Are Uber’s bankers getting cold feet?

The ride haling app has lowered its expectations from a rumoured IPO valuation of around $100 billion to between $80-90 billion. This would still be the largest public offering from Silicon Valley since Facebook, with the company pitching an initial price range of $44 to $55, even as many other highly valued tech companies such as Slack enter the public domain. Many believe this conservative pricing is a result of the underwhelming stock performance of competitor Lyft, which is currently trading 20% below its issue price after it went public earlier this year. Lyft is in fact threatening a lawsuit against Morgan Stanley (one of the underwriters of the IPO) after its alleged role in helping market certain products that would help pre-IPO investors bet against the stock which certain traders believe caused the early drop in share price.

A Morgan Stanley spokeswoman told CNBC “the firm did not market or execute, directly or indirectly, a sale, short sale, hedge, swap or transfer of risk or value associated with Lyft stock for any Lyft shareholder identified by the company or otherwise known to us to be the subject of a Lyft lock-up agreement.”. Interestingly, Morgan Stanley are lead underwriters of the Uber initial public offering, in conjunction with Goldman Sachs and Bank of America. This raises that eternal question; do banks represent the client or the investors and how do they manage these conflicts of interest? Uber has already warned that existing shareholders might enter into hedging deals that would hurt its share price. Furthermore, in almost all respects, Uber is in a worse financial position then Lyft. It is growing at a much slower rate, with Uber’s Take Rate, the percentage of gross bookings it captures as core platform adjusted net revenue, has been steadily in decline throughout 2018. Uber has also declining market share with no real competitive advantage that will allow it to earn a sustainably high return on invested capital (a key metric investor use when investing in a company). Despite this Uber’s IPO documents show how it has been spending heavily, burning through $2.1bn in cash in 2018, maintain market share. Its not surprising that there are serious questions about Ubers profitability.

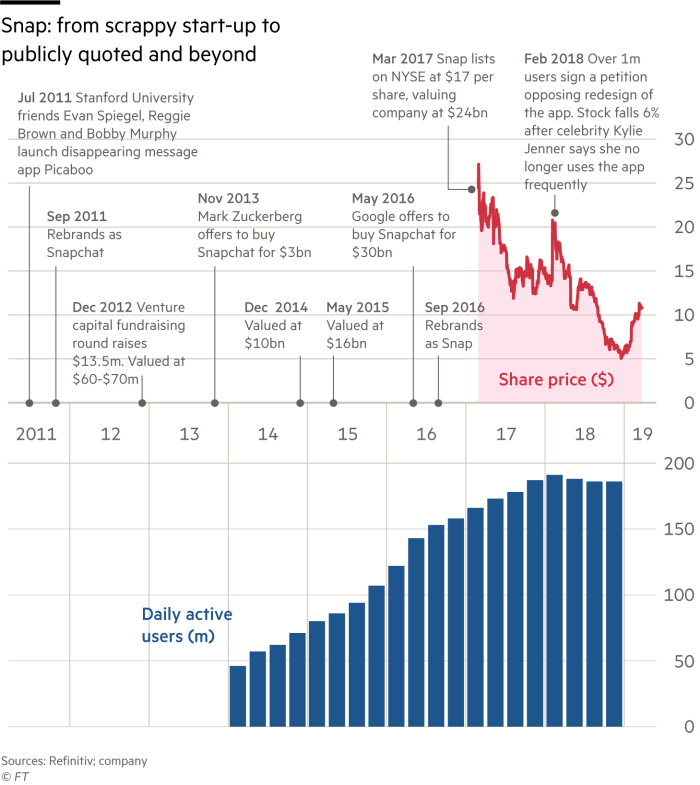

Another comparative example could be Snap, who went public for $24 billion in early 2017, listing on the New York Stock Exchange at $17 per share. Now two years later the shares trade at roughly 30% below the listing price. One might ask then why Uber wants an IPO at all, when there appears to be clear evidence similar firms have failed to raise predicted funds in the public market. It could be because chief executive Dara Khosrowshahi, and four other top executives have options for nearly 4m shares, a strong incentive for them to move quickly into an IPO.

It may also be that they have exhausted private investment sources after Softbank’s vision fund injected $7.7bn into Uber in January 2018 to become the largest shareholder. However, what is interesting is that Alphabet and Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund are not selling any of their shares in the IPO. This tells us they still believe there is potential for future growth, and that they are willing to deploy capital to maintain their investment if necessary. This provides Uber was a unique cushion, an advantage for smaller, newer investors.

Uber has also remained very ambiguous about its key metrics. Analysts use these to build models and forecast future growth of a company. For example, the company has decided not to disclose what the breakdown is of passenger rides and restaurant deliveries is. Consequently, this makes investors sceptical over whether Uber can be accurately valuated. Despite all of these factors, Bloomberg was reporting as this article was written that the Uber IPO was oversubscribed by day two of the roadshow, with meetings in London on Monday and New York on Tuesday. Only time will tell how the initial public offering goes this month but observers will be watching this bellweather offering carefully.