Cosmic dust hints at alternate history

We couldn’t find a micrometeorite, so here is the cosmos instead.

At the end a of white-washed hallway on the second floor of the RSM building, Dr Matthew Genge has been unlocking the mysteries of the universe through his research on micrometeorites – otherwise known as cosmic dust. Last week however, Genge published a paper in Nature which opened some doors to understanding Earth’s secrets, and has potentially turned some age-old scientific theories on their head.

It’s commonly thought our early atmosphere had little to no oxygen, and was mostly carbon dioxide like the choking atmospheres of Venus and Mars are now. However, 2.4 billion years ago, in the Great Oxygenation Event, ocean bacteria began multiplying and heavily breathing,, bringing our atmosphere to the familiar, comfortable level of 21% oxygen.

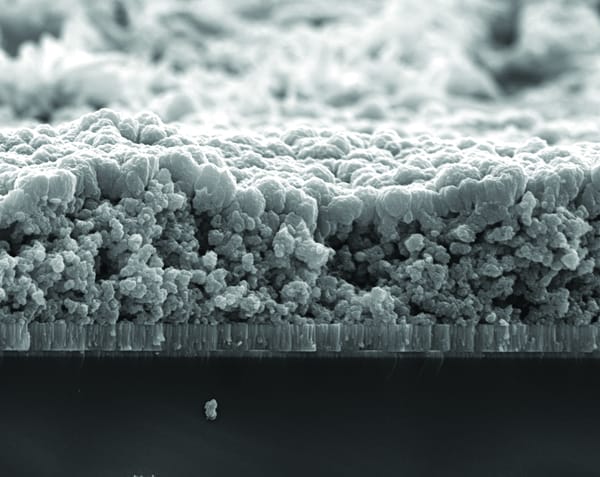

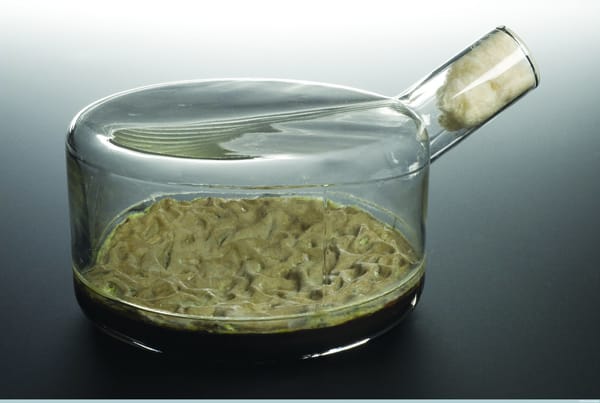

This accepted view is now challenged based on the discovery of 60 micrometeorites found in the arid Pilbara region of western Australia, dated at 2.7 billion years old, 300 million years before this oxygenation event. These tiny rocks were found to contain iron oxide, which had been transformed from traces of metallic iron. This elemental change must have required high levels of oxygen which the comet was exposed to as it fell through our atmosphere. These levels though are not supported by our current theories on the earth’s early atmosphere.

After studying the dust and running mathematical models, Genge and his team realised the data unavoidably pointed to an oxygen rich atmosphere. As all previous research supported the theory of oxygen-starved lower atmosphere, it was time for Genge and his colleagues to think differently about early atmospheric composition: “We looked at the data in the papers saying oxygen was very poor in abundance at low altitude, and we couldn’t fault it –that looks as if it’s true. Our data looks as if it’s true that there’s lots of oxygen in the upper atmosphere, therefore we need to come up with a way of separating the lower and upper atmosphere.”

Based on the evidence in the cosmic dust, the scientists theorised there must have been an oxygen rich upper atmosphere that was likely separated by a thin methane haze from the lower atmosphere. This methane layer would have prevented mixing between the two, which would explain the data supporting the oxygen poor lower atmosphere. Where the oxygen came from is still unclear; the current working theory is that the sun’s UV rays split CO2, but more research has yet to be done to figure out why.

In the meantime, Genge says the plan is to keep looking for micrometeorites to study and “potentially do a time sequence and see how the dust changed”. If lucky, they might find whether there were any changes in atmospheric oxygen content 2.7 billion years ago.

And while cosmic dust may seem far removed from our life, Genge argues sharing the fascination of research is key to sparking interest in science, which we should keep in mind in our studies and research: “What we’re doing is pushing the boundaries of science and coming up with these little gems about the past that excite people about science. I think if you talk to every single scientist, we all have an inherent interest in science, but there’s usually a book or a newspaper story or something, National Geographic or something, that made you go: Wow that’s really cool.”