time for a bit more positivity. Pleasingly, the 2011 feature Project Nim, also directed by Marsh, succeeds in a lot of places that Man on Wire fails. The documentary describes a controversial study from the 1980s, which investigated whether a chimpanzee (Nim) could be taught sign language and communicate with humans. When the project ends in failure, Nim finds himself in ever direr situations before dying at a very young age.

It is the experiment itself, run by Dr Herbert ‘Herb’ Terrace, that makes up the bulk of the running time. Manipulative and selfish, Herb is almost as unlikable a character as Man on Wire’s Philippe Petit: beyond merely his character, Herb’s experiment – which seemed to take a back seat to Herb sleeping with all of his students – is ultimately presented as pseudo-scientific nonsense. The idea of taking a baby chimp from his mother and entrusting a clueless, upper-middle class hippy family to then teach it sign language during adolescence is a wholly pointless scientific endeavour in my eyes. What’s important here is that there is a difference in how Herb (in contrast to Philippe) is presented to us by the director. Where Philippe was showcased in a romanticised light and talked about exclusively by his hero-worshiping ‘friends’, Herb – and his experiment – are actually challenged. He isn’t free from scrutiny as Philippe seemed to be, allowing the film to focus on an unlikable man and have it not ruin the experience. I, for one, actually loved to hate him.

I felt a similar way towards Nim’s first human ‘mother’ Stephanie LaFarge. In our first act we see a lot of Stephanie raising Nim like a human child in her bourgeois-bohemian New York mansion. What’s different about Stephanie is that she is so ridiculous, indulgent, and stupid that she doesn’t even require any runtime being set aside for criticism. Anthropomorphising her little ‘child’ constantly, Stephanie at one point speaks about trying to smoke weed with Nim and even discusses sexual tension between the two… I wish I were joking.

In most other aspects the film is perfectly passable. The post-production job here was obviously monumental, and the filmmakers did well to establish a steady pace and coherent story line. Just as a little aside to finish on – I wasn’t a fan of the fact that all the interviews took place in front of generic grey background. I have always considered it much more effective when documentarians film their subjects in somewhere more personal to their interviewee. Fictional films do not have a monopoly on the use of mise-en-scène, and by choosing interesting and personal locations we can often gain an understanding of characters. Since characters are the driving force in these two films, it’s a small change that would have added a lot.