Czech elections throw the country into political turmoil

The rise of the populist ANO party means that the future of the Czech Republic is uncertain.

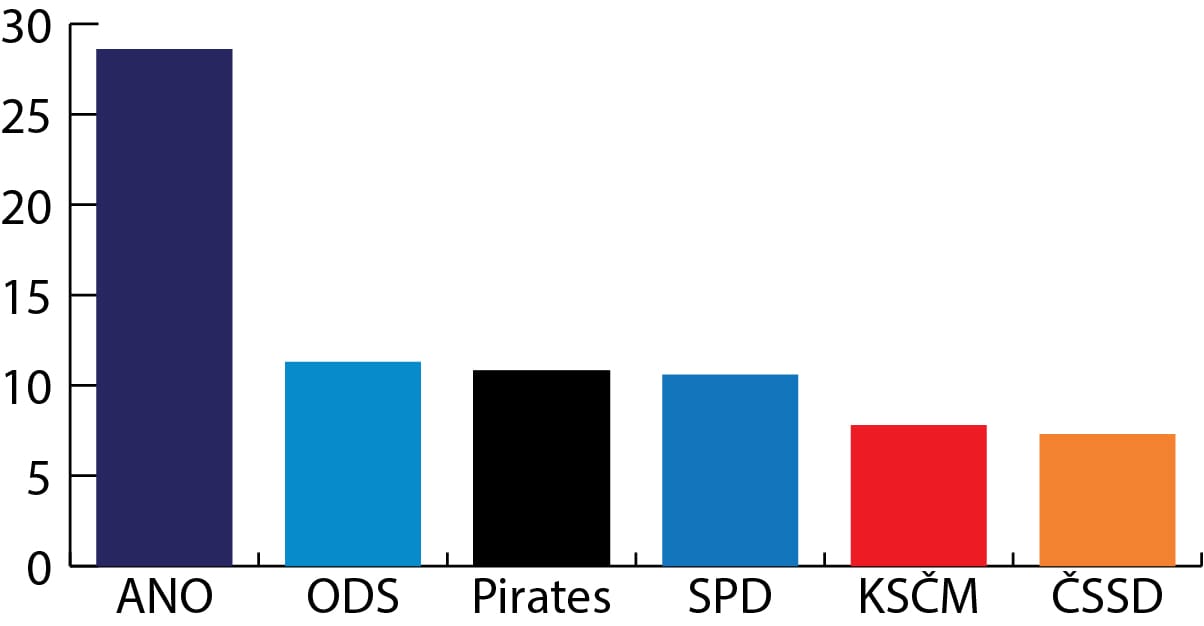

Last week’s legislative elections in the Czech Republic were record-breaking in many ways – most candidates and parties standing; most fragmented Chamber of Deputies to date, with nine parties crossing the 5% mark; and the first time in the country’s history that neither Civic Democrats (ODS) nor Social Democrats (ČSSD) won. These changes mark a shift in Czech voting tendencies, mirroring those found all across Europe.

The landslide victory of ANO, a centrist-populist party led by Czechia’s second richest man Andrej Babiš, was predicted by all polling agencies. However, prognoses about the remaining parties completely failed, grossly underestimating the appeal of the Pirate Party and the anti-immigration, anti-Islamic, Eurosceptic “Freedom and Direct Democracy” (SPD) which finished third and fourth respectively. They also failed to predict the poor results of the left-wing ČSSD and Communist party (KSČM) who each got a meager 7% – their poorest result yet. The reason for these inaccuracies? Although the authors of the polls claim we need to take standard error into account, the main factor was most likely the indecisiveness of many voters. This uncertainty reflects distrust and displeasure with the traditional parties, and so many of the wavering voters laid their hopes in the new, anti-establishment parties such as Pirates and SPD.

Although ANO established itself as the winner in all regions, a closer look reveals nuances: the party gained most of their new votes where ČSSD suffered the largest losses – thus it seems that ANO pulled its votes from Social Democrats, although the two parties have led the government together for the past four years. The country has prospered under their governance, maintaining a surplus budget for two consecutive years and decreasing the unemployment rate to the lowest in the EU. One can argue that both parties have a share in this success: however, ANO took the credit. Why is that the case? The persona of the ANO’s Andrej Babiš plays a major role, being cited as the second most influential factor in the election of the party.

But who is Babiš? The Slovak-born agricultural and media tycoon entered the political scene in 2011, when he founded his party, which he states was to express a dissatisfaction with the corrupted state. Although he describes himself as a self-made man, he largely benefited from his parents’ positions in the Communist party. However, much like Donald Trump and Silvio Berlusconi to whom he is likened, the voters don’t seem to mind his wealth. They also gladly turn a blind eye to many accusations against him – such as the ‘Stork Nest Case’ in which Babiš received EU subsidies intended for small enterprises for his recreation centre and farm, which is part of the large conglomerate Agrofert. He also allegedly cooperated with Communist secret police during the totalitarian regime. Babiš rejects all these accusations as political attempts to destroy him. Now that ANO is in power, what can we expect? Babiš is not a man of ideology, and that makes him unpredictable.

“The persona of the ANO’s Andrej Babiš played a major role in their success in the Czech election”

However, one can get an idea from his book where he outlines his vision of Czech Republic in 18 years: let’s dissolve municipal councils, regional assemblies, and the Senate, and streamline the system, he says; let’s run the state like a company. Such changes would concentrate power into the hands of a few, namely the MPs and the mayors, and raise concern about the preservation of democracy. The abolition of the Senate would also enable changes to the constitution without moderation. Another concept that Babiš would like to introduce is direct democracy – an idea appealing to the Pirates and SPD. Superficially, there is nothing as democratic as giving the power to the people. However, one must be wary of the consequences – after all, many voters tend to decide emotionally rather than rationally, and some decisions require expertise in the subject. As an example, direct democracy was one of the factors explaining why women in Switzerland were only granted suffrage in 1971. One of the first referendums would inevitably be about “Czexit”, as the anti-European mood is rising among Czechs. What would follow is unimaginable.

Where do the others come in? The gamut of political views in the lower chamber is colourful and reaching agreement will be difficult. None of the parties is willing to form a coalition with the ANO, with the exception of the SDP, but they are just as dismissive of a minority government. It’s only clear that there are many changes ahead: power within the parties is shifting as they deal with their defeats, and half of MPs have been replaced. The lower chamber has diversified as many politicians under 30s and women were elected, but has also become more polarized.

Czech Republic took a step in the populist, right-wing, anti-European direction, much like its neighbours Germany, Austria, and Poland. Where this road will lead is difficult to tell at the moment – hopefully not away from democracy.