In defence of ‘difficult’ books

Is a book ‘bad’ because it is ‘too difficult’ to read? Felix writer Ned Summers thinks the issue is in our approach.

There is no criticism more widely levelled against book and author than that of difficulty. I was prompted to write this article because of a one-star Goodreads review of Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49. It began:

“A classic English majors only book, aka people like talking about this book and that they ‘get it’ make you feel like their intellectual inferior.”

Readers and non-readers alike may describe books as dull; some refuse to approach ‘classics’ since they are dated whilst others, like our reviewer, will not touch modern literature because it is overcomplicated and self-congratulating. My hope is to show that often these are not bad books but they instead reveal fault in our way of reading them.

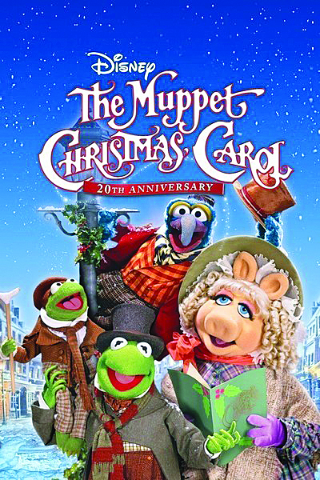

Each of these descriptions veil a common criticism: difficulty. To say a book is dull is to say that it is harder to absorb yourself in reading than in other media. Many old books are dated. Dickens’ vocabulary is unusual, his settings Victorian, and his ghosts are far from frightening but his stories resonate today as they did one hundred and ninety years ago – A Christmas Carol was even adapted into a movie by The Muppets! So datedness is not in itself a criticism but instead hides the fear that it is too difficult to distill Dickens’ stories from his language. Many modern classics are overcomplicated. Authors like Pynchon have written books that stretch the definitions of a novel but these are often books where difficulty is necessary in their aims.

There are bad books but in many cases the difficult book is not written poorly. The fault often lies with us in our approach to reading these books. For this I return to my angry Pynchon review which ends with:

‘If you enjoy art that makes a statement, try this book. If you enjoy books for the story they tell and the messages you can extract from that story, avoid this book. It’s up to you.’

Given the great diversity of authors and their books, the greatest determining factor for our enjoyment is how well our expectations match the book we end up reading. The books I’ve found most difficult have not been bad ones but ones that were not right, at that time, for me. These books either challenge our expectations of writing or challenge our expectations of the world.

No one can read Harry Potter and Oliver Twist in the same way. To expect to breeze through Dickens at the pace you would read Rowling is to set yourself up for disappointment. He is not so hard when you read him, as originally intended, in an environment without other distractions, such as to pass the time on Sunday afternoons. The reviewer above likes to read other things and writes that Pynchon is a bad writer for writing differently. He may indeed be a bad writer, but it would not be because of the difficulties this reviewer had.

Finally, there are books that weren’t written for you: books addressing issues you do not care about, have overlooked or struggles you do not understand. In One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez grants us insight into the Colombian culture rarely discussed in the UK. He opens a door for insight, but that requires empathy from a reader too. Books dealing with issues of oppression, like institutional racism, are often written for those within the community. Those of us outside the situation who attempt to read them should be aware that these works are not always written for us. These can be the most difficult books to read. A book is not bad for challenging your base beliefs, nor for asking you to empathize with characters different to yourself. When read considerately, these books can be far more enlightening and memorable than any ‘easy’ novel.

The relationship between book and reader is deeply personal and difficult to deconstruct. Our fault, as readers, is in expecting books to conform to what we want them to be before opening them, instead of allowing them to suggest different approaches. The perfect relationship is that of compromise, where you allow a book to change your perspective and grow from it. Sometimes, however, as with relationships between people, compromise is difficult. It is important to remember that often compatibility isn’t possible even when the other has few objective faults. Sometimes, the timing is just wrong.