The Devil’s Dance – dancing on the border between imagination and reality

Uzbek exile novelist Hamid Ismailov’s novel draws from rich Central Asian culture and poetic tradition, in an exploration of what it means to be a writer.

The death of Islam Karimov, the dictatorial leader of Uzbekistan, nearly two years ago, dropped the country into a quagmire of uncertainty. The leader, who had held power for 27 years, was widely criticised for his use of torture, crackdown on press freedoms, and a 2005 massacre in which around 400 protesters were killed. In a turn of events that seems right out of a postmodern satire, the news of his ill-health was announced on his daughter’s Instagram account.

Out of this chaos and turmoil, the Uzbek novelist Hamid Ismailov, who was forced to flee Uzbekistan in 1992 for Britain, had his first Uzbek-language novel published in the Central Asian nation in 25. Literature, like life, finds a way.

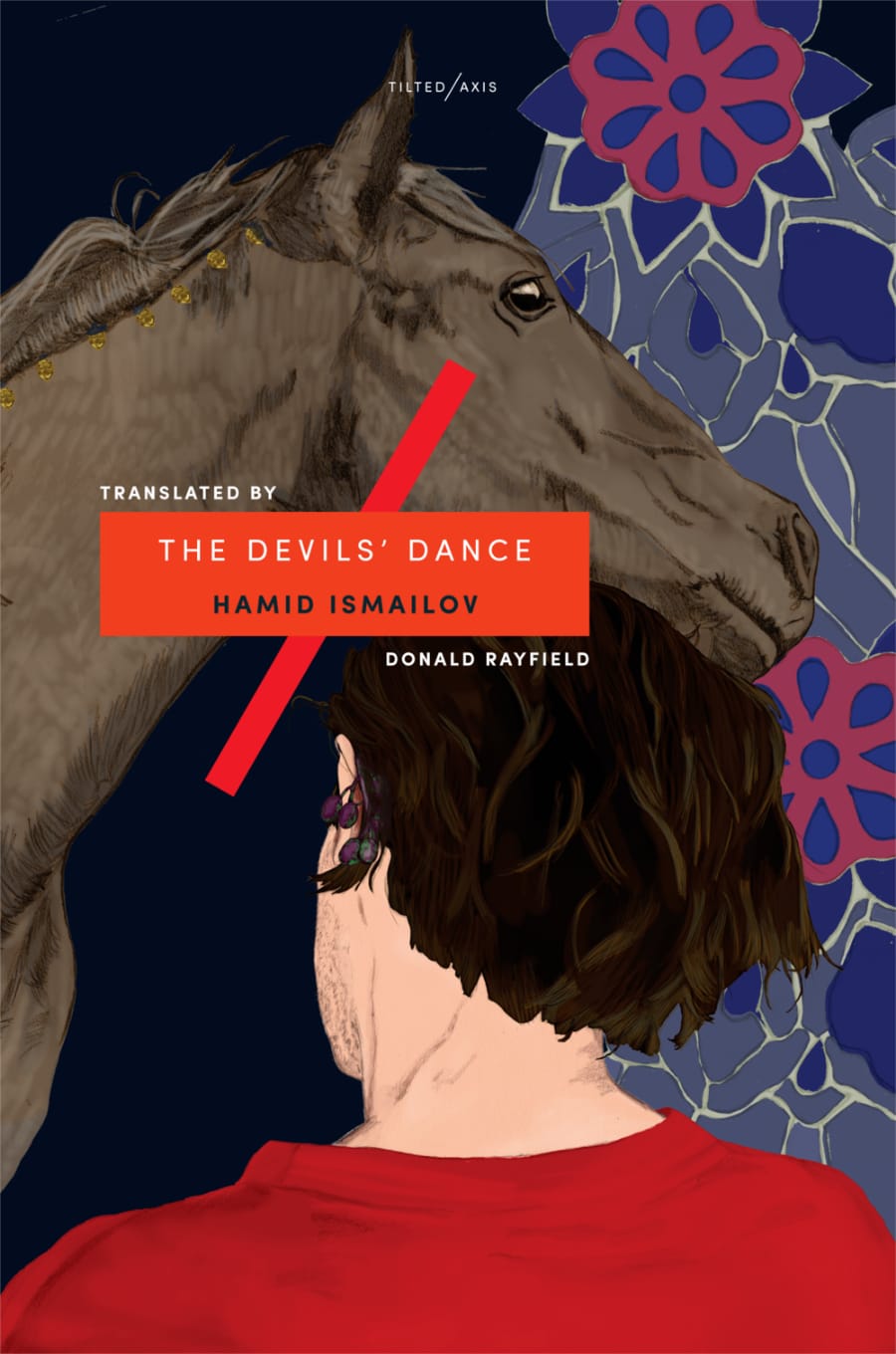

The novel that was published, The Devil’s Dance, now finds its way into English-readers hands, thanks to a translation from Donald Rayfield, printed by publishers Tilted Axis. Rayfield, working closely with Ismailov and fellow translator John Farndon, has produced a moving translation that flows beautifully, while retaining a number of stylistic and structural elements that could make the translation difficult.

The Devil’s Dance reads something like a cross between classical Central Asian poetry and a postmodern deconstruction of the function of the novel. The story primarily centres around the life of Abdulla Qodiriy, perhaps the most popular Uzbek novelist of the 20th century, although little-known in the West. Opening with Qodiriy tending to his garden, suffused with the idea for a novel that “would be a terrific story, surpassing both Past Days and The Scorpion from the Altar”, he is quickly arrested by the Soviet secret police, as part of Stalin’s Great Purge. Ismailov immediately plunges us into a world of political prisoners and jail cells, intrigue and horror.

Within this framework, Ismailov takes us inside the mind of Qodiriy as he struggles to conceive of the uncompleted novel – Emir Umar’s Slave Girl – and try and finish it within the cold walls of his cell. This secondary novel, set during the ‘Great Game’ of the 19th century, in which English and Russian spies wormed their way into the royal courts of Central Asia, centres around Oyxon – a poet and queen, passed from ruler to ruler, trapped within the confines of palaces. It’s a more palatial setting that Qodiriy’s, but it’s still a prison.

“It is a novel that celebrates the rich history of Central Asian culture – one political repression threatened to erase”

Ismailov plunges us deep into a world of double-crossing, poetry-spouting royalty, introducing a retinue of historical figures, such as Nasrullah, the ruler of Bukhara, Emir Umar, the leader of Kokland, and Nodira, his beautiful wife, and one of the most acclaimed Uzbek poets of the age. Qodiriy develops a deep identification with Oyxon, whose predicament resembles his own: “only when he know Oyxon’s life from beginning to end would he be able to bring his own life to its conclusion”, Ismailov writes. Qodiriy implores God to allow him out “safe and sound; then he would finish his tale of Oyxon and follow it up with a new, more hard-nosed novel, set in modern times.” He never makes it out, instead being executed in the October following his arrest. The novel he is constructing in his head during his prison sentence is lost, and it is up to Ismailov to reconstruct it for us.

The novel, with its foundations deeply set in Central Asian literature and poetry, mines both One Thousand and One Nights, and the lyrical poetry of the 19th century as inspiration. And yet unlike Scheherazade, who needs to keep on telling stories to secure her safety, Qodiriy is acutely aware of the limitation time has on his imagination: “A Thousand and One Nights goes on and on only in fairy tales”, his jailers tell him, “We can put a stop to this right now.”

It is this undercurrent of ever-present danger that drives him in a quest for survival, as he attempts to hold on until he can complete the novel. In Ismailov’s exploration of the nature of literature, he highlights the difference between the conception and completion of a novel, as well as the reasons behind the drive to create art. The novel is “an enquiry into a human being’s spirit, his identity, in much the same way as a prison interrogration,” a jailer informs Qodiriy, highlighting the power and violence of writing.

For Ismailov’s Qodiriy, as well as Qodiriy’s Nodira and Oyxon, writing has an intoxicating power over their own lives, and the lives of others. Qodiriy is “aware of the effect that the ‘made-up’ could have on real life”, and the threat that his writing will “vanish without a trace” hangs over him. As one aphorism quoted in the book goes: “Saying ‘halva’ once doesn’t bring a sweet taste to your mouth, but after a hundred times, your teeth will start sticking together”.

Interspersed with poetry translations from Farndon, The Devil’s Dance is a novel that celebrates the rich history of Central Asian culture – a culture that political repression threatened to erase. From descriptions of Uzbek nature and food – the rice dish plov is frequently mentioned – to celebration of the Uzbek language, Ismailov’s novel is a vital introduction to a world I’d never encountered before. While it can be a bit heavy going for readers like me, with no exposure to Central Asian culture, and many of the historical references flew straight over my head, it remains a beautiful and nuanced exploration of what it means to be a writer.