Pluto: a manga come to life

A production that is a feast for the eyes explores artificial intelligence and what it means to be human

Pluto, in summary, is the most visually impressive play you’ve likely never heard of. Before seeing the show, all I knew was that it involved Astro Boy, a character I vaguely recalled from my childhood. What I now know is that my interest in the ethical questions underpinning artificial intelligence has grown tenfold.

In essence, Pluto is a sci-fi mystery: the world’s most powerful robots are being murdered, and a detective, who happens to be a robot himself, is attempting to solve the case. The production, which is the culmination of seventy years of sci-fi history, explores the question of what it is to be human.

In 1951, Osamu Tezuka, a cartoonist working hard on creating light-hearted yet meaningful comic strips in post-war Japan, created the character of Captain Atom (later to become just Atom, aka Astro Boy): a child-like robot working for peace. In 2003, Naoki Urusawa and Takashi Nagasaki worked together to write a new manga, in honour of Atom’s fictional birth date, April the 7th 2003.

The story created was Pluto, which is now passed on into the hands of director-choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui. Cherkaoui’s background in dance and theatre blend together in Pluto – it is clearly the work of a mind skilled at using movement to represent thought, emotion, and time. One of the more striking uses of dance – and there are several to choose from – is the depiction of a robot’s inner process by the actions of four or five dancers around it. When the detective, Gesicht, acts out his usual morning routine, dancers surrounding him convey his every thought with little gestures which, upon first glance, appear busy and overwhelming. Upon further glances, it becomes clear that the impeccably timed hand movements signal each of Gesicht’s thought processes as they happen.

Many of the movements of the performers throughout the show were blink-and-you’ve-missed-it, but the one that affected me the most was a simple movement of Gesicht sitting on a chair and being pushed (by the dancers) through a white frame. The simple enough movement was to signify his leaving the dressing room and entering the dining room where his wife awaited him. I only caught the end of the swift and elegant movement, and was left with a strong desire to press rewind to see the action again. I had the opportunity later in the show when the same action was repeated but, as I was reading surtitles at the time, missed it once again.

Which brings us on to the defining feature of the show: surtitles. Used at times synonymously with subtitles, surtitles have a similar meaning: the translation of the script is projected for the audience’s benefit, but do not include the usual descriptions of sounds that would be provided for deaf and hard of hearing audiences.

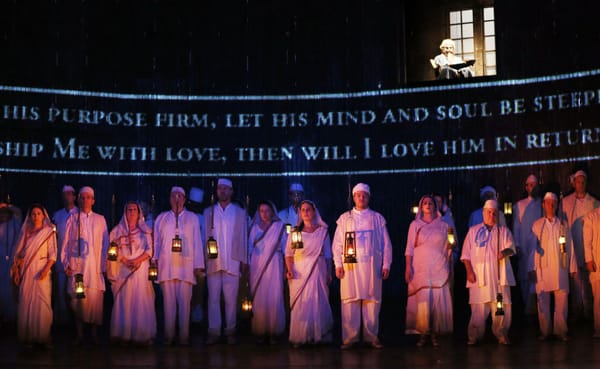

Pluto was performed completely in Japanese by the Bunkamura Theatre Cocoon, a theatre company based in Japan, which meant that the surtitles were necessary, and indeed did become a part of the show. Rather than restricting the surtitles to above or below the action, the surtitles were projected within the show itself, adding to the overall effect of an integrated manga comic. The two-tiered stage design constantly changed shape with the aid of background dancers who continuously moved white blocks and borders. The surtitles were projected within the black spaces created and on the white borders and blocks, sometimes alongside manga illustrations. The impression intended on the audience was that of reading a gigantic comic book. And it worked.

The downside to surtitles, as frequently is the case with subtitles, is the opportunity for mistakes. Occasionally, the words were displayed too early or too quickly for the audience to read but, given how infrequent the mistakes were and how many were possible – the location of the projections changed with every other sentence – the mistakes were not bad enough to be irritating. The only other problem of having to read a translation was a general weakness of the play altogether: the sheer amount of action to watch was, at times, a little too much. Yet, it is impossible not to be in awe of how Cherkaoui coordinated the timing of everything. Robot puppeteers, dancers, and minor characters all worked seamlessly throughout the show and it was startling to realise at the end that it was a cast of fifteen, not fifty. Tao Tsuchiya should be especially praised for her performance as both of the lead female roles, something I hadn’t realised until I noticed one of her characters missing from the curtain call.

Tsuchiya and the rest of the Pluto cast were spectacular, and deserved far more than a mere four days in London. With any luck, they’ll return to our shores again soon.

Pluto

4.5 Stars

Where? Barbican When? 8th - 11th Feb