A fantastic display of failed potential

The Young Vic presents an inspiring but shallow take on a Hindu classic

I really wanted to like Battlefield. Usually, a statement like this foreshadows ruthless panning and heartless criticism, especially when it makes an appearance at the beginning of a review. But I shall try and be objective.

Battlefield is essentially a retelling of the epic poem, Mahabharata, something of a cornerstone of Hindu mythology. The poem is one of the oldest works of literature in recorded history; bits of it date to before the origins of London some two-and-a-half millennia ago. It is by far the longest literary work, a whole order of magnitude above the Illiad and Odyssey combined. It is also a text of considerable importance – historians (notably, W.J. Johnson et al.) argue that it is comparable to the Bible, Qur’an, or the works of Shakespeare and Homer.

Let me get it out of the way: Battlefield is a great production. The Young Vic itself is a remarkable venue, “bustling and unorthodox” and “South London’s glorious temple of leftfield theatre”. It ticks all the boxes – fancy bar (nutritious spring water on tap), a simple, minimalistic black box layout. It’s is worth a visit; few places are as brimming with energy. Their productions are top-notch, and great credit has to be given to whoever it is who oils the cogs and wheels in this machine. Seats are worth their price, things start and end on time, and there are no backstage brawls between stage-hands and makeup artists.

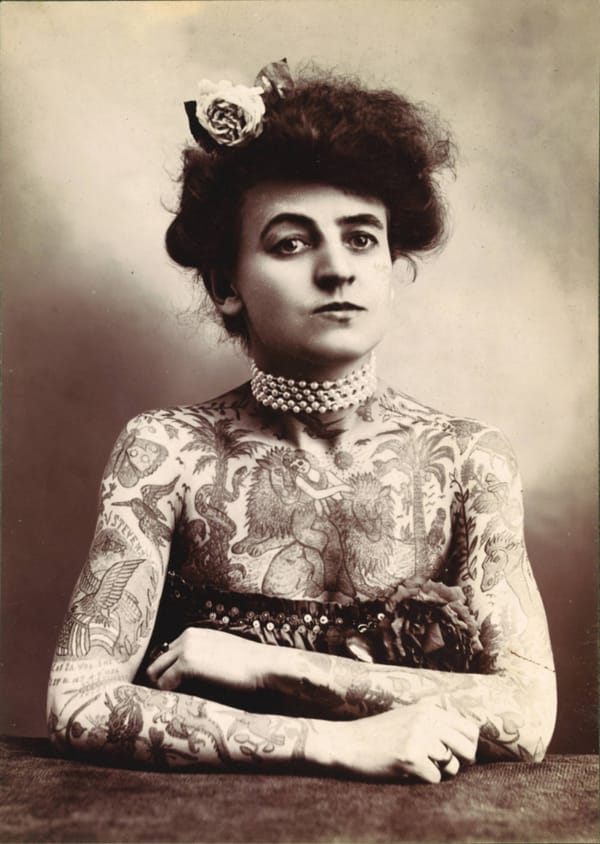

Secondly, Battlefield is superbly acted. McNeill makes a great, relatable everyman of the demigod-like protagonist, Yudishtira. Karemera was great as the female lead, Yudishtira’s mother, an absolute paragon of all that is motherly and matronly, equal parts nurturing and authoritative. I cannot leave out her poise, her grace, and how superlatively she conveys a sense of quiet fortitude with her sheer body language. O’Callaghan is the real stand out though; his primary role as the blind king, the father of a hundred dead men, is deliciously realised with almost Grecian pathos. Finally, Nzaramba plays Krishna, one of the most revered characters in the mythology, whose very essence is his virtuosity, authority and godlike status. Nzaramba is a very, very good actor – with a superb command of expression, intonation, and subtle inflections that he uses to his advantage to create an entertaining performance. But as to how far he embodies the properties of his character, I am not sure. Well, this is the entire cast – sparse, nuclear, four-person. And at the helm of it is Marie-Hélène Estienne and the legendary Peter Brook himself (whose first production of the play ran for a bladder-boggling nine hours).

A potent scene is too often quelled by a visual gag

However, I was less than impressed with Battlefield. I’d definitely say that it falls short of its lofty ambitions, or even cast doubts on the loftiness of those ambitions. The biggest disappointment was the writing – how much more this play could be! The script barely addressed the central plot or, indeed, the most pervasive theme in the source material – namely, war. It was as though one had adapted Sun Tzu’s The Art of War and focused entirely on terrain analysis and taxation. It’s not that I demand blood and violence on stage. It’s that one of the central efforts of the source text is a meditation on conflict and the moral philosophy of justice, killing, and warfare. And instead of this, we are treated to a bunch of fables about snakes, pigeons, falcons, worms, and mongooses. One gets the feeling that the makers of this play abandoned the deeper points made by the work to focus on throwing together a bunch of colourful, exotic parables that would conjure up the peculiar allure of the ‘mysterious East’. What of the interesting character dynamics, the incredibly potent plot, the ruminations on duty, responsibility, and ethics? Instead, we get a funny story about a worm that doesn’t want to die. It is as though a Homerian plot were condensed into a series of Aesop’s fables.

In this way I felt as though the source material was terribly underused. As W.J. Johnson says, this is a text with equivalent literary value and emotive force as the Greek tragedies, or of Shakespeare’s. How it would have benefited from a similar treatment! If only the writers and directors had the courage to delve into the deep melancholy of it all, the heightened drama, the nuances of plot and language – the beautiful writing is all there! But the effect of a potent scene is too often quelled by a visual gag in the following moments.

And this was the other thing – only too frequently a decidedly somber moment in the story would incite uproarious laughter – something that would be entirely jarring and out-of-place in a serious Shakespearean tragedy, which is essentially what the source material is, at least much more than it is a comedy sketch. Maybe my only fault is that I have read it.

But let us not dwell on what could be. What is, is a delightful, comical, entertaining play, to anyone who sees it with fresh eyes. If you have read the source material, however, then you might be disappointed at how poorly-realised its potential is.