Dark Pools: Evil place or a market place?

Dark pools. The words invoke an atmosphere of secrecy and evil, harkening back to myths of murky waters and ancient terrors that lurk within. Throw in the modern element of trading and most imagine clandestine deals involving dubious characters straight out of The Godfather. The reality is less intimidating.

Dark pools refer to non-public stock trading platforms where shares can be traded anonymously, in which details of the transaction and parties involved are not made public. They are only accessible to large institutional investors transacting large volumes of shares, allowing both parties to deal at desirable prices. To understand dark pools better, it is important to understand how the modern stock exchange functions.

From bustling coffee shops in the 17th century, where merchants and brokers haggled, the modern stock exchange has not veered from its main function: matching buyers and sellers. Companies listed on the stock exchange have shares being bought and sold regularly. Buyers and sellers submit orders through a broker and an electronic system matches orders to complete the transaction. Whilst stock exchanges have a minimum order size, known as a lot size, the sheer volume and breadth of participants from large hedge funds to individual investors create a spectrum of order sizes: from eye-watering millions to the lowly tens. It is hard to match orders of the same size and it becomes near impossible as the order size increases. Large orders are broken down into smaller chunks to be matched to sellers, and this happens over days.

For example, a seller submits a sell order of 10,000 shares in Company A. Should there not be a concurrent buy order for 10,000 shares of Company A, but instead ten buy orders to buy 1,000 shares each, the larger sell order will be broken down into ten blocks of 1,000 shares.

An important distinction with a stock exchange is price transparency; the total volume of shares in buy and sell orders are made public along with the bid and ask price (i.e. the highest price the buyers are buying or ‘bidding’ for a share and the lowest price the sellers are selling or ‘asking’ for a share are visible)

Price transparency can undermine the profitability of large deals. Participants dealing in large volumes of shares are often institutional investors, whose dealings are closely monitored as an indication of ‘smart money’ movement. It is assumed the people helming these institutions possess deep knowledge of businesses and valuable insights about future potential, giving them an edge over smaller investors. Therefore, public knowledge of large transactions can influence the share price of the companies involved as the wider market scrambles to profit alongside the institutions.

For instance, Fund B decides to sell 1,000,000 shares in Company A at $100.00/share on a regular stock exchange. The sell order is submitted, and the exchange begins to break down the sale into smaller chunks and find matching buyers. Traders and other market participants will notice an increase of sell orders for Company A, arriving at the logical conclusion that the ‘smart money’ have either; decided to take profit at the current share price or have knowledge of negative developments and are anticipating a drop. They would proceed to sell the stock as well, placing ‘pressure’ on the share price and causing it to drop further. This creates a ripple effect, as more market participants get wind of price movements and join in the selling. This effect, combined with the large order being broken down, results in orders being filled at ever decreasing prices, resulting in a lower net price for the entire order of 1,000,000 shares. If Fund B gets an average sale price of $95.00, 5% lower than intended, it represents a loss of $5,000,000 in potential profits. The effect would be similar for a Fund C buying 1,000,000 shares at $100.00/share, as buying pressure drives up share prices, resulting in a higher net price. Here is where a dark pool comes in handy for Funds B and C.

In the dark pool, the electronic system matches buyers to sellers anonymously just like a stock exchange. However, orders are secret, as participants do not know the price and size of transactions happening within. Crucially for public funds, knowledge of the transaction will only be released after the deal has happened, ensuring the ripple effect from the wider market will not affect the transaction. If two non-public companies, such as private equity firms, are involved in the transactions the wider market may never hear of the deal as they are not required to announce it. Trading fees in dark pools are also cheaper than exchanges. It is important to note: dark pools are not illegal, their operators are registered and regulated by financial authorities like a regular stock exchange. Dark pools were initially used by brokerages to ease the processing of large orders and have grown in popularity since the 1980s. Operators include banks such as Credit Suisse, Goldman Sachs, Citi, and Morgan Stanley and independent brokerages like ITG and LiquidNet. Even the London Stock Exchange operates dark pools: Cboe Europe and Turquoise Plato.

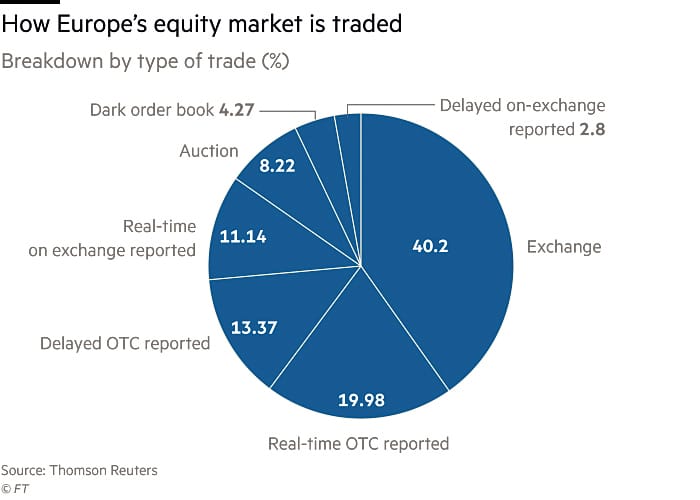

Due to the large orders, exchanges are concerned about the volume of trading being drawn away from regular exchanges, resulting in lesser fees for exchanges and lower activity for the wider market. According to Thomson Reuters, over 45% of daily traded volume in Europe occurs in off-exchange platforms like dark pools. With secretive deals the public is deprived of knowledge and are less empowered to make informed investment decisions, which breaks down the trust of public investors. Subject to less reliable prices and lower liquidity, it seems unfair for institutional investors to profit from a separate platform at the expense of the public.

The days of dark pool trading may be at an end with the introduction of the Mifid II (Markets in financial instruments derivative) regulations by the EU in early 2018. Meant to bring transparency and efficiency back to the European markets, this regulation seeks to drain Europe’s dark pools and force transactions back into the light. Under Mifid II, dark pools face a twin cap on the amount of trading that can be done. Just 4% of the total trading in any stock is allowed in a dark pool over a twelve month period. Simultaneously the trading of an individual stock across all dark pools is limited to 8% of the total volume in that stock. According to the Financial Times, upticks in the market share of some exchanges were noted in the week following the implementation of Mifid II.

However, as with any new rule, firms have found ways around them. An alternative less regulated trading platform sharing numerous features with dark pools, known as systematic internalisers (SI), are gaining popularity. Some 24 institutions have already adopted a SI status, including prominent banks, proprietary trading firms and market makers like Tower Research Capital, Citadel Securities and Virtu Financial.

While policy makers in the EU have made clear their desire to clamp down on dark pools, there is no intention to eliminate them, accepting the need for institutions to transact without shifting the market price. There are exceptions for unlimited trading in dark pools for large orders. SIs with cheaper fees and lower standards for quote sizes and trade reporting will fill gaps not big enough to match the EU’s large order exemption rule, but large enough to affect market prices. With the UK set to leave the EU the matter of Mifid’s enforcement arises. Policy makers have jumped into the deep end of regulating dark pools.