Going back in time on the Electronic Superhighway

The landmark exhibition brings together 50 years of art and technology co-evolution

The phrase ‘electronic superhighway’ has become, a mere 40 or so years after it was coined, no more than a vague anachronism. The concept, envisioned by artist Nam June Paik in the mid-70s, has fast become a relic of the bygone age of utopian technology. While Paik’s idea of a communication revolution that has become so far-reaching as to become, in his words, ‘a springboard for new and surprising human endeavors’, modern technology has instead brought with it the threat of coercion, manipulation, and ever-present surveillance. While such an optimistic view of human endeavors has since been consigned to the growing pile of historical disappointments, the Whitechapel Gallery is unafraid to take a retrospective look at the concept. Indeed, it forms the name of its newest exhibition, which looks back at the past 50 years of interaction between the artistic and the digital; the phrase’s ethos is reflected in this retrograde collection of work, which is exuberant, ground-breaking, and wholly revolutionarily.

As first impressions go, it’s a bit of a surprise. The Whitechapel have taken the (as far as I know) unprecedented decision to arrange the exhibition in reverse chronological order, and the result is something that is an exhibition striking in its immediate familiarity. For most retrospectives, be it of Caravaggio or Caro, the collection will take a strictly normative chronological route; the result is an exhibition that tends to be most familiar in its centre, where artists reach their creative peaks, sandwiched between early periods of juvenilia, and later works that simply seem outdated. In contrast, the Whitechapel exhibition begins with what is most relevant and familiar: artworks produced in direct response to the needs and pressures of the modern age.

This collection of work is exuberant, ground breaking and wholly revolutionary

Thus, we have Amalia Ulman’s four-month long project Excellences and Perfections, perhaps the first piece of performative art produced entirely through the medium of Instagram, and Mahmoud Khaled’s staged conversation Do You Have Work Tomorrow?, which transforms the virtual social space of Grindr to a physical, temporally-isolated reality. The interplay between the promise of increased connectivity social media brings, and the isolated actuality, it a running theme. As we move back in time through the exhibition, the references in the work become more and more dated, and the technology used cruder; eventually, we reach the last room, where Peter Sedgley’s circle works appear to shift before our eyes due to the changing lighting, and a poster for the ICA’s Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition questions the new shifts technology will bring to the art world – a seismic change that we have just surveyed in the previous galleries.

Of course, such a concept would be mere window dressing if the work inside weren’t any good. Luckily for us, the curators at the Whitechapel have managed to put together a cutting and incisive show, a wide-ranging retrospective of the last half-century, which will surely go down as a landmark exhibition.

From the off, we are introduced to artworks whose themes, while possibly synonymous with modern life, have their roots within the advent of the technological revolution. The nature of the cyborg, omnipresent in popular culture since the 1960s, is explored in Aleksandra Domanovic’s work, which uses the ‘Belgrade Hand’ – the first artificial hand with five fingers – to examine the relationship between man and machine. Elsewhere we have mediations on the theme of representation in the virtual world; in a society where our self-representation is primarily made up of online data, the disturbing, dizzying video works of both Ryan Trecartin and Jacolby Satterwhite show us the self-empowerment of creating our own narratives.

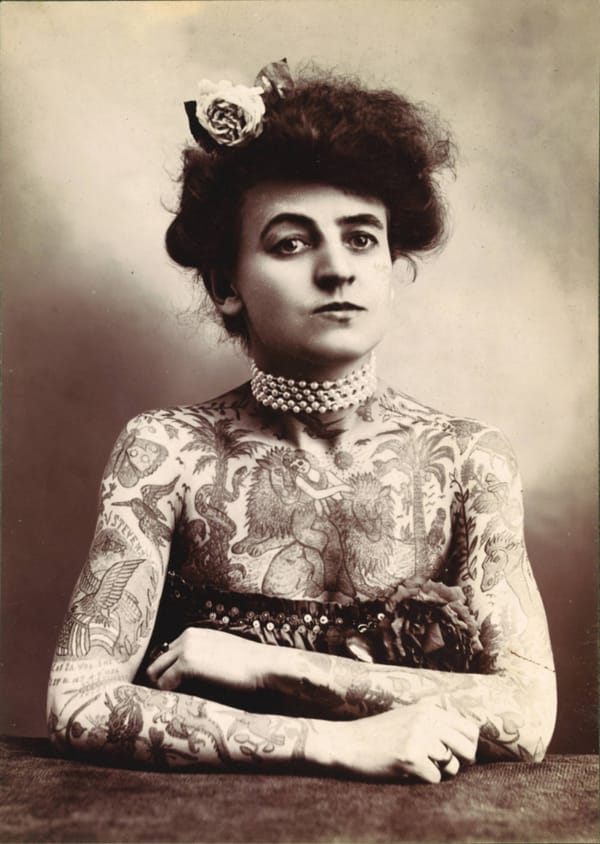

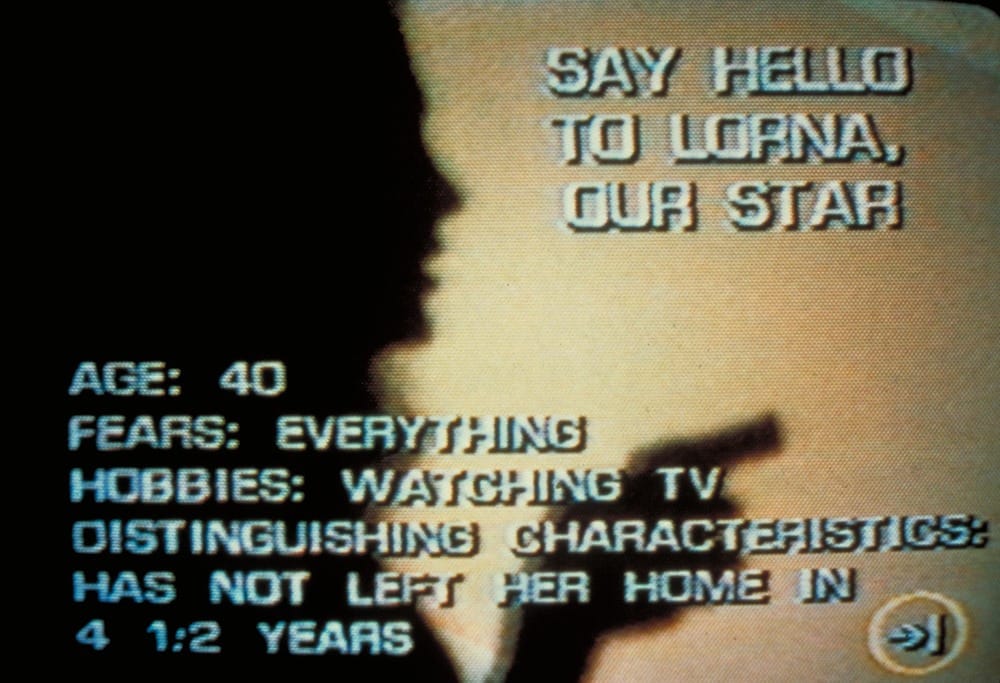

This theme of narrative control is echoed in earlier works, such as Olia Lialina’s 1996 work My Boyfriend Came Back from the War, and Lynn Hershman Leeson’s seminal interactive work Lorna. The latter tracks the decisions of an agoraphobic woman, while the former explores the relationship between a distant couple after an unnamed conflict, resulting in a mosaic of hauntingly black screens. The depressive nature of both is a bold contrast to the exuberant works exhibited towards the beginning of the exhibition. Nam June Paik is given a near-obligatory mention with his multi-screen assault Internet Dream; but while personal self-expression may have fulfilled his prediction for a playful, liberating world of technology, it has come at a price, and the more contemporary pieces belie a sense of creeping encroachment of civil liberties.

His piece allows visitors to hide their movements through use of an encrypted Wi-Fi signal

Trevor Paglan’s map-based work traces the cable-routes through New York, juxtaposed against the NSA’s famously-blocky slideshows, while his piece Autonomy Cube allows visitors to hide their movements through use of an encrypted Wi-Fi signal. Elsewhere, James Brindle, coiner of the New Aesthetic, provides the most directly cutting piece in the exhibition with Homo Sacer, a facsimile of the annoyingly-chirpy, happy-valley-esque human holograms found in airports that quotes lines from UK legislation, warning visitors with the threateningly bureaucratic claim that ‘citizenship is a privilege, not a right’. The addition of Addie Wagenknecht’s Asymmetric Love, a chandelier of CCTV cameras that hang over the room, is a playful work, but has all the nuance of a Banksy piece.

Never fear, resistance to erosion of civil liberties is at hand. Douglas Coupland defies Facebook’s facial recognition system by replacing visages with Mondrian-esque blocks, echoing designer Craig Green’s plank masks; Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s Surface Tension, a giant eye that follows the patron round the gallery, allows us to confront the usually-indelible forces of surveillance; and Zach Blas’ work joyfully subverts both the heteronormative nature of internet technology, and the force of unfettered capitalism propelling it.

“Electronic Superhighway” may seem like an anachronistic phrase, and indeed, many of the pieces displayed in the exhibition attest to the faster-than-light nature of internet trends. ASCII art, early web interfaces, and scratchy live-TV broadcasts are all dragged out of the broom closet of technological history, and brought to the forefront. Cory Arcangel’s work, which sees an Instagram post of Paris Hilton overlaid with a MySpace ripple effect, brings the world of the modern and the recently-obsolete crashing together, making us wonder whether the hegemonic grip Facebook et al have on internet space is truly unbreakable.

But while the phrase itself may be a blast from the past, the show is anything but. Electronic Superhighway displays the dazzling array of ways technology has informed art, and provides us with a cautionary hope for the future, as artists form the vanguard of a movement leading us into a brave new world.

Electronic Superhighway is at Whitechapel Gallery till 15th May.