Documentary corner: Titicut Follies

Our regular film column

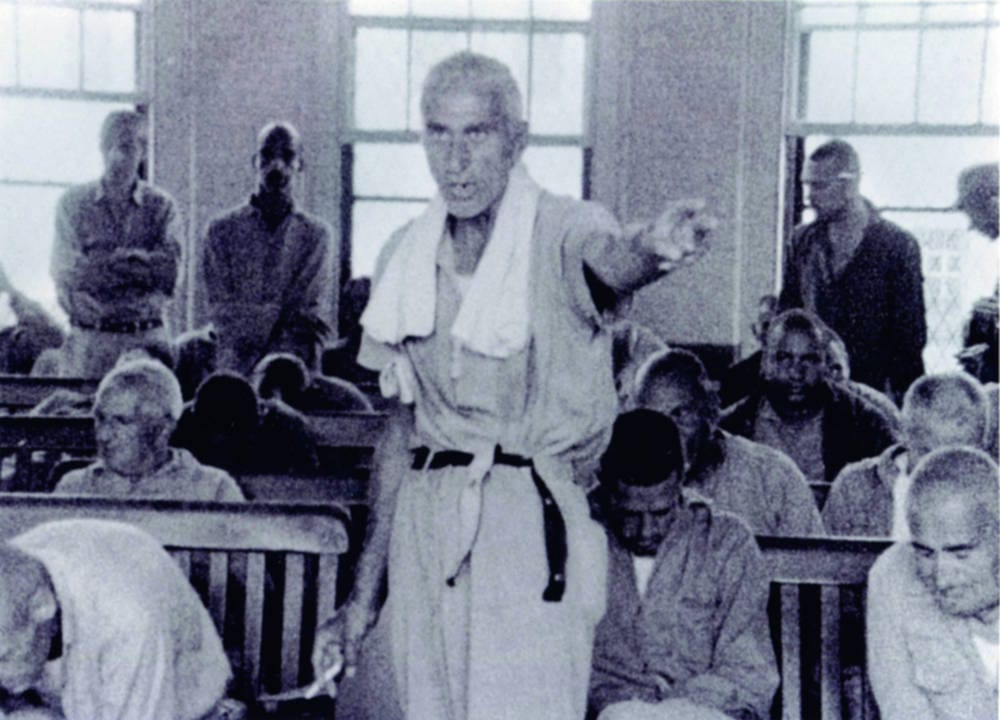

It seems fitting that Documentary Corner should end with a beginning. Titicut Follies is the first film from director Frederick Wiseman, a giant in the documentary world, who stormed into the Bridgewater State Hospital for the criminally insane in 1966, armed only with a camera and a whole lot of chutzpah. Over the course of 84 minutes, Wiseman exposes the goings on in the hospital, from the mundane to the horrific: we see prisoners being force-fed, stripped, and relentlessly taunted by the guards, who are on the whole indifferent to their charges’ well-being.

In one horrific scene, we follow a man back from a shave, who is mercilessly mocked by the guards, until he begins to scream at them in a rage; once back to his cell, he enters into some kind of trance, and paces around the room, stamping down his heels. Cameraman John Marshall, previously known for his ethnographic work, takes all this in impassively and relentlessly. The film takes its name from the in-hospital talent show, scenes from which bookend the film, and are the stuff of Lynchian nightmare. As the lines between inmate and guard blur, it becomes more and more difficult to distinguish between individuals, the whole scene spinning out of control like some kind of vision of hell.

What is astonishing about Titicut Follies is that it set a pattern for Wiseman that he has not yet deviated from. Over a career spanning five decades, he has stuck to his signature style: lengthy shots, no voice-over, no interviews, and no explanation. While his films may have gotten longer, he has doggedly remained faithful to these principles, resulting in over 40 arresting works, a large number of which focus on single institutions: 1995’s Ballet, which looked at the American Ballet Theatre; 1987’s Missile, which investigated the training courses for ICBM operators; and 1975’s Welfare, which took place in a single welfare office.

Through his work, Wiseman reveals himself as one of the world’s best editors. Eschewing any notion of objectivity in cinema, Wiseman admits that all film will be biased: ‘the editing,’ he says, ‘is highly manipulative’. Often ending up with at least a hundred hours of footage, he will go through it, picking out the best sections, and cutting it down to a taut narrative (that usually runs over several hours).

In Titicut Follies, Wiseman forces us to ask the question of what the ethical limits of documentary filmmaking are. He holds the camera still for as long as he possibly can, and then even further, breaking down the lines between observation and voyeurism. The ethics is complicated by the fact that he only received consent forms from the guards, and not from the prisoners, many of whom were not competent.

Just before its release in 1967, the government attempted to ban the film, and in 1968 they succeeded, making it the first film to be banned for reasons other than obscenity and national security. In 1987 inmates’ families sued the prison after a number of fatalities, and the prosecution team argued that releasing Titicut Follies in 1967 would have led to reform.

In many ways, Wiseman reminds me of Diane Arbus, whose photographs forced the viewer to look at something they would normally shy away from. ‘A lot of people,’ Arbus wrote, ‘they want to be paid that much attention. And that’s a reasonable kind of attention to be paid.’

Originally trained as a lawyer, Wiseman’s films stand up for their subjects, providing individuals with the means to represent themselves; in Titicut Follies he attempts to shine a light in one of society’s darkest corners, leaving us all enriched.