Scientists need to start caring about politics

Forget ISIS or Trump, apathy is the greatest threat to democracy

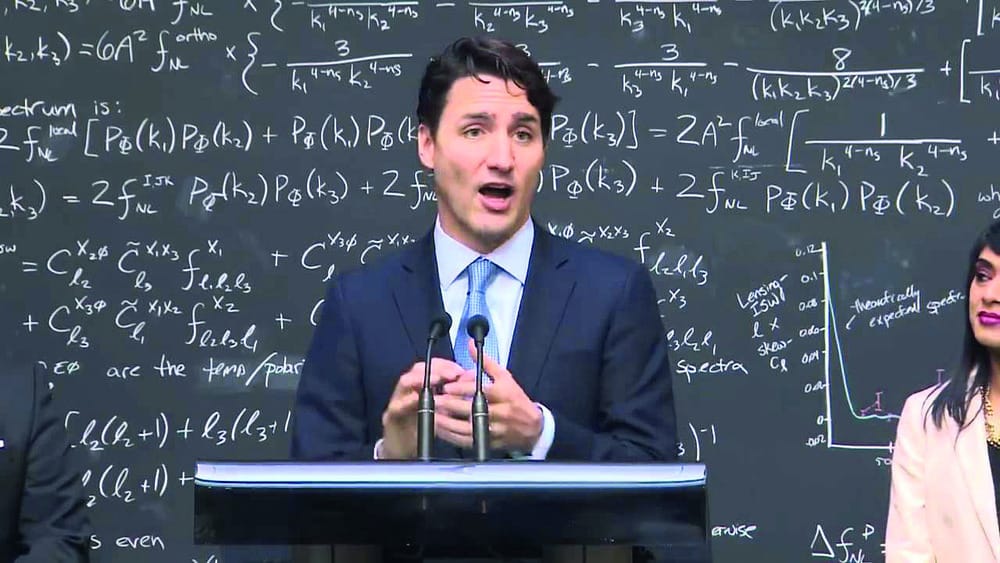

The recent election season has got me in the political spirit, and I have been reminded of the shameful situation that continues to both bemuse and inflame me: the Science and Technology Select Committee. This grand, administrative behemoth, whose expansive remit covers everything from big data to genetics, with its cross-party composition and its inquiry-laden legislature, sets the national agenda on science policy. In a world where science policy is of growing importance, occupying all the top spots on international issues, be they climate change or viral pandemics, the UK Government needs to take leadership and forge the path to a sustainable future.

But fear not, for who should chair the Commons Select Committee for Science and Technology? None other than Nicola Blackwood, an esteemed parliamentarian with a doctorate in – wait for it – musicology. It sounds like something out of a Mitchell and Webb sketch, only the reality is far less funny. Indeed, of the eleven MPs that comprise this essential facet of Government, only seven have graduated from a university and a whopping four have a science degree.

This probably doesn’t surprise you; the British Government’s lack of scientists is not news. The last time I recall a scientist being involved with politics, it was 2009, when Professor David Nutt was sacked after publishing a scientific paper into the social harms of illicit drugs. This not only demonstrates the anaemic quantities of scientific rationale in government, but that no major scientist has taken the political stage for seven years.

For once, perhaps, this second point is not down to faults of the government or an incompetent politician, but is a sad reflection of a global scientific consensus: political apathy.

Maybe it is the lack of objectivity that comes with policymaking, or the narrow-focused research mind-set that is instilled in students from the start, but the trend is clear: scientists don’t care.

Even here at Imperial College London, an institution with some of the sharpest young minds on the planet, we have a student Labour Party Society that was almost shut down last year due to a lack of members (and committee), and our own student think tank that no one has heard of. There are plenty of reasons why Imperial students might be less politically active than our university counterparts, but explaining away our predicament does not solve anything.

With the possible exception of the aspiring bankers, Imperial students are entering careers whose funding and regulations are governed by people who couldn't tell you the difference between a proton and a protein.

No major scientist has taken the political stage for seven years

So why haven’t our science and technology industries collapsed into pandemonium? Well, fortunately, some our MPs became painfully aware of this gaping qualification gap, and so set up the Parliamentary Office for Science and Technology (POST) back in 1989, to research and brief MPs on scientific issues of the day. Initially staffed by one researcher, the humble institution represented how small the realm of science policy was but a mere 30 years ago.

But much has since changed, and today POST has a larger executive board than the entire Commons Select Committee for Science and Technology, its own Fellowship programme and briefs both Houses of Parliament.

Many do not have a problem with this set up, but the fact that we have to introduce an undemocratic institution to compensate for the shortage of scientists in parliament speaks volumes. Few in this country have the scientific know-how to understand the implications of the UK’s science policy, and those who do, don’t vote. This is not just a British problem; global science policy increasingly relies on a few voices of undemocratic research organisations for guidance. These views do not represent broad national perspectives and instead hide behind the veil of objectivity at the cost of our democracy.

As our species makes strides in science and technology like never before, we need now, more than ever, a democratic machine to fairly govern this new world. We need a parliament properly armed with scientists, a population ready to criticise them and a national voice prepared to debate them. Instead, we are sleepwalking into technocracy, bestowing control of the fastest growing and increasingly important policy area on unelected, faceless institutions.

Apathy has consequences. Scientists and students alike have long been silent voices on the political stage, and as a result, governments have turned elsewhere for guidance. Whilst it may be easier to try and opt out of the system, become disenfranchised and complain that it's all rigged, it is vital that you find the courage to engage head-on with democracy whilst we still have it. Citizenship is not a part-time job; if you’re unhappy with policy, at any level, write to your local councillor, visit your MP, or best of all, reflect your dissatisfaction at the ballot box. If you don’t engage, politicians won’t try and win you over.