The Picture of Dorian Gray

A decent, if somewhat humdrum production of Wilde’s novel

The Picture of Dorian Gray is one of Oscar Wilde’s best-known works, and certainly the most controversial. Published in 1890, it immediately attracted criticism for the hedonism and immorality promulgated in its pages, with Wilde accused of ‘offending public morals’. The story is of Dorian Gray, a beautiful young man who, influenced by the rich and sybaritic Lord Henry, comes to the pursuit of pleasure as the only important things in life. Rashly, he wishes that a painting of him at the peak of his youth would age, with he himself staying unchanged forever. His wish is fulfilled; despite his spiral into corruption, he remains young and beautiful, the portrait alone becoming the mirror of his wicked soul.

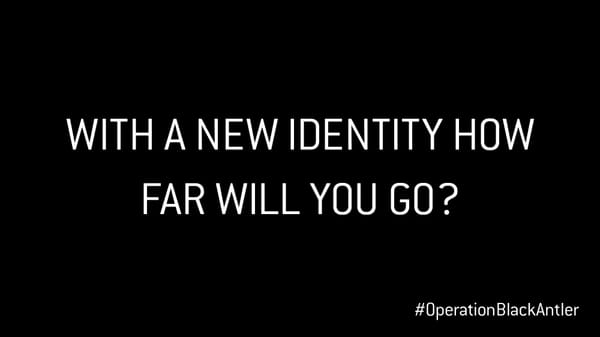

Tilted Wig Productions’ new adaptation, directed by Séan Aydon, makes a brave stab at capturing the complexity of Dorian Gray for the stage. While certainly a solid production, Aydon’s direction comes across as a bit too one-dimensional, missing out on the emotional subtleties and inner turmoil of Wilde’s original Dorian.

Perhaps this is also in part due to Gavin Fowler’s portrayal. Fowler never really seems to comfortably inhabit the character of Dorian. Excessively full of naivete in the beginning, he does a complete 360 into some sort of machisimo-fuelled sexual predator without so much as an interval between. With ‘good Dorian’ and ‘evil Dorian’ played rather like caricatures, there’s little explanation for why the ‘unspoilt young man’ suddenly turns into a cold-hearted, degenerate cad at what seems to be the drop of a hat.

Jonathan Wrather, on the other hand, makes for an excellent Lord Henry Wotton. Powerful and razor-sharp, he radiates the aura of one who is used to having his every desire fulfilled and with no compunctions about crushing others in the process. The seductive power of Wrather’s Lord Henry would corrupt anyone. It makes it all the more moving when he reappears in the last scenes as a broken man, who, for all his hedonistic convictions, has not found what he wanted in life.

Daniel Goode makes a good effort at playing Basil Hallward, the artist who is in love with Dorian and tries to save him from his downfall. It’s a very restrained and yearning depiction, with Hallward left dismayed and powerless as Dorian slips further into degeneracy. The only thing is that the relationship between the two seems entirely one-sided. You don’t really get the sense that Dorian is at all moved by Basil or that Basil ‘could have saved Dorian’ with his love – he just seems a bit of a side character who Dorian tires of once Lord Henry comes into the picture.

Also worth noting is Phoebe Pryce for her imperious, cool-as-a-cucumber portrayal of Lady Victoria Wotton, though her stage time was sadly limited.

All 19 scenes take place in Sarah Beaton’s delightfully eerie set – the high, cracked, paint-peeling walls of an artist’s studio appropriately capturing the themes of rot and decay. With no real set changes for any of the scenes, it gets a little static, but changes in lighting work well to convey the right atmosphere.

The production does suffer a little from a taste for melodrama, which rather detracts from the plot. Midway through, just to hammer home the point about Dorian’s descent into depravity, Lord Henry and Dorian go off to a Killing Kittens-esque sex orgy. The lights start flashing red, various masked, leather-clad people gyrate to thumping music and to top it all off, Lord Henry starts injecting heroin in the corner. I couldn’t help but giggle.

The titular picture is represented by a clear pane of plastic, which reappears as slightly cracked and opaque after Dorian’s misdeeds. I found this visually underwhelming – nowhere near vile and horrible enough to represent Dorian’s corrupt soul or to justify his horrified reaction at the end of the play. Dorian’s death, despite the flashing backlights and his melodramatically collapsing silhouette, ultimately falls short in actual dramatic impact.

Overall, a competent and visually pleasing production that doesn’t quite give us the wittiness and nuance of Wilde’s novel. Dare I say, the book is better than the play?

-3 stars