Left Off the Shelf

Despite increasing diversity in many industries, the literary scene is still white-dominated. Books writer Rahul Mehta explores the reasons why and what we can do about it.

Despite the power of prose and verse to drag us from our seat on the Tube (or grim university flat) to the Victorian slums or outer sectors of the Galactic Empire, British literature is still being held back. While the characters in books transcend time and space, the non-fictional people who write and publish the books suffer far greater restrictions in terms of diversity.

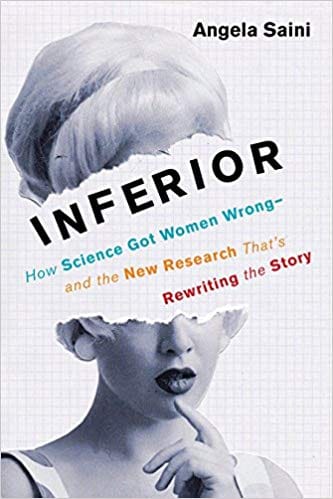

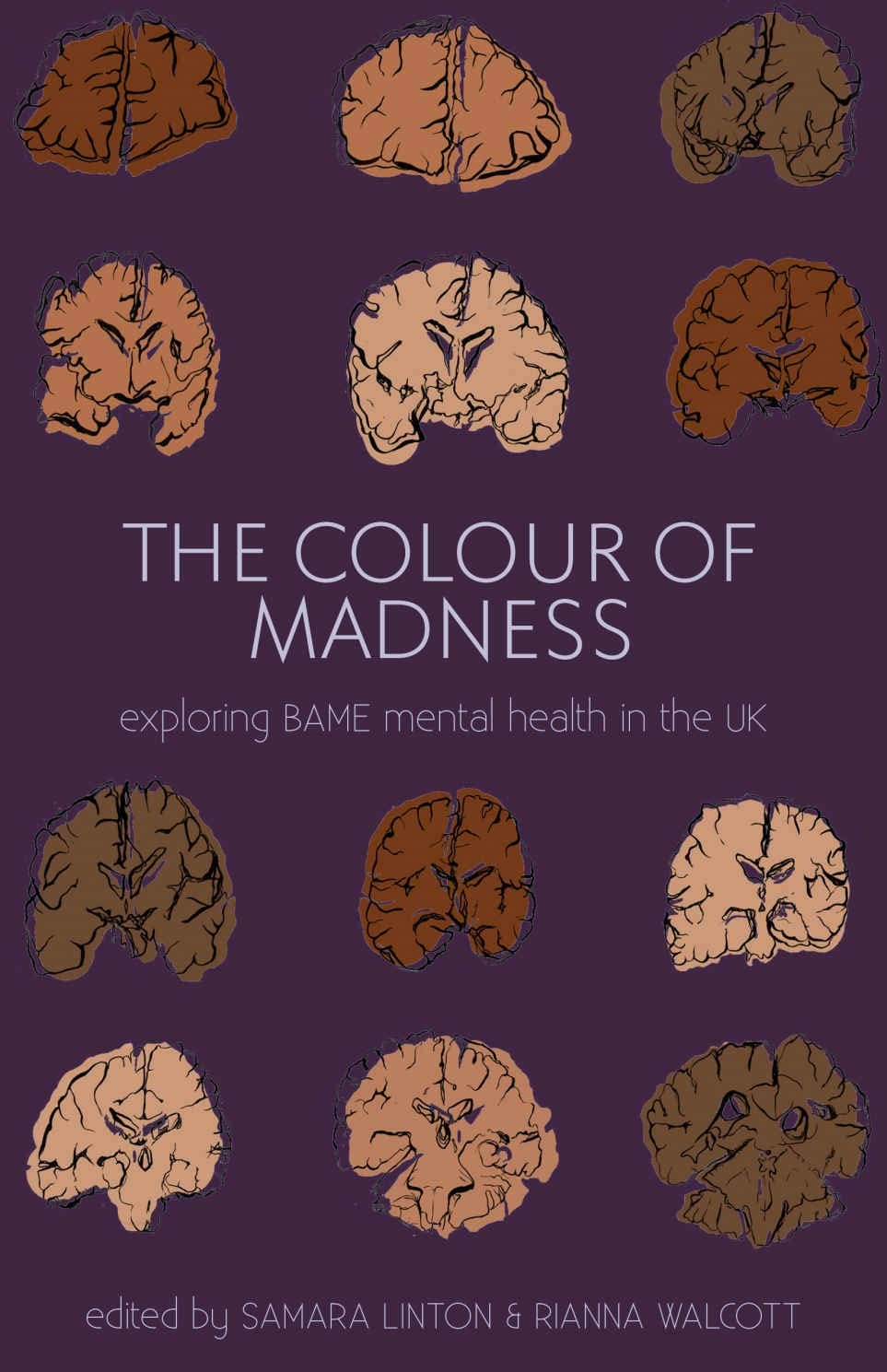

The data is damning. The ‘Writing The Future’ report into diversity in the literary world was published in 2015, and it made for stark reading. At the time, only 4% of guests at literary festivals were from a black, Asian, or minority ethnic (BAME) background. Malorie Blackman, author of the young adult novel series Noughts and Crosses and co-author of the report, lamented a decline in representation at these events. Rianna Walcott is the co-editor of The Colour Of Madness, a literary anthology about BAME mental health. She speaks of a notable absence of people of colour on discussion panels at literary events. Perhaps that’s unsurprising, considering that no books written by ethnic minorities were recommended for World Book Day, nor World Book Night. It seems that the ‘World’ does not extend beyond the West’s shores. In fairness, the event organisers complained that no publisher had put forward any books by writers of colour. No wonder, when BAME writers struggle to even start their literary careers, with 53% of this group without an agent, compared to 37% of white authors. Thus, the lack of diversity at literary festivals is really only the tip of the iceberg - the issue of diversity permeates every level of publishing.

So how do we respond to poor representation across the literary board? We can develop our own spaces. The Jhalak Prize for books by writers of colour offers such a platform for growth, offering a £1000 prize for the winner. The 2018 winner, Reni Eddo-Lodge, was shortlisted for other awards for her book, Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race. For those not fortunate enough to win the prize, there are other funding options. Nikesh Shukla, editor and contributor to The Good Immigrant, a collection of essays by Brits from immigrant communities, reached 204% of his funding target through the crowd-funding publisher, Unbound. Whether it’s recognition or resources, there is always the option of finding support through one’s communities.

However, prizes and crowd-funding carry their own problems. Nikesh Shukla fears that his “skin colour is being seen as a trend and not something that’s about a societal good”. Are these initiatives performative virtue-signalling by newly ‘woke’ corporations, or affirmative action? For comedienne Shappi Khorsandi, the idea of attaching a price to one’s skin colour led to her withdrawing her submission for the Jhalak Prize. Tokenism extends beyond concerns about perceived success. In the ‘Writing the Future’ report, several authors complained about being expected to write solely about their race, and specifically through a colonial lens. One author spoke of how, after refusing to write about the British Raj and racial deference of the governess-high maharajah dynamic, she resorted to approaching publishers in India. Her book was subsequently published and enjoyed success. This dubious notion of authenticity perpetuates stereotypes and restricts the inclusion of new voices. But, how do we increase diversity in an equitable manner that neither punishes white authors, nor fetishises BAME authors, and still ensures that our society remains a thriving community of literature?

The report’s recommendation sums it up best. The authors advocate for a greater recruitment drive, allowing people of colour to take up managerial positions. In doing so, the gatekeepers of the literary world would be more open to a diverse range of submissions. In the meantime, publishing bodies can undergo audits to identify cultural bias in their selection process. Beyond the recommendations, grants and interest-free loans can help working-class ethnic minorities to pursue literary careers. Penguin Random House offers 6-month internships to ethnic minority applicants, with Faber, Harper Collins, and Hachette following suit. While only 4% of children books have BAME characters, there is still hope for improvement. In the last 3 years, BAME staff have increased from 8% to 12% in publishing spaces.

Books can be a place of refuge, education, and solidarity. As the wise, ever-quotable James Baldwin said: “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read”. I can think of no better reason than that to bring more voices to the fore.

Review: The Colour of Madness: Exploring BAME Mental Health in the UK

The Colour Of Madness reminds us of one of the greatest powers of storytelling: giving a voice to the voiceless. Through anthology of verse, prose, and arts, this book is a rallying cry to the alienated and the alone. In the perfect storm of cultural stigma, mental health cuts, and rising racism and xenophobia, this collection of writings serves as welcome refuge for the vulnerable, and a guide for the practitioners who care for them. It comes as no surprise that it is being taken up by hospital wards and universities alike. Hopefully, this book will set a precedent for more writers to come forward, to describe their unique journey. Long overdue! - RM

The Colour of Madness - “This cannot be a conclusion. It is closer to a beginning.”

Rianna Walcott, 24, is currently studying a PhD in Digital Humanities at King’s College, London. Her work is on black digital identity formation across the diaspora. She is co-editor of The Colour Of Madness, a literary anthology about BAME mental health, alongside Dr Samara Linton. Here she chats to Books writer Rahul Mehta about her work.

Rahul Mehta: Where did the idea for The Colour of Madness come from?

Rianna Walcott: I was giving a talk in Edinburgh about mental health in the creative industry, and I was the only black woman on the panel. People seemed interested in my perspective, and I was approached by my future publisher. She suggested an anthology dedicated to BAME experiences of mental health.

It was definitely a BAME-led project: by us, for us, about us. My co-editor, Samara, had written as a journalist and an academic about black mental health, so we came in with both personal and formal experience on writing about mental health.

How did you plan and organise your vision?

We started with seeking funding. It was largely crowd-funded, with some funds coming from the publisher and creative arts funding. Samara and I handled the publicity in BAME spaces. Most of the press about our book was by women of colour in their spaces: Media Diversified, gal-dem, Black Ballad. We also featured in The Guardian, the Metro, and the BBC. But first of all, we wanted it to be in the hands of people of colour.

We had Facebook focus groups with over 100 individuals. Samara and I held brainstorming sessions about the book’s design and organised a large digital campaign to get submissions. We went beyond academic spaces: we went to service-user led charities, to find people of different backgrounds.

Were you informed by personal experiences of mental health?

Everyone on the team had some experience of mental health conditions, including depression and anxiety. This was not just an outside interest. In Samara’s case, she was able to see things as a patient AND a practitioner. The reason we make such a good partnership is because she has the medical background while I have the literary background (Rianna has an undergraduate and Masters degree in English Literature).

I’m impressed by the diversity of voices in the book.

The book reflects who is most comfortable talking about their mental health. For example, we had tons of submissions from black and Asian women, but barely any from black and Asian men. Male contributors tend to be practitioners (e.g. Asian doctors), or LGBT+. Most contributors were second or third generation immigrants.

But we have lots of people across different intersections. This highlights the diversity in spaces like the black community, e.g. the difference between those of African and Caribbean descent. It brings a lot of nuance that is missing from the conversation.

What was your biggest obstacle?

Money! We are all novices to this, and no one could have known the demand would be this high. We have had four print runs (unheard of in small print press). We have grown from our mistakes and learned a lot from the publishing process.

One funny thing is that a lot of white men submitted, some even pretending to be BAME. We’d respond by pointing them to our Patreon. If you’re not going to support us with coin, then what are you doing?

What’s your best memory?

People coming up to us at our events, in tears, because of how much it means to them. A contributor will be reading their piece at an event, and someone in the audience will begin to weep a little bit. This is the first time that someone has been able to say this out loud, the first time that someone has been seen. It’s been an incredible privilege to facilitate that.

You recently said: “This cannot be a conclusion. It is closer to a beginning.” What is your plan for the book?

We want to build on previous achievements. It’s on a university’s syllabus; someone even took it into Parliament! We want to see it everywhere, so that everyone understands that our experiences are unique. The book is the tip of the iceberg though, with only 58 perspectives. Imagine how many millions more there are!