Felix Politics takes on the Autumn Budget

Resident Politics Writer Abhijay Sood give his verdict on what it means for us.

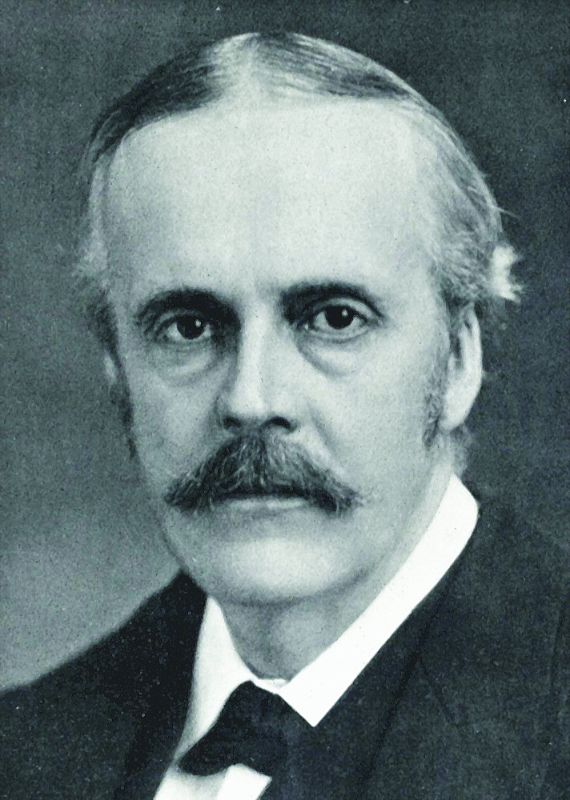

This Wednesday, the Autumn Budget was delivered by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Hammond. It entails details about government spending and borrowing, and related policies, in advance of the next financial year. This sort of thing sounds horrendously dull, but it’s important to appreciate the state of the country and what the government’s up to, and to treat those making decisions in our names with scepticism.

Some will welcome this budget, while others will feel it gives cause for concern. In either case, this budget is a symptom of the politically and economically precarious times in which we live: the government can neither follow through wholeheartedly on its past “austerity” policies, nor can they completely adopt the positions of their opponents, so they’re stuck in the middle, with Brexit further complicating things.

Housing

The Chancellor is taking three main steps to alleviate Britain’s “broken housing market.” These are:

- An investment package: £44 billion over five years for building homes

- A stamp duty tax cut: reducing the burden for first time buyers

- An increased levy on empty homes: allowing local councils to charge double the tax on unoccupied properties.

These steps are welcome, but fall short of addressing the issues that underpin the housing crisis in this country. According to members of his own party, such as the chairman of the Local Government Association, the investment plans do not adequately involve local authorities, suggesting it will be difficult to meet the requisite 300,000 homes built per year. The other issue with this investment is that, even under the government’s optimistic figures, this target is not reached until the middle of the next decade, meaning the housing stock will remain insufficient for years to come.

Regarding the council tax levy, though this may generate welcome funds for local authorities, it is unlikely to disincentivise those who own empty lots in major cities (where housing stock is most needed) from leaving them empty. The tax increase here represents a relatively small proportion of overall property tax, and pales in comparison to the property values. However, in the countryside, where properties are cheaper, this approach could help reduce the number of empty properties.

The stamp duty tax cut is interesting, since it is likely to affect those reading this article. We all welcome a saving of up to 5k on first time buying, but the IOBR suggests these changes will merely end up reflected in the cost of properties, mitigating the positive benefit. The huge deposits required to purchase property in places like London were not addressed.

The government is also making an extra £125m available for renters in areas where rents have sharply increased. This is welcome, but again fails to address the underlying reasons for these issues, which will continue to proliferate until more drastic action is taken.

Health & Social Security

Healthcare and social security are the two largest sectors of government spending. On the NHS, £10 billion has been pledged for frontline services over this parliament (next five years), while NHS England will receive £2.8 billion over three years. This is less than half the money requested by the director of NHS England to tackle ever increasing wait times and issues of understaffing (for context, total healthcare spending is ~ £145 billion). Discussions are currently taking place between the Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt and nurses unions on the issue of nurse pay, which has been stagnant since the Conservatives entered government in 2010.

“Social security was not discussed at length by the Chancellor, but he did mention the controversial “universal credit” programme”

Social security was not discussed at length by the Chancellor, though he did mention the controversial “universal credit” programme, wherein six means tested benefits are being rolled into one. This currently affects 600,000 people, but will soon reach millions more. Opposition parties and independent researchers have pointed out that many will lose out under this system (due to caps, floors, and tapers) and long wait times before receiving an initial payment could be extremely damaging to those living paycheck to paycheck – pushing people into poverty. Former Conservative Prime Minister John Major described the rollout as “unfair and unforgiving,” but the Chancellor has rejected calls to “pause and fix the program”. Maximum wait times have been reduced from six to five weeks, and though this may pacify moderate Conservative sceptics of the policy, it does nothing to address the other concerns raised by its implementation.

Education & Research

The budget did not discuss very granular education issues, though its announcements were still interesting and relevant to students at institutions like ours. It included a heavy focus on maths and computing, with additional staff to be brought in for both, schools encouraged to enrol more students on A-level maths courses, and an expansion of a “Singaporean-style” maths education at primary level. In addressing the numeracy gap between British citizens and those of other nations it is important that, alongside changes like these, efforts are made to change the culturearound mathematics and education generally (with more autonomy for teachers, for example).

Increases in investment for Research & Development are also likely to be welcomed by Imperial students, though the 2.4% spending target on R&D by 2027 makes it difficult to meet a 3% 2030 target. Tax credits have been increased (from 11% to 12%), and total spending should increase by £2.3 billion in 2021-22.

Tax & the Environment

The recent release of the Paradise Papers has added to pressure on the government on the issue of tax avoidance (which is legal, but widely interpreted as immoral). In response to this, the budget included provisions to tax profits being directed overseas at a higher rate than the corporation tax, primarily targeting digital companies such as Apple and Google. This is a welcome first step to addressing an endemic problem: £2.7 billion a year is lost to legal tax avoidance.

“Hammond made a number of overtures regarding the UK’s role in the environment”

The personal allowance, the value below which no tax is paid, is being increased. This lessens the burden on all taxpayers, although since other tax brackets are also moving, and due to complications with respect to the aforementioned universal credit program (where beyond a point, benefits are severely limited) high earners are the chief beneficiaries of these changes. The minimum wage is to be increased in line with recommendations from the low pay commission, but increases to the “National Living Wage” (which isn’t really a living wage) are slowing down.

Regarding the environment, Hammond made a number of overtures during his address to Parliament regarding our role on the international stage (drawing sharp contrast with the USA) and the importance of tackling issues including air pollution. On this front, a new levy is to be introduced on diesel cars that fail to meet a certain criterion, with this and other measures encouraging the uptake of electric vehicles. Nevertheless, almost all other policies discussed pertaining to this area in the budget do not assist with environmental problems, and many do the opposite. Overall fuel duties have been frozen, and North Sea oil producers are being given a tax break. Even the diesel levy conspicuously exempts “white van men,” highlighting the politically precarious position the government is in (not wanting to be perceived as ‘punishing swing voters’), and limiting the positive impact these changes will have in terms of both carbon emissions and air quality.

It’s the economy, stupid

There is no sugar-coating this: the economic outlook is not good. Growth forecasts – from the non-partisan “Independent Office for Budget Responsibility” (IOBR) – have been revised down. Since the recession, productivity growth has been sluggish, and accounting for this the IOBR have forecasted slower economic growth than previously anticipated, leaving us on course for the longest fall in living standards since records began. Employment reaching a near historic high is fantastic news (though unemployment isn’t zero, as the Chancellor accidentally intimated earlier this week), but low productivity growth and real terms pay decreases limit the positive impact this may have.

The government is also still borrowing more than it is spending, to the tune of around £40 billion. While this isn’t a problem in itself, it puts the government in a difficult place politically. They have repeatedly attacked Labour for running deficits in the past, but have been unable to meet their own targets for deficit elimination since taking office, moving the goalposts from 2015, to 2017, to 2020 and now to the “mid 2020s”. The emperor has no clothes, and even this last target seems unlikely to be met in light of Brexit, according to the credit agency, Moody’s.

The rhetoric the Conservatives have adopted since 2010 on the deficit is notable. While Hammond has softened up a little, making some sensible noises regarding investments and incentives, even he repeatedly put forward in his Wednesday address the notion that the economic malaise of the late 2000s was “Labour’s Great Recession”: that mishandled public finances, rather than a global financial crisis, led us to the position we’re in today. You only have to look at the rest of the world to understand why this is not the case. The Chancellor may just be playing politics, but ‘deficit hawk’ rhetoric will not forever play well for the government. It either hamstrings their ability to pursue sensible fiscal policy for political reasons, or will result in an internal or electoral backlash once it becomes clear they’re “just as bad as the other lot” on borrowing. The government’s hand might be strengthened going forward, particularly with Brexit on the horizon, if they are a little more forthcoming in this area.

Conclusion

Given current affairs and the political position of the government, this budget has been reasonably well crafted by the Chancellor. It does not resemble Osborne’s past austerity measures nor the feared ‘punishment budget’. However, it is indicative of a government with little room and few ideas: addressing issues around the edges without the necessary political capital to affect root causes. The issues not mentioned in this budget, from tuition fees and social care on the one hand to school meals and the ‘dementia tax’ on the other¸ say just as much as those that were about the position this government finds itself in. With economic uncertainty, worsening forecasts and political triangulation on the part of both external and internal opponents, Hammond will have little room to manoeuvre as the country steers itself out of the European Union.