Bombs dropped during WWII had effects even at the “edge of space”

World War II is widely known to be the most devastating and deadly war in the history of mankind. However, the study of its impacts beyond Earth is very recent and could play a major role in improving modern technologies. In a study published last month, professor of astrophysics Chris Scott and historian Patrick Major from the University of Reading reveal that the shockwaves produced by Allied bombs dropped on European cities during WWII reached the edge of space, and temporarily weakened the ionosphere.

The ionosphere is a thick band in the outer atmosphere situated between 80km and 580km above the surface of Earth. It is formed due to atmospheric absorption of X-rays and ultraviolet light from the sun, and is very sensitive to solar activity such as the emission of particles carrying energy, high-speed solar winds and coronal mass ejection. These events can cause variances in the concentration of ions and electrons in the ionosphere, and thus cause it to become electrified. The study shows that the bombing raids were powerful enough to periodically decrease the concentration of electrons in the ionosphere, which could have interfered with the radio communications at low frequencies during the conflict.

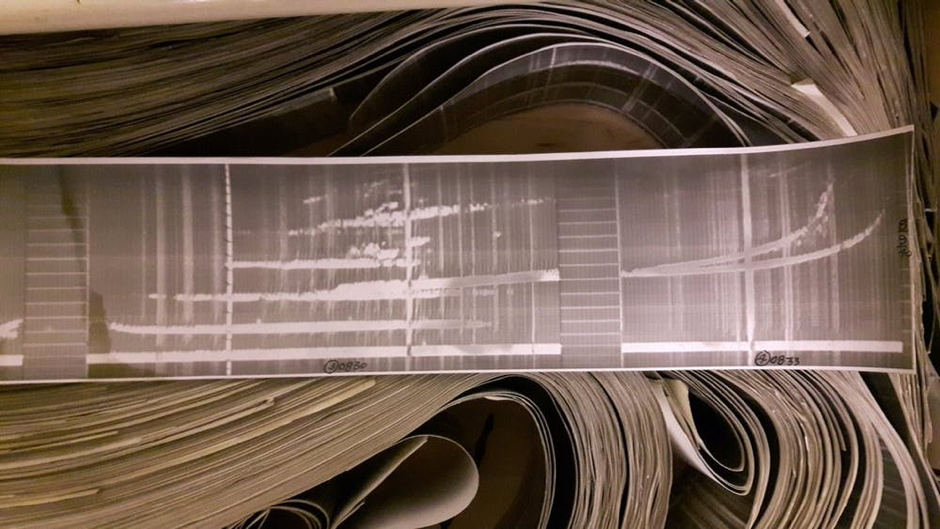

The researchers compared daily measurements of the ionosphere collected between 1943 and 1945 by the Radio Research Centre in the UK city of Slough, to the time and dates of 152 important Allied bombing raids over France and Germany during the same period. They found that changes in the ionosphere were occurring after these raids, which were meticulously recorded by the German authorities and in the Royal Air Force mission logbooks. Its “critical frequency,” or in other words the frequency of the radio waves reflected by the ionosphere’s constituent particles, decreased – which lead to a drop in the concentration of electrons. To describe the process mechanistically, energy released by the shockwaves heated the ionosphere, which then enabled the electrons to gain enough kinetic energy to escape from the ionosphere.

Although temporary reductions in the concentration of electrons is usually due to the sun, or are caused by natural phenomena on Earth such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and lightning, “it is astonishing to see how the ripples caused by man-made explosions can affect also the edge of space,” say the authors. The paper reminds us that over the course of the war, the Allied air forces dropped more than 2.75 million tons of TNT – the equivalent of 185 Hiroshima H-bombs – and that “each raid released the energy of at least 300 lightning strikes.”

One may wonder why the study didn’t focus on German bombing raids which occurred closer to Slough, where the measurements were taken, such as the well-known “London Blitz” which took place between September 1940 and May 1941. As C. Scott explains, “this bombing was more or less continuous, making it difficult to separate the impact of wartime raids from those of natural seasonal variability.” Furthermore, the Allied four-engine planes could carry bombs four times heavier than the two-engine German planes, which caused greater disruption and produced a clearer signal. This research may also have a significant impact on solving present-day scientific problems. Understanding the effect of manmade atmospheric disturbances could improve communications and global positioning systems (GPS) technology, which rely on the ionosphere. For example, airplanes had to come back to their base in October 2003 due to GPS inaccuracies, which were caused by disruptions in the ionosphere after an intense storm on the sun. More accurate knowledge of the ionosphere and the effects of disturbances could thus help develop prediction models useful for our modern technologies.

While the effects of the bombing raids on the ionosphere resulted in no long-term consequences for the atmosphere, the destruction they caused on the surface of Earth remain indelible marks in the world’s landscapes, towns, and also in the memory of survivors. The historian involved with the study, Patrick Major, reminds us of some of their experiences, such as “aircrew involved in the raids reporting having their aircraft damaged by the bomb shockwaves, despite being above the recommended height” or “residents under the bombs routinely recalling being thrown through the air by the pressure waves of air mines exploding, and window casements and doors would be blown off their hinges.”

Studying the past to understand the present is one message to take from this pioneering work. We should never forget “the images of neighbourhoods across Europe reduced to rubble due to wartime air raids, lasting reminder of the destruction that can be caused by man-made explosions”.