Hollywood and the DuVernay Test

Ava DuVernay has supported a new test to encourage wholly developed minority characters in films

For the second year running, the Academy Awards has nominated only Caucasian actors for the awards, igniting a powder-keg on social media, and highlighting the lack of diversity in the film world. But not all hope is lost; while actors like Charlotte Rampling and Julie Delpy may make misguided comments on the industry, there are signs of real change: Cheryl Boone Isaacs, president of the Academy, has stated a move towards changes in the membership policy, which would hopefully lead to a more representative group choosing the winners; Idris Elba picked up two SAG awards, in a pointedly-diverse ceremony; and the deliberately-titled slave rebellion drama Birth of a Nation has won two of the top prizes at Sundance.

In an article for The New York Times, chief film critic Manohla Dargis has floated the idea for a ‘DuVernay Test,’ one modelled on the Bechdel Test, and named after Ava DuVernay, the director of Selma, whose snub at the Oscars was seen as a crucial indication of Hollywood’s problem with minorities. DuVernay herself has endorsed the idea on Twitter, although the actual form of the test is unclear; while the Bechdel test merely requires there to be two named women characters who speak to each other about something other than a man, Dargis just stated that the test would involve: ‘African-Americans and other minorities having fully realized lives rather than serve as scenery in white stories.’

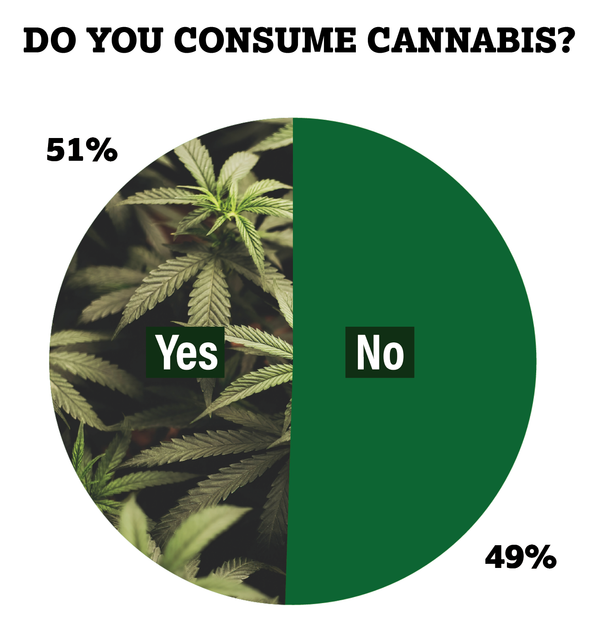

I am sure that there are those who will – like critics of the Bechdel Test – argue that such motions are merely ‘painting by numbers,’ and wouldn’t be in any way representative of the quality of the film. I would say that such critics have obstinately missed the point of such tests: in a US population that is 51% women and nearly 40% non-white, we should expect minority and women characters to serve as more than just a backdrop for the exploits of a (white, straight, male) hero. The test is not about quality, more about the representativeness of the industry.

The DuVernay test, as expressed by Dargis, brings up two key points. The first is that minority characters in films have ‘fully realized lives,’ an idea that involves the characters being named, their thoughts explored, and their portrayal on-screen being nuanced. There is the long-running trope of the black character being the first to be killed in a horror movie, of the Asian character being a maths and science whiz, and of Middle Eastern actors inevitably playing a string of ‘terrorist’ roles; but tropes are tropes for a reason, and they reflect the lack of fully-developed characters offered to minority actors. In one episode of Aziz Ansari’s lauded Netflix sitcom Master of None, struggling-actor Dev refuses a role that would require him to put on an Indian accent, despite the fact that he was born and grew up in the US – it’s a common problem many minority actors face.

You can't win awards for roles that aren't there

Even in those roles where minority actors have garnered acclaim, the range of such roles has been limited: the first black winner of an Oscar, Hattie McDaniel, won for playing a ‘mammy’ stereotype; the last three black winners of the Best Supporting Actress Oscar have won for, respectively, a slave, a maid, and an abusive mother reliant on welfare. While Birth of a Nation does, I am sure, deserve its critical acclaim, it would be fantastic to see roles for minority actors that break out of traditional tropes.

But there is another issue at hand here that the DuVernay Test brings up, not equality of outcome, but equality of opportunity. It is all well and good getting annoyed with the Academy, but really what we should be doing is questioning and examining the deeper power structures present in the film industry. In order to have more minorities being recognized for their work, they need to have the chance of showing off their talent in the first place, something that does not seem to be happening within the current studio system. Often, executives have given the excuse that stories about minorities or women simply don’t sell. This is clearly a lie, as recent releases have proved: Straight Outta Compton made more than $200 million, while Star Wars: The Force Awakens, whose two protagonists are black and a woman, became the highest-grossing film of all time in the US. There is now no excuse for studio executives to refuse to fund minority films on the excuse that it doesn’t represent a safe investment.

Furthermore, many roles that may be filled with minorities are ‘whitewashed,’ with Caucasian actors chosen instead. While we may want to kid ourselves that we have left such portrayals like Mickey Rooney’s grossly-offensive turn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s in the past, we only need to look back a couple of years, to 2013’s The Lone Ranger in which Johnny Depp plays a Native American character, to see such practices are alive and kicking. Depp received a fair amount of kick-back for his choice to portray a Native American, and claimed that he believed he had Native American ancestry; this has not been proved.

The theory of evolution suggests to us that change must be gradual, incremental, and natural, but the rate at which Hollywood is adapting itself to its market-demographic is achingly slow; despite how much the industry may will it, the USA isn’t a homogenous clone-world filled with thousands of Ryan Goslings and Emma Stones. The film industry is sick. While we should rightly criticise the Academy for their refusal to include actors like Idris Elba or Will Smith in their list of nominees, what the DuVernay Test would do is shift the attention back towards the root of the problem: the channels of money and power that flow through the Hollywood studios. There are few roles out there for minority actors, and all-too-often they are shut out of potential roles in favour of white actors, who offer a more ‘bankable’ alternative.

In her emotional Emmy acceptance speech, Viola Davis said that "the only thing that separates women of colour from anyone else is opportunity. You cannot win an Emmy for roles that are simply not there." We should be angry at the industry’s refusal to promote minority actors, not only during awards season, but throughout all stages of film production. What we see when we look at the list of nominees for the Oscars is the tip of an iceberg of inequality. Tests like the DuVernay Test help shed light on this, and set out a new path for the future.