Imperial puts forward a team in an international sensor building competition

The team aims to produce a fully functioning creatinine sensor which rivals those currently available

Imperial College has put forward a team of twelve students to compete in the International SensUs Competition, which aims to produce a creatinine molecular biosensor for healthcare applications. Its applications include uses in monitoring chronic kidney damage, radiology, the cardiovascular system and transplantation.

The other universities taking part in the competition include: The University of Leuven, Uppsala University, The Technical University of Denmark and Eindhoven University of Technology. SensUs is the first international student competition involving molecular biosensors for healthcare applications, and is being organised by students at the Eindhoven University of Technology in collaboration with professors from international universities.

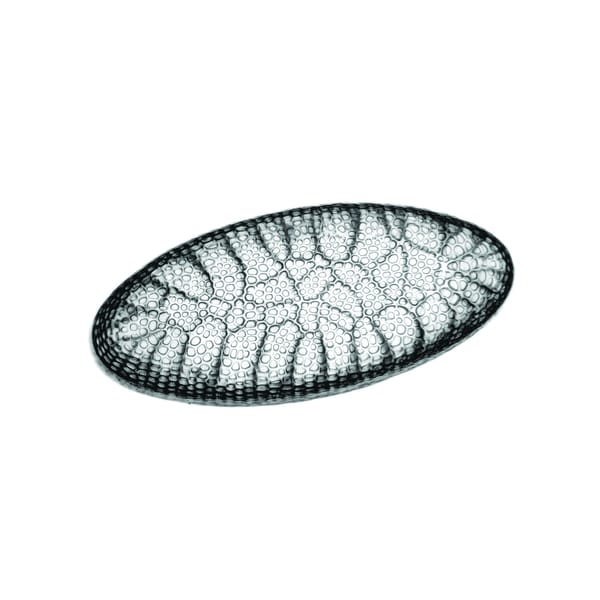

Creatinine is a by-product of the phosphorylation of creatine and is catalysed by the enzyme creatine kinase. Kinases are enzymes which use ATP (adenosine triphosphate, the body's immediate supply of chemical energy) to transfer phosphate groups onto molecules, such as creatine, turning ATP into ADP (adenosine diphosphate). The product of the reaction is phosphocreatine which is used to turn ADP back into ATP in times of high physical stress; phosphocreatine requires low effort to synthesize when the body has excess ATP.

Creatinine is useless to the body so it has to be removed by the kidneys. If the filtration in the kidneys is deficient, the level of creatinine in the blood rises. Consequently, by sensing the concentrations, doctors can determine kidney-associated illnesses in patients. It is therefore a very important compound and any improvements to current sensors will be a remarkable achievement. The sensing of creatinine has four main application areas: monitoring chronic kidney damage, the study of agents that are a burden on the kidneys in radiology, the study of the effects of diuretics on the kidney in cardiovascular studies, and in the monitoring of transplanted kidney function as part of patient care.

Professor Tony Cass and Doctor Christopher Johnson, the supervisors of the Imperial team, act as consultants to the Imperial team and are able to provide guidance to the team due to their extensive knowledge in both biochemistry, bioengineering and molecular biosensors. Although it is a student-only competition, the team seeks help on any specific problems encountered along the way and liase with the supervisors and various companies to attain any equipment or facilities needed. Moreover, they have generously contacted companies and are in charge of the teams funding. One company, OrionTM, has kindly supplied free electrodes to the team who are hoping to start working in labs in the summer term.

The Imperial College team aims to produce a fully functioning creatinine sensor which rivals those currently available. The Imperial team is made up of five chemists, John Welsh, Ana Losada, Ning Voon, Onur Guzel, and Taiwo Lawal, four bioengineers, Francesco Guagliardo, Edward Da Fonseca, Valeria Trujillo, and Riccardo Barbano, a biochemist, Rufus Mitchell-Heggs, mathematician, Lawrence Stewart, and a physicist, Thomas Lord.

The Imperial team is currently conducting market research on existing sensors by asking various experts in the field including clinicians, GPs and professors. They will use the information gathered to decide whether to improve on an existing model, which uses enzymes to detect the compounds in the blood, or to go in another direction, possibly researching the potential use of molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs). However, it is likely that they will split up into two teams so that they can experiment on both MIPs and enzyme-based sensors.

The team will be travelling to Eindhoven University of technology in the Netherlands on the 9th of September to present their sensor. Each sensor will be given 22 samples to be tested over three hours on Friday and on Saturday, the team will present their sensor to the public and a panel of experts, Professor Cass being one of them. Four independent awards will be given out by the end of Saturday: The Analytical Performance Award, based on the precision, range, speed and sample volume; The Creativity and Initiative Award, based on how original the sensor is; The Translation Potential Award, based on future applications in healthcare and how cost-effective it is; and The Public Presentation Award, based on the presentation skills of the teams.

While it would be an amazing achievement for the team to win an award, they are simply happy to have made a functioning sensor and contributed to the scientific field.

To follow the team's progress, like them on Facebook or visit their website: imperialcollege.sensus.org.