Denial

You're in the Denial? Join the club.

In a political climate increasingly described with the neologism ‘post-factual’, director Mick Jackson’s latest film Denial is sharply relevant. Centering around the libel case of British Holocaust-denier David Irving against American historian Deborah Lipstadt – a case that was often referred to as ‘history on trial’ – Denial make a convincing case for the importance of historical truth, and the dangers of wilfully misinterpreting facts.

The film opens several years before the trial, with Irving (Timothy Spall) upsetting a Q&A held by Lipstadt (Rachel Weisz) in promotion of her book Denying the Holocaust. In the book, Lipstadt accused Irving of deliberately distorting historical evidence to claim that Hitler did not murder millions of Jews and, subsequently, that the Holocaust was a lie. This initial scene sets up the templates the characters will follow: Irving is irascible and attention-seeking, goading his opponents to fall prey to his rhetorical traps, and glorifying in the subsequent uproar; Lipstadt is full of burning anger at those who try to belie the human costs of the Holocaust, but her fiery temperament means she comes off worse-for-wear in the initial confrontation.

We then skip forward a couple of years, and Irving is serving libel papers against Lipstadt for her claims. He makes the tactical decision to make the claim in the UK, where the burden of proof is on the defendant, forcing Lipstadt to travel to London and try and argue against Irving’s claims. She is assisted by top-flying solicitor Anthony Julius (Andrew Scott) and represented by barrister Richard Rampton (Tom Wilkinson), who decide that the best course of action is for Lipstadt to stay quiet, depriving Irving of the oxygen of publicity.

The result, is a script from playwright David Hare that relies too heavily on a one-note culture clash between American and British cultures. Weisz’s Lipstadt is the typical American: all action, she gets frustrated with her more subdued colleagues; The Brits, in contrast, are all softly-spoken, slightly slippery and oily (seemingly Andrew Scott’s favoured role), with a penchant for tradition and claret. As with his theatre work, Hare’s scriptwriting has a terminal lack of nuance, which at points spills into crass emotional exploitation (Auschwitz is a site which deserves more solemnity than a saccharine Howard Shore score can offer).

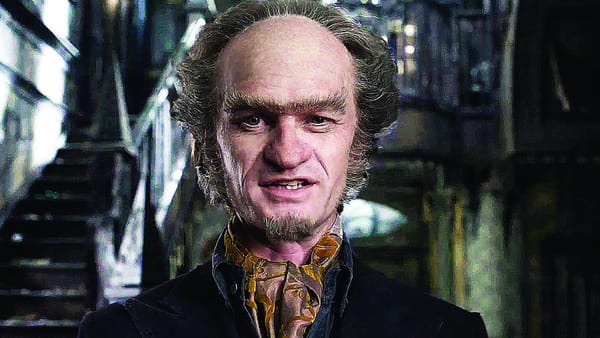

That being said, Denial remains undeniably entertaining, and manages to successfully explore the intricacies of the British legal system – which, as Lipstadt mentions, is somewhere between Dickensian and Kafkaesque – without being bogged down in the minutiae of complex details. Weisz gives Lipstadt a fierce dignity, making her an extremely likeable heroine, while Spall absolutely excels as Irving: he falls naturally into the role of gross villain, coming across like a serpent feasting on a particularly plump rat. Despite its tendency to err on the side of simplicity, Denial remains a solid courtroom drama, one that surveys our labyrinthine legal structure whilst remaining highly engaging.