Scandals raises questions over Goldman Conduct

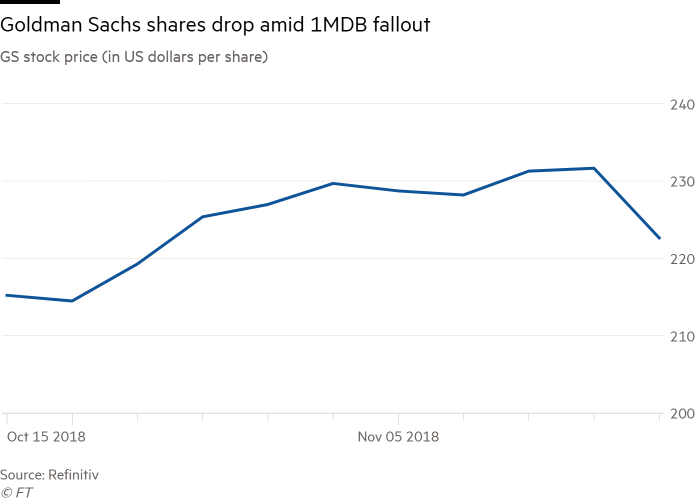

Back in 2010, Goldman Sachs was sued by the US Securities and Exchange Commission over allegations that it had misled clients over the mortgage backed securities it had sold. Internal Goldman emails surfaced showing how arrogant self-interest bankers had left their clients out in the cold to save their jobs and the cost to the Wall Street bank. However, Goldman soon recovered as the then chief executive Lloyd Blankfein paid $550m to settle the allegations, launching a top to bottom cultural review and spending 18 months visiting clients to reassure them that Goldman has received the message on ethics and will in the future put clients’ interests first. Despite this, at the beginning of the month the US Department of Justice revealed that two former senior Goldman bankers had been charged with money laundering in connection with the Malaysian state investment fund 1MDB, in what is alleged as one of the biggest frauds of all time. The purpose of the fund set up by Najib Razak, Malaysia’s Prime Minister in 2009, was to promote economic development. According to the Department of Justice, at least $3.5 billion was stolen from this fund and had found its way into the hands of Najib and many of his associates, to help in the purchase of a luxury apartment in Manhattan, a corporate jet, and ironically even helped finance the movie The Wolf of Wall Street. Goldman enters the picture 10 years ago, when it aimed to target Southeast Asia as part of its regional expansion. The bank built relationships with Malaysian tycoons and the government of Najib Razak. Consequently, state run 1MBD hired Goldman to work on $6.5bn in bond deals that reeled in $600m in fees, an unusually high rate for the service. Now Anwar Ibrahim, the likely future prime minister, has condemned Goldman Sachs’ role in the scandal as “disgusting” and has demanded that the bank should return significantly more than the $600m the banks were paid, due to the fact that “it’s a cost to the image of the country, it’s a cost to investments, and it’s now a burden shouldered by the government because of the complexity of so many of these so-called credible, renowned financial institutions”. Goldman refused to comment of Mr Anwar’s comments. Goldman had previously insisted it had no knowledge of the fraudulent activity, but it has now surfaced that Lloyd Blankfein met with Jho Low, the man at the heart of the scandal, at the banks New York headquarters during a meeting with the CEO of Aabar, an Abu Dhabi investment fund. It has emerged that the Abu Dhabi investment fund has filed a lawsuit in New York, claiming that Goldman bribed Mohammed al-Husseiny, chief executive of Aabar, to make them act against the funds interests as part of “a massive, international conspiracy to embezzle billions of dollars” from 1MBD. It is then no surprise that Goldman’s image has taken a significant hit in Southeast Asia, taking 17th spot for fees as of the start of November, as the Malaysian ruling coalition faces up to $10bn in debt repayments linked to the 1MBD scandal in time when it is grappling with a weak fiscal position, having revised the 2018 fiscal deficit from 2.8% to 3.7% in the latest budget issued in early November.

Goldman could perhaps recover if it was an isolated incident, however, on Wednesday South Korea’s financial regulator imposed a $6.7m fine on the bank for conducting a type of short selling that is banned in the country. The question Goldman must be asking themselves now is whether this new scandal threatens to undermine Goldman’s claims to be cleaner and more ethical, and whether its leaders have lost control of their empire amid their pursuit of growth.