One nation, under a meme: how 2017 was the year that memes brought us together

While last year Pepe the Frog was propelling orange demagogues into the White House, this year we’ve seen memes act as a form of resistance against Trump, explore their own meanings, and bring us together in real life to celebrate Big Shaq.

If one wants to explore what memes have become in modern society, one only needs to explore the sad case of Pepe the Frog. A meme that started out in 2005 as a form of internet humour, mainly used across the netherworld of 4chan, by last year, the image had been appropriated by a number of alt-right groups. Today, the Anti-Defamation League, an international organisation that have historically opposed the KKK and the German-American Bund of the 1930s, lists Pepe as a general symbol of hate.

Pepe, and its associated alt-right movement, also did the unthinkable, and helped propel a Wotsit-orange political dilettante, who had openly bragged about being a sexual predator, into the White House. It is impossible to say whether memes were what determined last year’s presidential election, but it is certain that memes and meme culture will forever be inextricably linked to the strange turn of events of the months leading up to November 2016.

Memes as Resistance

If 2016 was the year memes determined political outcomes, 2017 shows us what happens when nihilistic internet humour comes up against the harsh reality of political power. Trump’s presidency has thus far been a veritable goldmine for meme creators – a sentence nobody could have predicted being written. Everything about his presidency has memetic potential: from #FreeMelania, which spread after a video of Melania Trump looking less-than-thrilled at the inauguration emerged, and competed for space with other inauguration memes, such as Michelle Obama doing a Jim Carrey-style side-look to the camera after being handed a gift from the new First Lady; through to his elaborate water break last month during a speech about his visit to Asia.

In some ways, the creation of memes can be seen as a form of resistance against Trump, an attempt to take him down a peg, and remind everyone that he really is just an enormous joke. If memes allowed the demagogic man-child into the Presidency, they seem to say, memes are what will allow us to live under his rule. In a TIME magazine article from May, for example, it was revealed that when Trump served dessert to his guests, “he gets two scoops of vanilla ice cream with his chocolate cream pie, instead of the single scoop for everyone else”. Such meme fodder was quickly picked up by the online community, who used it to imply that Trump has a similar mentality to a five-year-old child.

“Everything about Trump’s presidency has memetic potential for online communities”

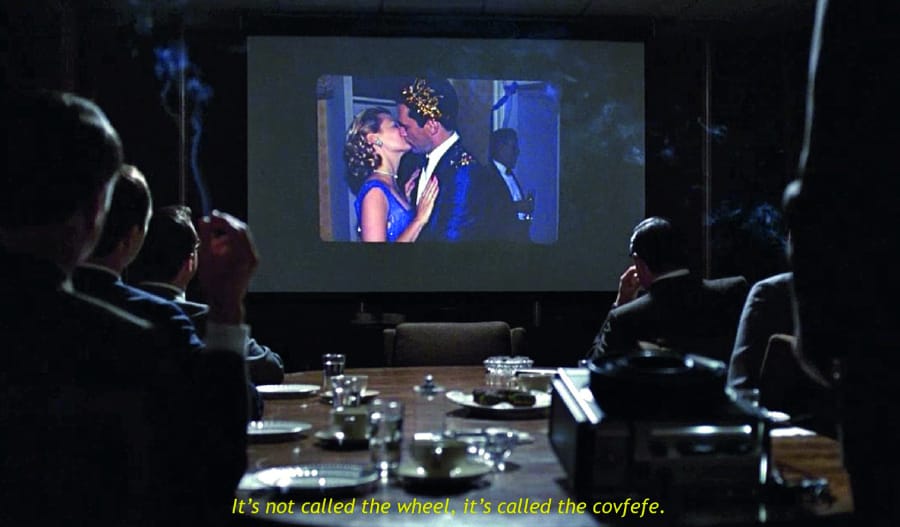

This function, of memes-as-resistance, can perhaps best be seen in the short boom and bust meme cycle of ‘Covfefe’: just after midnight at the end of May, Trump tweeted “despite the constant negative press covfefe” without any explanation, leading some to presume that he’d either had a stroke or had his phone knocked out of his hand by an aide who has had enough of his online diatribes. The tweet stayed up for around six hours, by which time it had set the internet alight, with numerous parodies inserting the word into scenes from film and TV shows. At 6:07am, however, Trump followed it up with “Who can figure out the true meaning of “covfefe” ??? Enjoy!” And just like that, after having gained acknowledgement from the very person it was supposed to be making fun of, the meme was dead. For Trump memes to function, it seems to suggest, the subject cannot engage with them.

These are only a few examples of what a gift Trump’s presidency has been for meme makers. But what does this desire to create humour from his actions mean? Some of the memes that have been created were done so following behaviour that would be – in any normal democracy – completely abhorrent. We’ve had Trump tossing paper towels to victims of hurricane victims in Puerto Rico – a territory still reeling from the disaster while Congress discuss tax cuts for the rich – and Kellyanne Conway discuss “alternative facts” with grave seriousness, whilst propagating lies about fictional terrorist attacks. You’ve got to meme, otherwise you’ll cry.

The Rise of Meta Memes

Over the past few years, memes have become increasingly complex and self-referential, with some memes packing in several layers of meaning into a single image – like a modern update of Elizabethan portraiture. In 2017, this was perhaps best exemplified by the Distracted Boyfriend meme. Based off a stock image showing a man turning to appreciate a woman in a red dress, while his appalled girlfriend looks on, the meme quickly took off, with content creators attributing various characters and themes to the three ‘characters’ (my personal favourite came from Penguin Random House, with the guy eschewing “knowing when to use a semicolon” for “em dash” – far too relatable).

What set this meme apart, however, was the way users enabled the meme to keep on delivering: today, in our constantly-online world, the lifespan of a meme has considerably diminished, to the point where 24 hours can be enough for one to run its course. What made the Distracted Boyfriend meme different, however, was users discovering different stock images from the same shoot, combining memes together, and using the meme itself to poke fun at the intrinsically transient nature of the form.

As time went on, the layers of the meme kept on building up, as users created loops of regression, flipped image formats, and created their own narratives. Really, the Distracted Boyfriend meme showed what memes can do best: bring people together, to create their own stories, if only for a short time.

Bringing us Together

This use of memes to bring people together can also be seen in the rise in event-based memes that we’ve had over the last year. Numerous meme-makers have been using Facebook events to propagate particular memes, such as the song ‘Africa’ by Toto, or simply to get people to say they’re going to events that have no purpose in the real world. This October, for example, Stephanie Reid created an event called “Windex the Bean”, inviting Chicago natives to clean Anish Kapoor’s famous sculpture Cloud Gate. The event description read “The Bean is dirty”. Such events can often spread like wildfire along social media networks, achieving hundreds if not thousands of attendees.

It’s a phenomenon some Imperial students have experience of: just a couple of weeks ago, the Imperial meme page Memeperial created an event for “Prince Harry’s Stag Do”, in collaboration with a number of other meme pages on Facebook. At the time of writing, the event has nearly 40,000 attendees, with more than 100,000 interested in attending. It reached such prominence, that BBC News reported on it, which they took time to point out was “not in any way official”.

Paul Balaji, Imperial’s most meme-able student, was the one running the event page – why did he do it? Speaking to Felix, he tells us “in the modern day of social media, a royal wedding isn’t just a national celebration, but rather a global phenomenon. Creating the event felt like the right thing to do – it was literally just a bit of banter at first. The more it grew, the more I realised it would have a life of its own, so I updated the description to reflect that it would be an international celebration of love.”

The Ting Goes...

Do memes really have the power to bring us all together? One of the most successful memes this year might prove that this is the case: at the end of August, Michael Dapaah’s fictional rapper Big Shaq entered Fire in the Booth, a regular show by BBC Radio 1Xtra DJ Charlie Sloth. The result was a 22-minute long video that generated countless memes, from “man’s not hot”, through to “2+2 is 4, minus 1 that’s 3, quick maths” and the iconic “the ting goes skrrrahh”.

What makes this meme particularly interesting, however, was the way it broke the geographical boundaries implicit in its creation: Big Shaq is an example of a piece of comedy that is extremely local, making cultural references rather specific to South London. From roadmen refusing to take off their jackets, to extremely poor freestyling, everything about his Fire in the Booth is steeped in London culture, which makes it popularity all the more beguiling.

“When your friends in New York laugh at ‘The Ting Goes’, are they laughing at the same thing?”

While the memes are certainly more popular in the UK, they have also spread across the world, popping up in the United States as well. And as much as you would hope internet dwellers in California are able to understand the humour being used by Dapaah, it’s only too common to come across people who don’t understand that the whole thing is a joke: “haha, he’s so bad at rapping”, you read in the YouTube comments, as you bury your face in your hands.

Big Shaq can, in some ways, highlight both the potential reach of a meme, and its potential limitations. While Stormzy’s Gang Signs and Prayer hit the top spot in the UK earlier this year – and well-deservedly – it failed to make much of an impact in America, showing that even in a culture slowly becoming more homogeneous, there will be local variants forming a cultural context in which memes are incredibly embedded. Your friends in New York might be laughing along with you as you show them a ‘The Ting Goes’ video that cuts to footage of Big Ben, but are they coming from the same point of view? Are they laughing the same laugh?

It seems that while memes are gradually being thrust more and more into the spotlight, they throw up more questions than answers. I look forward to the time in the near future when a new generation of cultural theorists will embrace this new method of communication, exploring the meaning behind the meme – who will be the Margaret Mead of the meme generation? Maybe you and me.